Fred Cornwell’s War

Fred Cornwell’s

War

Jane Maureen Cornwell Barder

May 2016

|

CORNWELL FREDERICK CHARLES 6105756 PLACE: JERUSALEM APRIL 1946 PRESENT RANK: P/A/SGT REGT: R SIGNALS SERVICE TRADE: CIPHER OP (HIGH GRADE) MILITARY CONDUCT: EXEMPLARY A meticulous and conscientious worker, this NCO can always be relied upon to perform his duties thoroughly and efficiently. He is a good all-rounder and generally popular. He has occupied a position of trust and responsibility and has given complete satisfaction. PALESTINE COMMAND SIGNALS |

FRED CORNWELL’S WAR

[nb: An early version of this paper, published on 12 August 2016, lacked most of its illustrations. These were restored by 8:30 pm BST on the same day. If you accessed the paper before that time, please re-load it and look at the rest of the pictures and illustrations. Apologies! — Brian]

This testimonial to a popular, conscientious and exemplary sergeant marks the end of my father’s military service in the Middle East. All that remained now for Fred Cornwell was an overnight journey to Port Said for embarkation on a boat to Toulon, a train across France and a cross-channel boat to UK. Next, a stop at Royal Corps of Signals in Caversham, Reading, to be issued with his Soldier’s Release Book, stamped on 23 April 1946, and a Third Class railway warrant from Woking to Waterloo. A surviving letter to his wife, my mother, shows that he had left Jerusalem at 6pm on 12th April. That letter, written on 12 April, and saying that his kit was packed and he was ready to leave, probably arrived after him but we three, my mother, my younger sister Sally and I, had somehow been told that he was due home some time soon. It was a belated end to a long separation and, for us, an overdue end to the war.

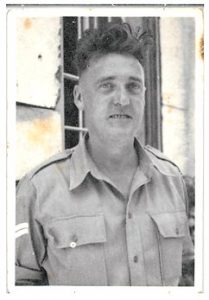

Fred’s Ministry of Defence Service File records that his ‘Total Reckonable Service for Gratuity’ was 4 years 106 days, and that from mid-1942 until  mid-1946, he served successively in Egypt, Palestine, Syria and then Palestine again. His enlistment paper in January 1942 states his ‘Period of Engagement’ as ‘D of W’ (Duration of War) but he soldiered on for nearly a year longer than the duration. When he was demobbed on 23 April 1946 he had accumulated 103 days’ leave. So his army service, including this leave, lasted from 8 January 1942 until 4 August 1946.

mid-1946, he served successively in Egypt, Palestine, Syria and then Palestine again. His enlistment paper in January 1942 states his ‘Period of Engagement’ as ‘D of W’ (Duration of War) but he soldiered on for nearly a year longer than the duration. When he was demobbed on 23 April 1946 he had accumulated 103 days’ leave. So his army service, including this leave, lasted from 8 January 1942 until 4 August 1946.

From the meticulous but often mystifying entries over three short pages of his service record, I have tried to reconstruct some of what he experienced during the Middle East years, as well as during the five months from January enlistment to May embarkation. I marvel that these careful paper, pen-and-ink records were being made in the heat of war by men whose families were as worried about them as we were worried about our husband and father and that, 75 years later, they can be found and posted to his family.

I am attaching to this paper a list of sources and references that I consulted in writing this account. I also had lots of talks with Sally, whose memories of our father’s departure and return are much clearer than mine.

PRE-CALL-UP

When Fred received his calling up papers in January 1942 our family had already experienced some of the depredations of the war, which by then had lasted for over two years. After the Battle of Britain in late summer 1940, when impossibly young and brave RAF airmen, with support from the Free Poles, Free Czechs and Canadians, with a few others, drove back the Luftwaffe from our skies, came the Blitz. It started on 7 September 1940 and lasted with nightly bombings until 16 May 1941: in October 1940 we were among its victims. In the middle of the night, our house, 23 Winslade Road in Brixton, was badly damaged by bombs which flattened other houses in the road. Fortunately, the four of us were in our Anderson shelter [[1]] in the garden when the roof fell in, the windows shattered and walls buckled. We were hauled out by ARP wardens [[2]] who noticed that we hadn’t been checked off the list of residents in the road. We then set off on a dramatic walk to his mother’s house in Coldharbour Lane. Sally was only four years old so our father carried her in his arms and I, aged 6, walked along holding our mother’s hand. We remember the sky full of searchlight beams and aeroplanes, the sounds of the ‘screaming bombs’, the four ack-ack guns on Clapham Common and smaller guns on Brixton Town Hall, emergency vehicles racing along Acre Lane, police and ARP whistles and shouts. We were alive but homeless.

At around the same time our maternal grandparents’ house in Figges Marsh, Mitcham was demolished by a landmine. It was during the day and they were out, so they too were alive and homeless. 23 Winslade Road was eventually made habitable again for us to move back in, probably towards the end of 1942, and our grandparents then came to live with us. Sally and I remember the places where we stayed meanwhile but we can’t re-construct the timings. In October 1940 we’re sure we stayed immediately with our maternal Uncle Arthur’s family in Mitcham where we slept on the hall floor. (It was believed that short of a shelter the safest place was under the stairs, but there wasn’t room for all of us in the cupboard there.)

We soon found ourselves evacuated to Accrington, a mill town in Lancashire. Our grandparents came too and so did Arthur’s wife and our two cousins. Each of the three separate family groups was billeted in one room of small terraced houses in neighbouring streets. We were in Water Street, apparently the street where Jeanette Winterson lived with her adoptive family, and we probably had just as miserable a time as she did. Sally remembers that our father came to see us in Accrington at Christmas 1940. But our mother was saving to get us back to London as soon as she could: she preferred London even with bombs. We must have still been there at the end of April or early May because we remember a beautiful glade of bluebells in Peel Park, and that is when they are in flower. The grandparents and aunt and cousins also returned to London and we think we must have gone back to Mitcham. Our grandparents had been rehoused in a requisitioned maisonette in Heaton Road Mitcham. (Houses left vacant for whatever reason were taken over (‘requisitioned’) by the government and rented to those made homeless by bombing.) Sally remembers being taken from our aunt’s house to sleep on a truckle bed in Heaton Road when she developed scarlet fever, and I remember seeing her wrapped in a red blanket and taken by ambulance from Heaton Road to one of the Fever Hospitals which existed in those days. We were then given refuge by our mother’s cousin who lived in a council house in Shooter’s Hill Road in Blackheath. We shared her Anderson shelter with her five children until we also were allocated a requisitioned property. This was the ground floor of a house, 25 Winterwell Road, the next road to Winslade Road. This move, almost back to home, must have been some time towards the end of 1941. Sally and I then started school properly at Lyham Road elementary school, where we stepped over the camp beds of the Auxiliary Fire Service on our way upstairs to the classrooms. Schools in London had been closed at on the outbreak of war and taken over by civil defence forces. But most were now re-opened and sharing their sites if necessary.

While his wife and children were moving around, Fred had been continuing to work on one of the family stalls in Brixton Market, no doubt living with his mother in Coldharbour Lane. Some categories of those involved in food distribution were listed as in reserved occupations, which was why he hadn’t been called up earlier. But by 1942 extra manpower was vitally needed in the Middle East where Rommel and the Afrika Corps were holding the Eighth Army at bay, as well as for other battlefronts further east. The Japanese were overrunning Asia, threatening India and Australia, Singapore was to fall in February 1942, and the Germans were on the counter-offensive against the Soviets. The time had come to call in the Lambeth Boys.

JOINING UP

The address on Fred’s enlistment form, dated 22 January, was 25 Winterwell Road, our requisitioned flat: we had had a few months together as a family again. Sally has a vivid memory of the day he left. She describes how he had a bowl of water and a mirror on the dining room table. (Our downstairs half of number 25 didn’t have a bathroom; there was an outside lavatory and a tin bath hung on a hook outside the back door which our mother used to bring in, put on the floor and fill with hot water for baths.) Sally says that she and I were sitting together on the couch, watching him shave and talking to him before he left. I have absolutely no memory of the day or the feelings I must have had. Sally also says that he came to see us again before he left for destinations unknown. She is obviously right because servicemen always did get embarkation leave, but again I don’t remember.

During the years Fred was away we corresponded to the extent that we could, on specified forms and aerogrammes and aerographs of certain sizes, censored and with long delays. Only two or three of his letters and cards have survived, and he couldn’t be very forthcoming in them anyway. We do have a few photographs. It seems that in some areas soldiers were allowed to send one free parcel a month. It was always exciting to receive a letter but our mother would always say: at least he was alive when he wrote that. Once back home in 1946, like so many of his contemporaries, he never talked about his experiences, and I believe that he kept up with only one friend, Bill Sergeant, from army days. He didn’t keep a diary, so what we learn from his service file and the keys it gives to public records is all we can know about those years of absence. Fortunately, other soldiers kept diaries and some of them are now held in the Imperial War Museum. I have read the diaries of two soldiers, JR Stokes and HA Wilson [[3]], whose army careers were similar to Fred Cornwell’s. Both were raw recruits who, after brief training, spent time in the Middle East at some of the places where Fred served and both describe their transfer and training as cipher operators. Much of what they describe would clearly have been what Fred lived.

On enlistment Fred was posted to 1/6 Battalion, 131 Brigade of the Queen’s Royal Regiment (West Surrey) [[4]]. Formed in Putney in 1661, this was historically the Regiment of South London and neighbouring Home Counties, some units known as The Bermondsey Boys. JR Stokes from Woking was also assigned to the Queen’s Royal Regiment when he was called up in March 1940, and he did his initial training at the historic Regimental HQ barracks in Kingston. In 1942 when Fred Cornwell joined the Regiment, 131 Brigade, Queen’s was serving as part of the Dover Garrison which since April 1941 had been under the command of General Montgomery in its task of defending the nation against imminent invasion. He is said to have instituted a regime of continuous training and insisted on high levels of physical fitness for both officers and other ranks throughout his command. The 1/6 Battalion was based at Faversham, so Fred may have been sent to Faversham rather than Kingston for training. No doubt the routine, whether in Kingston or Faversham, would have been the same. Stokes describes his arrival in Kingston, one of a group of recruits who, still in civilian clothes, were given coffin-shaped linen bags and sent to the stables to fill them with straw. This was their mattress. A smaller straw-filled bag was a pillow and the beds were three wooden planks on a trestle. They were given three blankets but no sheets. He said it was years before he experienced a sheet again. They were supplied with a denim working uniform and a serge battle dress, taught how to march, salute and handle a rifle and received their Tetanus and TAB vaccines. Stokes then had a week’s embarkation leave, starting on 14 April, which was followed by war games and long marches in Richmond Park before his brigade travelled to Liverpool to set sail for Egypt.

THE VOYAGE OUT

According to a history of the Queen’s Royal Regiment in the Middle East, the 44th Division, which included Fred’s 131 Brigade, was warned in March 1942 to be mobilised for overseas service by 15 May. So it may have been in March that Fred came home on embarkation leave, going back, as Stokes had done, to war games and long runs before leaving the UK. King George VI visited the Division on 14 May 1942 and the 131 Brigade embarked at Gourock in the Clyde estuary near Glasgow ten days later, on the 24th. The Queen’s history describes a large convoy of 23 ships, a few passenger liners, eight occupied by 44 Division, and various other troopships. They were escorted for the perilous journey by the battleship HMS Nelson, an aircraft carrier and a number of destroyers. The United States had entered the war after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbour a few months previously and Winston Churchill had persuaded President Roosevelt to make shipping available to help with the transport of two divisions.

From Fred’s Service file

Thus 1/5 battalion of 131 Brigade, together with the 133 Field Ambulance and a few members of the Pioneer Corps, about 1,200 troops in all, was embarked on a US ship, the Christobal, on its second troopship duty after being requisitioned from the Panama Railroad Co. on 11 January 1942. There was a rocky start to relations between US and UK officers and in turn with the ship’s officers and the Captain. The Queen’s account maintains that the situation was brought under control by the Commanding Officer of 1/5 Battalion which comprised the bulk of the troops on board. Peaceable relations however probably didn’t bring much comfort to soldiers experiencing the inevitable squalor of wartime troopships, particularly since the Christobal was ‘dry’, like all US ships.

Fred’s 1/6 Battalion and the 1/7 embarked on the Strathallan, a P&O liner launched in 1938 to service the Sydney route and requisitioned by the UK Ministry of Shipping in February 1940. She was the biggest of the P&O fleet, built to accommodate 1,011 passengers, 448 in first class and 563 in tourist+ [steerage?]. On this voyage she carried 5,000 troops but at least she was ‘wet’: beer and sometimes a tot of rum were issued. The Queen’s history describes the journey in a very bland way:

After the rough weather had abated, the convoy sailed into a fog which persisted for a day or so, which was no doubt extremely useful in providing a screen from prying aircraft or passing U-boats. When the fog lifted the convoy sailed into some excellent weather…. although at times, it became extremely hot.

An account in the BBC Peoples’ War series, by Jim Gormley a 20-year-old RAF recruit who sailed on the Strathallan later in 1942, paints a more vivid picture of the conditions endured on the Strathallan by him and no doubt by Fred [[5]].

We were sent to “G” Deck well below the water line. There must have been …A…B…C…D…E..F decks above us and there was some below us. I slung my hammock next to a watertight door (WTD), which led to the engine room, which gives an idea how far we were in the bowels of the ship. We were packed like sardines. Bulkheads had been removed to make open spaces to get more troops in. There were rows and rows of tables and benches of the very basic type. Each table had 24 soldiers. We had to eat, sleep and have recreation in that area. We had a duty roster to get up on deck for fresh air and exercise….It was like being at a Rangers and Celtic match on cup final day. We were shoulder to shoulder above and below decks. The humidity and smell was appalling. We were ordered to remain in our uniforms at all times in case of emergency even as we slept but the heat was such dozens of the troops disobeyed the order. I kept my uniform on at all times. I was a bit of a rebel and didn’t like to follow the leader…. Mealtimes were an ordeal. We had a duty roster of bringing meals in 24 canisters from the galleys to the table. Each man had his ‘Dixie’ and a fork knife and spoon. They were like diamonds. Woe betides if they were lost. The ‘Dixie’ was a metal container, which had two parts that closed together. One half was for main course the other soup or desert when we got it of course. Improvisation was the then buzzword…. We would queue for an hour at a time all-staggering against each other as the ship pitched and rolled. Carrying back the 24 canisters to the table was a nightmare. Most of the troops were seasick with decks covered in vomit. We were slipping, sliding, sometimes falling with the canisters going in all directions. I was never sick and proving that every cloud has a silver lining, there was always extra food available, as many never ate for days…. The weather never let up until, reaching a crescendo as we crossed the Bay of Biscay, sometimes the ship going into 45% angled rolls. It was a nightmare voyage. As we sailed into the Mediterranean Sea at last the weather abated.

I remember hearing from our mother that Fred had slept in a hammock which was somehow slung above another hammock.

A very different view of conditions on the Strathallan is contributed to BBC People’s War by Captain KD Kettle MC [[6]]. As a young officer he travelled on the same date as Fred:

There were some eighty Queen Alexander’s nurses aboard, and those of us officers who enjoyed their company, in the main dining room, dressed up (KD mess uniforms) for the six-course dinner every night, when not on submarine watch.

Kettle, and another account of that particular voyage, give 30 May as the departure date whereas the Regimental history dates it as 24 May. Possibly the men were loaded on 24th and then waited six days for their turn to sail out in that large convoy.

The first stopping point for the convoys, after about 14 days of sailing, was Freetown, Sierra Leone. The ships stayed there for several days but although some were able to send cables home no one was allowed to land. On Fred’s voyage HMS Nelson’s sister ship, HMS Rodney, joined them there for the onward journey, but the aircraft carrier had already been dispatched elsewhere. Their ultimate destination was still a secret. A fortnight later, Christobal with half the convoy arrived in Durban and Strathallan with the remaining ships put in to Cape Town. The Queen’s history relates that everyone was allowed ashore in both places and feted by the populations. Route marches were organised each day and the marching columns were showered with oranges and other presents. Strathallan spent three days in Cape Town but then sailed into enormous waves causing the ship to roll alarmingly. The convoy reunited at sea and sailed into Aden on 16 July by which time it was obvious that 44 Division was destined for Cairo.

As the Queen’s history remarks, with a certain amount of understatement: “The battle in the Western Desert had not gone too well.” Tobruk had surrendered on 21 June with 20,00 prisoners taken, and the remainder of the Eighth Army was in full retreat. On 21 July, after 58 days at sea, 131 Brigade disembarked at Port Suez and entrained to Khataba Camp, 60 miles east of Cairo on the edge of the desert. The following weeks were spent in training for desert warfare and on 14 August the order came for 44th Division to join the Eighth Army immediately. In his 1940 diary, JR Stokes described the conditions he found when he, like Fred Cornwell in 1942, landed in the Suez Canal Zone. Stokes was taken to a huge camp at Geneifa and found his regiment living in trenches cut in hard sand, one hot meal a day, the rest of the time bully beef and hard biscuits, shortage of water, washing in sea, hot sun by day, cold at night, the worst being dust and flies, long marches to make them fit. When Stokes’s brigade left the training camp to take part in the battle of Sidi Birani in December 1940, they marched out in khaki shirts and shorts, with steel helmets, gas masks, ammunition and a pint of water. This might describe how Fred Cornwell left Khataba after 24 days of desert training to join the 8th Army on 14 August 1942. Officer Kettle leaves this account of his time at Khataba where he, like Fred, had gone from the Strathallan:

We experience our first sandstorm for some 24 hours, strong winds, oppressive heat, sand everywhere. At least the swarms of flies that pestered us day and night are temporarily laid low. We sit it out in our tents or bivouacs, and stay under cover, all part of making us “Desert Worthy”. The camp was not comfortable but the training was good.

The chances are that conditions in the camp, like those on board, were rather different for officers.

EIGHTH ARMY

The summons for the 44th Division to join the 8th Army immediately had come from General Montgomery who had arrived in Egypt only two days previously to take up his post as GOC Eighth Army. Winston Churchill had arrived in Cairo on 3 August, visiting HQ Middle East Command on his way to meeting Stalin in Moscow, and had found 8th Army troops ‘brave but baffled’ as they awaited an expected attack by Rommel and the Afrika Corps following the defeat at Tobruk and elsewhere. Churchill had removed General Auchinleck from his joint roles as C-in-C Middle East and GOC Eighth Army, replacing him by General Alexander as C-in-C and by General Gott as GOC Eighth Army. However, Gott was shot down by German fighter planes on his way to take up his position and General Montgomery was summoned from the UK to take his place, arriving on 12 August. Montgomery immediately scrapped an existing plan which involved a ‘feint’ to draw Rommel onto Alma Halfa Ridge and then attack him from the north, thereby abandoning the Ridge. Montgomery decided to hold the Ridge and hope that Rommel would exhaust his forces before attacking El Alamein. But this required extra infantry to defend the Ridge. The newly arrived 44th Division, the only infantry available, had not yet completed their training but, as already described, they had served under Montgomery’s command in the South Coast defences and he considered that they would be ‘quite able to demonstrate the traditional tenacity of British infantry in defence’. Two days later 131 and 133 brigades arrived on Alma Halfa Ridge. 1/6 battalion was set to cover the defence of the airfields in the area and the western gaps in the minefields and, like other battalions, began the hard work, in high temperatures and on the rocky ground, of digging in. According to the Queen’s history they were given great encouragement by a visit from Winston Churchill on 20 August. On 30 August Montgomery’s planned battle of Alma Halfa began. The first phase finished on 6 September. 131 Queen’s didn’t come in contact with the enemy: they were dive- bombed and shelled, but they were well dug in and took no casualties. But Fred was not there for the battle.

HOSPITALS

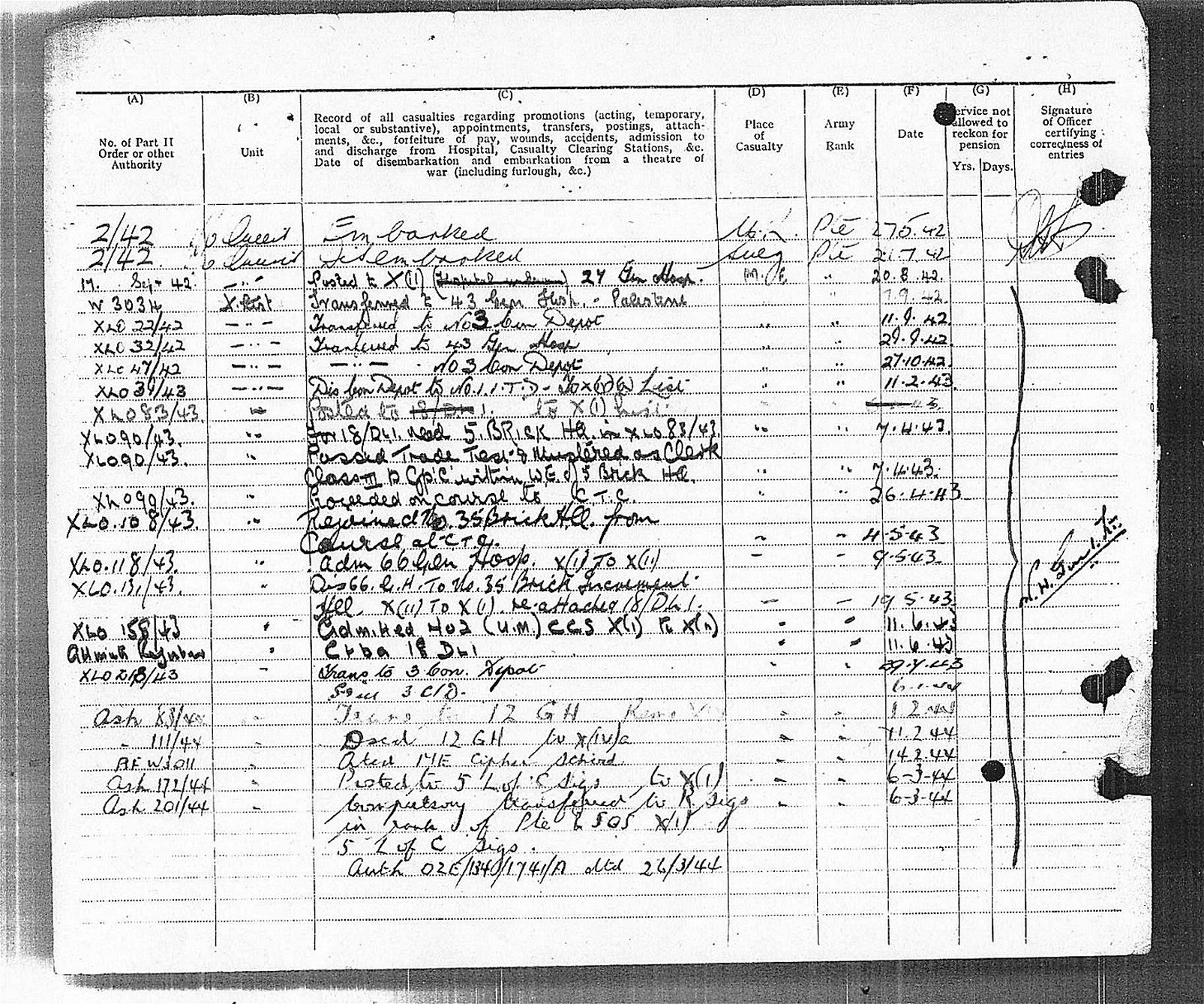

Churchill’s 20 August visit to the 1/6 was a momentous day for Fred. On that day, his file lists him as ‘posted’ from the Ridge to 27 General Hospital which the Scarlet Finders website [[7]] shows as being in Geneifa, the large military base in the Suez Canal Zone where JR Stokes had had his first experience of Egypt. Transfer to a hospital on the eve of battle, rather than being treated in the Regimental Aid Post, suggests a pretty serious condition. Eighteen days later, on 7 September, the file shows him ‘transferred’ to 43 General Hospital, Palestine, which Scarlet Finders identifies as being in Jerusalem: he was there for four days before being transferred to number 3 convalescent depot [[8]]. Again according to Scarlet Finders, this convalescent depot was in Nathanya, Palestine, now in Israel and known as Netanya. In a 2004 history of British Mandated Palestine, Rosa El-Eini mentions that that when Nathanya was a British Army convalescent depot during the war, the patients used to raise ducks, turkeys and pigs. But 18 days in the depot did not cure this patient and on 29 September the file records his transfer back to 43 General Hospital, Jerusalem, where he was kept for another month. On 27 October he was transferred back to the Nathanya Number 3 convalescent depot where he remained until 11 February 1943. By then he had been ill and out of action for six months. This must have been the time when he had the diphtheria and dysentery we knew about as children.

Our mother had obviously been informed of this at some stage. I recall occasional talk of letters from the Colonel’s wife who seems to have had the role once filled by wives of Heads of Chancery in the Diplomatic Service – a sort of unpaid welfare officer. I think it was such a letter that told us of the Regiment’s embarkation in 1942 and she might have written when Fred was so ill. Diphtheria was a killer: a vaccine had been introduced in recent years but not for those of his generation. It’s miraculous, and perhaps a tribute to careful nursing, that he survived. The weeks of transfers back and forth between hospitals and convalescent home suggest a quite common recurrence of the diphtheria, but more likely recurrent amoebic or bacterial dysentery: none of the anti-toxins or antibiotics available for treatment today had been invented or discovered in the 1940s. Florence Nightingale-type nursing was often the only way of keeping people alive. My assumptions that he had fought at the battles of Tobruk and Alamein, based on nothing but the fact that he had indeed been in the Eighth Army during the relevant years, have not been borne out. He was fighting his own battles during those years. And the health battle went on until his last hospital admissions in August 1944. The wonder is that he survived and that he came home and buckled down to all those years working on the stall, come wind, come rain. I also find it amazing that the Army’s duty of care to a soldier was honoured in such a faithful fashion. At the height of vital battles he, and presumably others, was ferried to and fro from hospital to hospital, he was nursed back to life and every move was so meticulously recorded.

18/DURHAM LIGHT INFANTRY & 35 BEACH BRICK

On 11 February 1943 after his three months at Nathanaya Convalescent Depot, Fred was discharged to ITD (Individual Training Directorate). His status was now ‘x (iv)’ [[9]], signifying that he was available to be posted to a unit: his Queen’s posting had lapsed after more than 21 days in hospital. For the last six months he had been on the x (ii) list, in effect the sick list. The ITD had the task of deciding his next posting, and later that day he was posted to the 18th Durham Light Infantry [[10]] and his status was changed to x (i), meaning that he had been posted to fill a vacancy in an authorised WE (War Establishment). This posting was clarified by two file entries on 7 April 1943. The first read ‘For 18/DLI read 5 Brick HQ’. and the second: Passed Trade Test and mustered as Clerk Grade III within the WE of 5 Brick HQ’. Beach Bricks [[11]] were an innovation which followed Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of French North Africa in November 1942 and the first active involvement of US troops. It was apparent that huge troop landings of this kind needed huge support back up, controlling movements between landing craft and inland assembly areas, moving stores from crafts to beach, creating the assembly areas, evacuating casualties, providing a beach signal organisation, and overall administration. In the UK, Beach Groups began to train in Scotland; in the Middle East equivalent organisations called Beach Bricks began to train in Kabrit, Egypt. An RAF website [[12]] describes the composition of Beach Bricks. The core of each Brick was an infantry battalion. Along with the R.N. Beach Party and specialised units from the R.E., R.A.S.C., R.A.O.C, REME, R.A.M.C., plus pioneers, anti-aircraft gunners, signals personnel and an R.A.F. component, this took the total number of men in each Brick towards 3,000. The 18th Battalion DLI was the infantry core of 35 Beach Brick. I think the initial reference to 5 Beach Brick must have been a rare mistake because I can’t find any other reference to 5 Beach Brick in the Middle East.

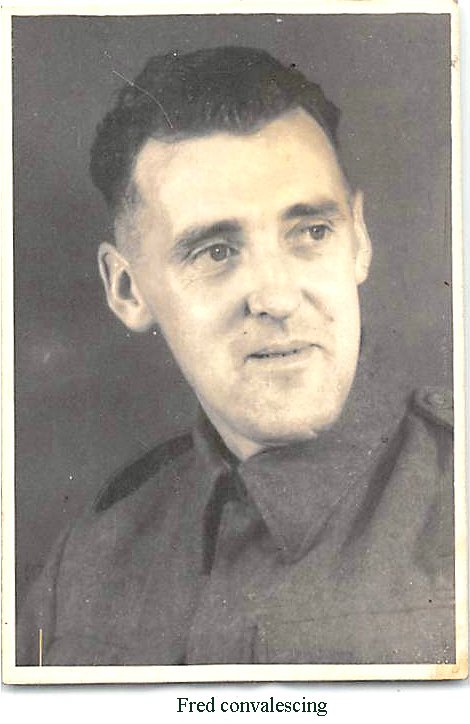

Apparently the 18th battalion DLI, Fred’s new regiment, included a number of men from other northern regiments: Colonel Ralston, the CO was from a Highland regiment, Major Cameron, the adjutant, came from the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders. This probably explains the origin of a treasured photograph of our father in a kilt (above). We received that when he had been transferred to the Duham Light Infantry and Sally and I assumed that this was his new uniform. He must have borrowed it from one of his new comrades.

Apparently the 18th battalion DLI, Fred’s new regiment, included a number of men from other northern regiments: Colonel Ralston, the CO was from a Highland regiment, Major Cameron, the adjutant, came from the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders. This probably explains the origin of a treasured photograph of our father in a kilt (above). We received that when he had been transferred to the Duham Light Infantry and Sally and I assumed that this was his new uniform. He must have borrowed it from one of his new comrades.

We understood as children that it was because Fred was suffering from diphtheria and dysentery that he was left behind when the Queen’s moved on to invade Italy, but in fact on 26 April 1943 Fred, apparently fully recovered, found himself beginning to train for the Italian invasion. He was training not with 1/6 Queen’s, which in the event played a large part in leading the breakout and advancing across the Plain of Naples, but alongside 18/Durham Light Infantry, core of a supporting Beach Brick. His file entry for that day reads ‘proceeded on course to CTC’ (Combined Training Centre). A supplement to the London Gazette of 13 November 1946 describes how in 1943, Middle East Command provided and staffed training establishments necessary for future Eighth Army warfare such as the imminent invasion of Sicily, followed by mainland Italy: and that this included training Beach Bricks personnel. An existing Combined Training Centre at Kabrit, in the Gulf of Suez, was enlarged and its remit expanded and accelerated to include 4 Beach Bricks who were all trained alongside the assault troops they would be accompanying and supporting on landings. John Grehan and Martin Mace in a 2015 history of Middle East operations [[13]] describe how the vigorous training at Kabrit included 14 days at a Mountain Warfare centre in addition to assault training, physical fitness exercises and lectures. Two Durham Light Infantry Majors, Lewis and English, in a history of the 8/DLI ’39 – ’45 [[14]], and George Iceton in a long Imperial War Museum audio interview about his service from private to sergeant in 6/DLI [[15]], give some picture of the training regime. Iceton describes an unusual start to the days with a run up a mountain before the regular ‘morning gunfire’ (army name for essential morning cup of tea). The Majors also mention the morning run up the escarpment which kept the Medical Officers busy with injuries, some very serious, during the climb. One man from HQ fell to his death, they report. They comment:

For all this it was invaluable training and had it not been carried out the Battalion might have fared badly in the invasion … There was so much to learn about the new technique of landing a complete army on an enemy held coast and so little time to do it.

George Iceton also mentions the number of accidents occurring because of the use of live ammunition in training. One man was killed by a malfunctioning bomb, others seriously wounded by gunfire. But Iceton had been called up in 1939 aged 19 and had fought his way through many battles in France and the Middle East, so he seems to have taken it all in his stride by the grand old age of 23. The Kabrit training was to culminate in Exercise Bromyard [[16]], involving the movement of 16 ships, 23,000 men and 350 vehicles in a full-scale landing in the gulf of Aqaba, using live ammunition. This major exercise took place in June, just a month before Operation Husky, the Sicily landing which was apparently bigger than the D Day landings in France two years later. It was believed+ that Montgomery was on hand to watch the exercise and he certainly addressed the troops with a pep talk about the coming invasion the following day. 6/DLI and 8/DLI, Iceton and the two majors, all took part in the 10 July Sicily landings and the 18/DLI 35 Beach Brick was part of the mainland Italian landings at Salerno on 9 September.

Having ‘proceeded’ to the course on 26 April, Fred’s file rather unexpectedly shows that he ‘rejoined 35 Brick HQ from course at CTC’ on 4 May and four days after that, on 9 May, he was admitted to 66 General Hospital in Nuseirat, now a refugee camp in the Gaza Strip: on that date his x category changed from (i) to (ii) — sick. But 10 days later on 19 May, he was discharged from hospital to 35 Brick Increment HQ, and re-attached to 18/DLI. This is the first appearance of the word ‘increment’ attached to Brick HQ: the London Gazette supplement refers to two increments for attachment to formations for advice on combined operations, planning and training. So presumably that was Fred’s new assignment in Kabrit. He would have been working in the planning increment while still attached to 18/Durham Light Infantry, his new regiment both for Exercise Bromyard and the still secret invasion of Italy.

The next entry, on 11 June, suggests that something alarming had happened. A few of the usual army squiggles in this entry defy interpretation but those that can record that Fred was admitted to a Casualty Clearing Station (ccs), his status changed to sick list, and he ceased to be attached (ctba) to the Durham Light Infantry. On 29 July 1943, about seven weeks later, he was transferred to 3 Com Depot (the Nathanya, ducks and turkey, convalescent depot) yet again and he remained there until 6 January 1944. Thus another six months out of his life. Wikipedia describes Casualty Clearing Station as a medical facility behind the front line used to treat wounded soldiers. There is no way he could have been kept in a casualty clearing station for seven weeks so, once stabilised, he must have been moved to a hospital; perhaps one of the incomprehensible squiggles signifies which one. An Exercise Bromyard file held at the National Archives in Kew consisting of telegrams between the Foreign Office, the British Minister at Jedda, the Minister of State in Cairo, and the High Commissioner in Palestine details the political, diplomatic and logistical planning for this major exercise. It also names the two hospitals designated to receive casualties from the exercise. Of the two, Fred was probably taken to British General Hospital 15 in Cairo. Whatever led to the Casualty Clearing Station on 11 June, whether a fall from the escarpment, a wound from live ammunition, or something else entirely, it must have been quite nasty to require six months for recovery. Bromyard started on 10 June, when 23,000 troops embarked for the two-day voyage to the Gulf of Aqaba where the landing was staged. Was there a mishap during embarkation? Perhaps as a planner he didn’t embark. Sadly, what happened on 11 June remains a mystery.

CIPHER CHESHIRE YEOMANRY AND PALESTINE

Before his discharge in January 1944 from 3 Com depot, Fred had a medical assessment on 17 December 1943. He had been assessed as A1 when he joined up in January 1942, at the age of 35. Now, two years later, he was B1, unfit for general service abroad but fit for base or garrison service at home or abroad. Unusually the note of his discharge in January 1944 doesn’t indicate his x status, nor where he was sent, but by 1 February he was back in hospital again, this time hospital number 12 in Ben Yacov in Palestine. This was a short stay, perhaps for a full assessment. He was discharged on 11 February with the status x(iv), meaning that once again he was available to be posted to a unit. On 14 February he was sent to ME Cipher School. The HQ cipher school was in Cairo but by this stage of the Middle East war, cipher schools had also been established in other locations. A few weeks later, on 6 March 1944, he was transferred to the Royal Corps of Signals. There were a number of entries that day, culminating in one presumably written once his file had been handed to Royal Signals. The Unit column, previously just X, now says ‘5 Lof C sigs, Cipher section’ (which turns out to be important) The record then says: Compulsorily transferred to R Sigs from Inf (Queen’s)in the ranks of Sgmn as Medium Grade Cipher Op & posted to 5 LofC Sigs wef date of transfer Auth UTE/134/1741/1/1dfd 26/3/44 Attended No73 Course at ME Cipher OP Granted addl.pay at 6d per diem as Medium Grade Cipher op under AO 77/43. (6d was sixpence before decimalisation of money, now the equivalent of 2-1/2p). Two further entries on 6 March list him first as unpaid acting lance corporal, then paid acting lance corporal, thus regularising the long entry about the transfer. On 9 June entries show him as first unpaid and then paid Corporal from 30 June.

All these frantic-seeming promotions were formalities. HA Wilson, whose diary I looked at in the Imperial War Museum, describes how he applied to train as a Medium Grade Cipher operator in April 1943. He knew that if he passed he would be transferred to the Royal Corps of Signals and after a month’s probation he would be given a ‘paid stripe’. (That signifies a lance corporal, the most junior grade of non-commissioned officer in the army. They wear a broad V, chevron or stripe, on the upper arm of the uniform; corporals have two stripes and sergeants three.) HA Wilson also knew that if he went on to pass as a Higher Grade Cipher operator he could become a Sergeant if and when he was placed in charge of a group of ‘cipher ops’, as Fred eventually did. Wilson’s original application was held up because an officer with diphtheria had to be replaced and this meant changes down a line of command leaving nobody to train new cipher operators. I came across a number of such passing references to diphtheria, including diphtheria wards in one hospital, so Fred was not alone in suffering from it. Wilson and JR Stokes, the other diarist whose account can be seen in the IWM, both describe some of what the training involved and both give interesting accounts of the somewhat testy relations between signals and ciphers, and intelligence corps and regiments. These are supplemented by a 1971 history of the Cheshire Yeomanry written by an old Yeoman, Lt Col. Sir Richard Verdin [[17]], which has an unexpected relevance.

All the memoirs or histories reveal that it had become increasingly apparent by 1941 that lack of trained cipher operators, signallers, and the equipment to go with them was seriously hampering the British Army fighting over hundreds of miles of desert, sometimes reduced to 24-hour return trips to establish contact between units. (‘British Army’ in this context included New Zealand and Australian units: the then Commonwealth was without frontiers.) The role of ‘enemy’ for the Bromyard landings in the Gulf of Aqaba was played by soldiers of the Indian regiments, as mentioned by diarist HA Wilson who was a participant in Bromyard. Auchinleck, as C-in-C ME and GOC Eighth Army was constantly appealing for reinforcements: 6,000 signallers short, wirelesses useless when chargers broke down on vehicles, amateurish officers reduced to passing messages en clair (unenciphered). Whitehall’s response was predictably miserly, pleading shortages of men and materials. In February 1942, Auchinleck had taken measures into his own hands to some extent by unilaterally ordering two mounted cavalry regiments, the North Somerset Yeomanry and the Cheshire Yeomanry, to dismount from their horses and turn themselves into signals units. These historic regiments, anachronistically but successfully, had been fighting Vichy French forces in Syria [[18]] and Lebanon. An article in the Manchester Evening Chronicle of June 1941 describes yeomanry horsemen firing rifles and machine guns at three Vichy aircraft which eventually dispersed in the face of the fire. The article mentions that ‘one of the horses died of excitement’. In late 1941 when the German advance in Russia seemed to be gaining ground, there were fears that they would then invade Syria and so increase the pressure on the British Army. The Yeomanry forces were excitedly preparing themselves as mounted saboteurs behind the lines in the trackless, mountainous regions. Winston Churchill had enjoyed taking part in the 1898 Battle of Omdurman, the last major cavalry charge of the British Army, but in contrast to his usual propensity for romance, he had been questioning the usefulness of mounted cavalry as against the need for tank and other armoured regiments in this modern war. Some cavalry had already lost their horses. For example, the Staffordshire Yeomanry, after cavalry service in Palestine in 1940, converted to tanks in 1941 as part of the Royal Armoured Corps. Verdin in his history of the Cheshire Yeomanry describes the shock and dismay when their Commanding Officer received Auchinleck’s orders, which he claims came as a complete surprise, upsetting their plans for harrying the Hun in the Syrian mountains. Boring old signals were not what they wanted to do. However, Verdin assumes that Yeomanry volunteers were in fact just the kind of bright, intelligent men needed in such units. The next challenge was to decide between two Royal Corps of Signals units on offer. One was to be responsible for signals in Palestine, Iraq, Trans Jordan, GCHQ and all pumping stations, the other to provide communications between Army and RAF which would mean being scattered between air bases. The Cheshires decided that they wanted to stay together as a unit so they chose the first option. They had the choice because the Cheshire Yeomanry was senior to the North Somerset who became the 4th Air Formation Unit of Royal Corps of Signals. The Cheshire Yeomanry moved to Palestine as 5 Line of Communication Signals (Cheshire Yeomanry), Royal Corps of Signals. Verdin relates how the Yeomanry had insisted on keeping their name.

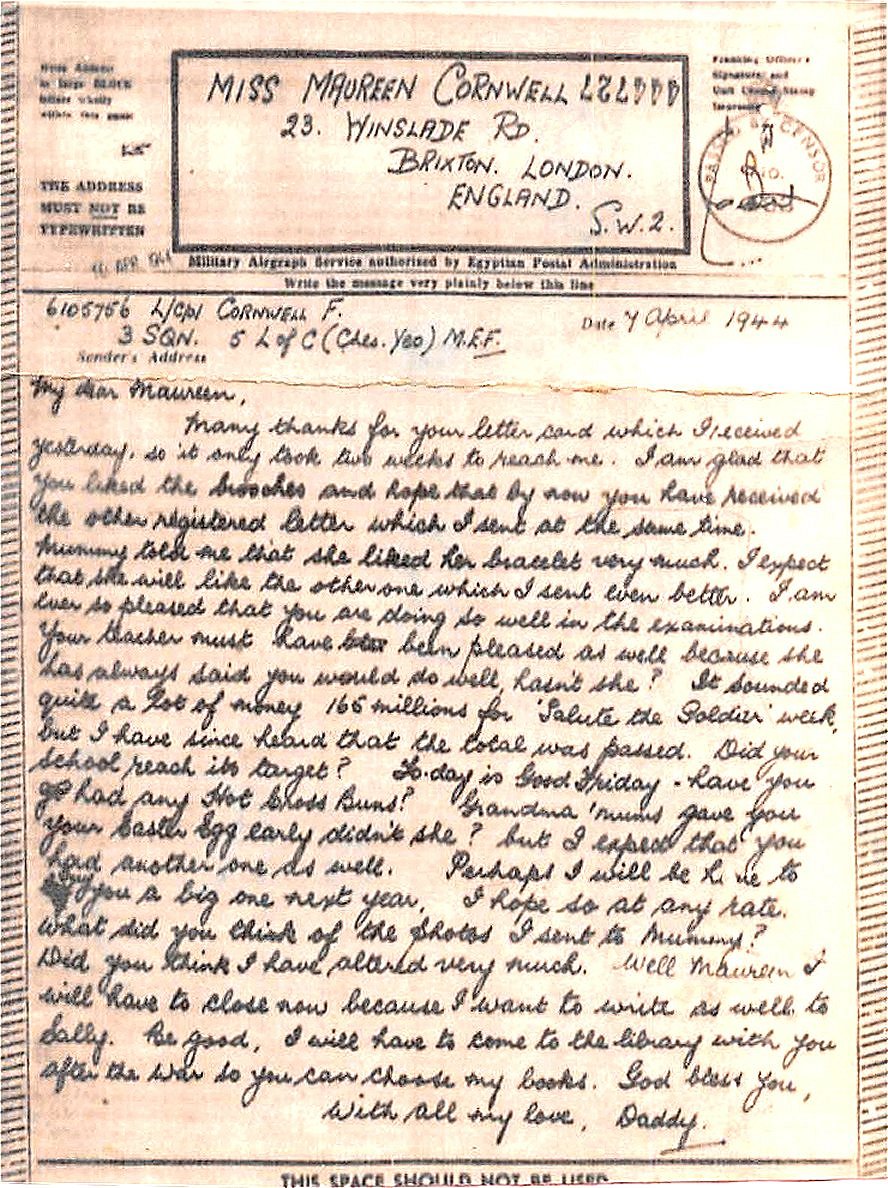

One of our few surviving letters from Fred was written to me on 7 April 1942 (above): the return address was ‘3 SGN 5 Lof C (Ches Yeo) MEF’. I don’t know what we thought any of this meant at the time and of course it gave no indication of where it was. Fred had joined them in Palestine and, according to Verdin, a lot of the Yeomanry were drifting off to Officer Training Units which is what they would have done in 1939 if they hadn’t volunteered to ride their horses in service of their country. I wonder what kind of welcome an oik from the Infantry was given by these unhorsed young men from leafy Cheshire. The Royal Corps of Signals was having to expand at a rapid rate to cope with the demands of total war and the role of the Yeomanry units as newly adopted regiments in the Signals Corps was to provide the manpower and structure needed to support the work of the signallers and cipher operators – accommodation, food, discipline, medical services, technical services, all the administration a regiment needs. JR Stokes and HA Wilson both describe the tension between conventional signals and the cipher operators. When Stokes began training as a cipher operator in January 1943 he was told that until recently cipher operators had remained members of their original regiment and had been under the control of Intelligence Corps at Divisional HQ with Royal Signals just providing accommodation and support. Wilson was told in April 1943 that ciphers had been a branch of General Staff Intelligence but had expanded to such an extent that it had been convenient to transfer them to Royal Corps of Signals but ‘we don’t like Signals and Signals don’t like us’. Stokes was in Burma with Wingate and the Chindits by April 1943 when for the first time cipher operators marched with the Royal Signals columns. One cipher op alongside the wireless operators. Stokes lists the responsibilities of the Signals Corps, whose units were identified as Line of Communications, or LOC, Signals. Wireless operators who used Morse code, telephonists, telephone engineers, motor cyclists, armoured vehicles, linesmen, were all needed to connect the fighting forces with their supply base and, from 1943, Cipher operators had a specific individual role within the units.

One of our few surviving letters from Fred was written to me on 7 April 1942 (above): the return address was ‘3 SGN 5 Lof C (Ches Yeo) MEF’. I don’t know what we thought any of this meant at the time and of course it gave no indication of where it was. Fred had joined them in Palestine and, according to Verdin, a lot of the Yeomanry were drifting off to Officer Training Units which is what they would have done in 1939 if they hadn’t volunteered to ride their horses in service of their country. I wonder what kind of welcome an oik from the Infantry was given by these unhorsed young men from leafy Cheshire. The Royal Corps of Signals was having to expand at a rapid rate to cope with the demands of total war and the role of the Yeomanry units as newly adopted regiments in the Signals Corps was to provide the manpower and structure needed to support the work of the signallers and cipher operators – accommodation, food, discipline, medical services, technical services, all the administration a regiment needs. JR Stokes and HA Wilson both describe the tension between conventional signals and the cipher operators. When Stokes began training as a cipher operator in January 1943 he was told that until recently cipher operators had remained members of their original regiment and had been under the control of Intelligence Corps at Divisional HQ with Royal Signals just providing accommodation and support. Wilson was told in April 1943 that ciphers had been a branch of General Staff Intelligence but had expanded to such an extent that it had been convenient to transfer them to Royal Corps of Signals but ‘we don’t like Signals and Signals don’t like us’. Stokes was in Burma with Wingate and the Chindits by April 1943 when for the first time cipher operators marched with the Royal Signals columns. One cipher op alongside the wireless operators. Stokes lists the responsibilities of the Signals Corps, whose units were identified as Line of Communications, or LOC, Signals. Wireless operators who used Morse code, telephonists, telephone engineers, motor cyclists, armoured vehicles, linesmen, were all needed to connect the fighting forces with their supply base and, from 1943, Cipher operators had a specific individual role within the units.

HA Wilson describes the kind of men who were initially selected for training as Cipher Ops: a special kind of intelligence was required and a good general knowledge was essential, so too were powers of observation. It seems that this would help in working out the meaning of possibly corrupted messages and also in noticing deliberately false messages. It was often necessary to disguise short important messages in longer texts which made sense without highlighting the essential core. There was also the need for a very good memory. When training began they were handed files full of papers, books full of figures, not allowed to remove them from the room and not allowed to make notes. In those early days, Wilson was confronted with Double Transposition which an internet site [[19]] describes as:

one of the most secure hand ciphers used in the Second World War. It was used by both the Allies and the Axis, and served both well…. In the United States, information about cryptanalysis of the cipher remained classified until a few years ago.

And this from Wikipedia [[20]]:

double transposition was generally regarded as the most complicated cipher that an agent could operate reliably under difficult field conditions.

Later Wilson describes his High Grade Op course as including strings of figures, touch typing at speed, encipher, decipher, write down results, 5 groups a minute, 10-minute speed tests, hundreds of abbreviations and groups committed to memory. And the operator had to be able to take his machine to pieces and re-assemble it. All his family knew that Fred had a fantastic memory and mathematical brain and was a voracious and speedy reader. (I’m not sure about assembling machinery.) Both Stokes and Wilson stress the need for secrecy. Unless they were working in Division HQ they had a metal box with a key which was never to be let out of their sight. As far as possible they were to work alone and no unauthorized person whatever the rank was allowed to watch them. High Grade cipher was never to be shown to anyone, not even a Signals or Staff (meaning senior) Officer. Cipher matters were never to be discussed. Stokes described the way that Cipher ops worked with Signals. Messages were coded and passed to wireless operators for transmission by Morse Code, enciphered messages received were passed to cipher ops for translation. Messages classified as MOST SECRET were handled only by cipher ops. At that time MOST SECRET signified the highest level of UK security classification but in 1943 this was dropped for the US phrase, TOP SECRET, to ensure that US and UK had consistent systems. They were still reserved for cipher ops.

It was as a Medium Grade Cipher Op in March 1944 that Fred joined the Cheshire Yeomanry in their new role in Palestine. As usual we don’t know where he was physically but the chances are that he was based in the Allenby Barracks, situated midway between Jerusalem and Bethlehem. An anonymous contribution to the Royal Signals Museum comes from someone who was called up aged 18 in August 1944 [[21]]. Although war was at its height in Europe and D Day was six months away he was trained as an OWL, ‘operations and wireless line’, and sent to Palestine Command Signals Regiment which seems to have absorbed the Cheshire Yeomanry. He found himself in the Allenby Barracks, wholly occupied by signallers. The signals office was two miles away in Jerusalem, behind the King David hotel. A Captain posted to Palestine Command HQ in Jerusalem in January 1946 (as described in ‘The Vital Link’ by Philip Warner) found that military operations for the whole of Palestine were housed on the top floor of the hotel: a little naïve, he thought. Dances were held on Saturday nights in the hotel but the participants, officers of course, had to dance with their revolvers attached. Growing tensions between Arabs and Jews and both those groups with the British Mandate made for powder keg conditions. The young OWL describes the remit of Palestine Command as communications centre for the Middle East all over Palestine and through to Cairo. He talks of the daily terrorist threats from the Irgun and the Stern Gang, and travel only in armoured vehicles.

Fred served a couple of months as a cipher op, paid acting corporal, presumably living in the Allenby Barracks and working in or near the King David hotel, until 17 August, when he was once again on the sick list and transferred to General Hospital 16 in Jerusalem. His rank reverted to Sgmn (Signalman) but his days continued to count towards his appointment as a w/cpl instead of an acting corporal and he would continue to draw his corporal’s pay for 21 days. In fact he was discharged after just nine days and re-instated as a paid acting corporal until 7 September when he was appointed w/cpl. The ‘w’ apparently stood for ‘war’ and distinguished between those who were in the regular army and those  who were just serving for the duration of the war. The day after this nominal but no doubt appreciated promotion, Fred was shown as TOS (taken off strength) from 5 L of C Sigs Cipher Sec and transferred to 588 Army Cipher Pool Section.

who were just serving for the duration of the war. The day after this nominal but no doubt appreciated promotion, Fred was shown as TOS (taken off strength) from 5 L of C Sigs Cipher Sec and transferred to 588 Army Cipher Pool Section.

I haven’t picked up any reference to this unit in memoirs or histories. The necessary culture of secrecy which shrouded cipher work seems to have outlived those who worked in it. It seems likely that such a unit would have functioned as part of the governing administration of Palestine, a British Mandated Territory from 1917 until we withdrew in 1948, rather than working in support of military operations which was the role of the Royal Signals. In the Cipher Pool, Fred would certainly have been working in the King David hotel, in the South Wing if he was working for the Secretariat (administration).

Much of the following account of the King David hotel is taken from a Wikipedia article. Rooms in the hotel had first been requisitioned in 1938 on a temporary basis when there had been plans to build a permanent building for government and army HQ. But these plans were cancelled on the outbreak of war. By the war’s end more than two thirds of the hotel was used by government and army. The military telephone exchange, staffed by Royal Signals, was in the basement. In March 1946, Richard Crossman, the Labour MP on a visit, gave this description of the hotel:

Private detectives, Zionist agents, Arab Sheiks, Special correspondents, and the rest, all sitting around about discreetly overhearing each other.

(That could be any Sheraton hotel lobby in any capital of any third world country we have known.) The US security analyst, Bruce Hoffman, wrote that the hotel housed the nerve centre of British rule in Palestine. After just a couple of months in this unit, perhaps a probationary period, Fred was sent to the High Grade Cipher School on 1 November 1944. On his return a month later as a qualified High Grade Cipher operator, he was granted additional pay of 1/- (one shilling, today’s 5p) a day. For the next year, his army rank remained as w/cpl until 15 January 1946 when he was promoted to unpaid acting sergeant, TOS from 588 army cipher pool and transferred to 589 army cipher pool. After a month there he became a paid acting sergeant, which would have meant that he was now in charge of a cipher pool section. I assume that 589 was doing the same work as 588 and veterans of 589 have been no more forthcoming than veterans of 588 with their memoirs.

Fred’s next ‘promotion’ would have been to paid w sergeant, not regular, but in fact the war was long over. By this time it was nearly six months since VJ Day, which had signalled the end of the second World War on 15 August 1945; but British responsibilities for Palestine and the ever deteriorating relations between Jews and Arabs, and both with the British, meant that more troops were being sent to Palestine than were being withdrawn. Specialists such as cipher operators and officers in the Royal Signals, as well as tradesmen in the RAMC, were being kept on even if they had compassionate reasons for leaving. MPs questioned this in the House of Commons and were told that there was a general shortage of cipher operators, but MEF (Middle East Forces) were being given priority over all other theatres. In his letter to me from 5 L of C, 7 April 1944, Fred had said: Today is Good Friday. Grandma Mums gave you your Easter egg early didn’t she? Perhaps I will be home to give you a big one next year. That date had been missed but, just a year later than he had hoped, on 4 April 1946, his file reads: TOS from 589 Cipher Sect. CTBE to HG cipher pay at 1/-pd (taken off strength from 589 Cipher sect. ceased to be entitled to High Grade cipher pay at one shilling per day). It was a pithy but very welcome signal that he was nearly on his way home. On 13 April he was SOS MEF on embarkation for UK. On 22 July 1946 a Jewish militant group, Irgun, attacked the King David hotel: dressed as Arabs pushing milk churns, they got through the Royal Signals in the telephone exchange in the basement and planted their milk churn bombs below the Secretariat and Military offices. A whole section of the hotel was brought down and 91 people were killed. But by that time Fred, who had spent two years working in those offices, was safely back home with his family in Brixton. At age 35 he had been pronounced A1 fit but sadly he died at the early age of 59. Those four years of military service had taken their toll.

It must have been a miserable and frightening four years out of his life, but his testimonial shows how stoically and uncomplainingly he did his duty and what valuable work he was able to do once his acute intelligence was acknowledged and required. And after all that he buckled down to a pretty grinding civilian job again, with no bravado or brave talk. People of that generation set us a good example. And as I sought explanations of the squiggles on his file and read the documents, I was constantly impressed by how competently, and speedily, and fairly, problems were confronted and dealt with and solved in those perilous years. All these years later, for all our increased knowledge, we could still learn from our forebears.

Jane Maureen Barder (née Cornwell)

London, May 2016

~-~-~-~-~-~-~-~-~-~-~-~-~-~-~-~-~-~-~-~-

For a printable version of this web page, click here.

List of Sources and References

[1] Anderson shelters: see http://www.andersonshelters.org.uk/

[2] ARP: Air Raid Precautions. See http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/timeline/factfiles/nonflash/a6651425.shtml

[3] Private papers of JR Stokes and HA Wilson at the Imperial War Museum. See http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1030004720

[4] Queen’s Royal Regiment in the middle east: see http://www.queensroyalsurreys.org.uk/ww2/middle_east/qme001.shtml

[5] For Gormley’s voyage on Strathallan, see www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/93/a4871793.shtml

[6] Kenneth Kettle on Strathallan and Alam Haifa: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/12/a7399812.shtml

[7] Scarlet Finders: see http://www.scarletfinders.co.uk/112.html

[8] Convalescent Depot 3: Roza El-Eini – 2004 – ?Political Science. https://books.google.co.uk/books?isbn=1135772401

[9] For interpretation of ‘x list’, see http://ww2talk.com/forums/topic/15663-x-lists-service-records/

[10] Durham Light Infantry (DLI): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Durham_Light_Infantry

[11] Beach Bricks: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beach_groups

[12] Beach Bricks: http://www.rafbeachunits.info/List_of_Units/Middle_East_Beach_Bricks/middle_east_beach_bricks.html

[13] ‘Operations in North Africa and the Middle East 1942-1944’ by John Grehan and Mace:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B00XIMPBV0/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?_encoding=UTF8&btkr=1

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011678

[14] ‘8th Battalion The Durham Light Infantry 1939–1945’by Majors Lewis and English: http://books.national-army-museum.ac.uk/8th-battalion-the-durham-light-infantry-1939-1945-pr-26536.html

[15] Iceton, George Edward IWM interview (including audio tape of interview, reel 49): www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011678

[16] Bromyard: https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/37786/supplement/5579/data.pdf

[17] Sir Richard Verdin, “Cheshire (Earl of Chester’s) Yeomanry, 1898-1967” http://amzn.to/1S2XRfs

[18] Mounted machine gun section, Cheshire Yeomanry: painting in Imperial War Museum: http://media.iwm.org.uk/iwm/mediaLib/148/media-148187/large.jpg?action=d&cat=art

[19] Cipher ops: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/decoding/doubtrans.html

[20] Double transposition cipher: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transposition_cipher#Double_transposition

[21] Account of Palestine Signals, 1946: http://www.royalsignalsmuseum.co.uk/palestine-reflections/