The Kosovo-Georgia connection

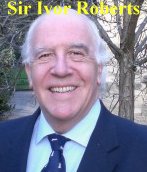

In writing about Kosovo and Georgia, I am handicapped by having no first-hand experience of the area, apart from having served in Moscow in the early 1970s, including a brief visit to Georgia during that time. So it’s reassuring to find that someone with perhaps more extensive first-hand knowledge of the Balkans than almost any other UK commentator has written an analysis which closely mirrors my own (also e.g. here and here). Sir Ivor Roberts was appointed Chargé d’Affaires and Consul-General in Belgrade in March 1994, and after recognition of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia by the United Kingdom, became Ambassador. During his time in Belgrade he conducted negotiations on behalf of the international mediators (Lord Owen and Carl Bildt) with both the Yugoslav authorities and the Bosnian Serbs. He was also involved in the negotiations for the release of British soldiers held hostage by the Bosnian Serbs in May/June 1995. He left Belgrade at the end of 1997, barely two years before NATO started to bomb it. From January 1998 to February 1999 he was on a sabbatical as a Senior Associate Member of St. Antony’s College, Oxford, writing and lecturing on his experiences in Yugoslavia. He served subsequently as British ambassador to Ireland and then Italy. He retired from the Diplomatic Service in September 2006 on his election as the President (Master) of Trinity College, Oxford, his current appointment.

Sir Ivor has written quite extensively about Kosovo, most recently in an article in The Tablet in which he traces the origins of the current Georgia-Russia conflict directly to western misjudgements over Kosovo. You can read extensive extracts from his article here. I urge you to do so. You can read the full text online if you are a subscriber to The Tablet, or in hard copy if you buy it.

Sir Ivor has written quite extensively about Kosovo, most recently in an article in The Tablet in which he traces the origins of the current Georgia-Russia conflict directly to western misjudgements over Kosovo. You can read extensive extracts from his article here. I urge you to do so. You can read the full text online if you are a subscriber to The Tablet, or in hard copy if you buy it.

Not only did western mishandling of the Kosovo problem (and the misconception that western military intervention against Yugoslavia over Kosovo had been a success) encourage further and even more disastrous blundering in Iraq: it has also had seriously negative consequences for the west’s relations with Russia and for Russian perceptions of western intentions — consequences that we see now in Georgia and in western impotence in the face of that challenge. It’s too late to undo those Kosovo mistakes now, but it’s not too late to begin to recognise them as mistakes and to try to learn some lessons from them in our future approach to Georgia (and Ukraine) in relation to Russia. For US, UK and some other western leaders to go on about Russia’s “unacceptable” behaviour in Georgia[1] and to reject any suggestion that Russia, like any other powerful state, will seek to insist that its smaller neighbours pay regard to Russian interests, simply compounds past mistakes instead of facing reality. Not only Georgian but also Ukrainian leaders, and policy makers in Washington and London, would do well to study the history of Finland’s sensitive handling of its relations with Russia — as well as Ivor Roberts’s shrewd analysis of where we, or they, have gone so badly wrong.

[1] Of course recent Russian behaviour in Georgia has been disgraceful, brutal and disproportionate, and deserves to be condemned. But it’s as well to remember that even before the recent conflict Russia had military forces stationed legally in Georgia under an earlier agreement with the Georgian government; and that in numerous ways, geographically, culturally, historically and ethnically, Georgia is indelibly written into Russia’s DNA (as indeed is Ukraine). To understand how Russians react to western bluster about Georgia’s inalienable right to join NATO in complete disregard of Russian objections, it’s only necessary to consider how any American administration would have reacted if the Russians had recruited Cuba — or Mexico — as a member of the Warsaw Pact: and indeed how the US did react when the Soviet Union started to station missiles in Cuba. For George W. Bush of all people to berate Russia for ‘invading’ the sovereign territory of independent Georgia, after his own record in Iraq, requires a certain chutzpah. And to say, as Bush has said, that the days of “spheres of influence” are over is cloud cuckoo land. Every big and powerful state, including throughout most of its history the United States, seeks to ensure that its neighbours pay due regard to its vital interests and are not allowed to fall under the control of its foreign adversaries or potential enemies. Add to that Russia’s built-in paranoia about the need to protect itself against the threat of western attack, and you can’t easily mistake Russian actions in its ‘near abroad‘ for simple aggression. Like the man said, just because you’re paranoid, it doesn’t mean they aren’t out to get you.

Brian

to say, as Bush has said, that the days of "spheres of influence" are over is cloud cuckoo land

Yes and no. Many years ago I reviewed a book by an American historian about the post-war negotiations between the Big Three at Potsdam, Yalta and Teheran. What made it difficult to review – difficult to understand, in point of fact – was its author's blithe confidence that a 'sphere of influence' was (a) a bad thing and (b) something the US neither had nor wanted to have. Stalin wanted a sphere of influence for the USSR; Churchill wanted a sphere of influence for the UK; but Roosevelt and Truman simply wanted the whole world to be open… to the influence of the US. Quite different.

Brian writes: Thanks for a fascinating and illuminating comment. I still think that there's a sense in which the United States has always regarded the western hemisphere as its sphere of influence — since the Monroe doctrine of 1823, anyway — but you are right that on another level the US regards the whole world as its sphere of influence, especially since becoming the sole superpower at the end of the cold war. Perhaps it's useful to distinguish between a big country which claims the right, almost sanctified in international law, to a sphere of influence around its borders within which it's entitled to do virtually what it likes; and a big country which as a matter of plain reality exerts its influence on its smaller neighbours' affairs to ensure that they don't act in ways that threaten its vital interests and in particular that they don't become subordinate to any other big country or alliance which is a potential or actual adversary or enemy. The first case is obviously illegitimate, since no such right of intervention or interference in another country's internal or external affairs can exist in international law. The second case is simply a matter of observable fact, whether one approves of it or not. That's how big countries behave in their relations with their smaller and weaker neighbours. In 1940 Churchill seriously considered occupying the Republic of Ireland to prevent it offering bases or other military facilities to Germany. Russia assembled a formal empire as its sphere of influence, then converted it into the Soviet Union, and expanded it further into the Warsaw Pact. The failure of the USSR compelled it to dissolve the Warsaw Pact and acquiesce in the independence of the former republics of the USSR. Now, beginning to reassert itself as a world power thanks to its geography, history, oil and gas, nuclear and Security Council status, etc., Russia is once again seeking to establish a protective buffer of respectful, but not necessarily vassal, states and to limit their freedom to act in ways that might threaten Russian interests and security. It's surely important not to confuse this inevitable (and not necessarily harmful) process with an attempt to re-establish Russian sovereignty and full control over the whole of the former USSR, still less over the former Warsaw Pact. Finland has managed to lead a fully independent existence on Russia's border by establishing the implicit rules of its relations with Russia and being careful to observe them. It would be helpful if (e.g.) Georgia and Ukraine would follow the Finnish example — and if presidents, prime ministers and foreign ministers in Washington, London and parts of eastern Europe would see this process, however messy at times, as a contribution to peace and stability, not an expansionist menace to be resisted at every turn.

The Roberts analysis is certainly thought-provoking, and he is surely right that Geeorgia's President Saakashvili would have done well to study the skill with which the Finns have played their limited hand before recklessly tweaking the Russian bear's tail. I wonder, though, whether the division of opinion over the latest events in Georgia is, or (more important) need be, as rigidly demarcated as you suggest. I can see defensible arguments in both of the camps you describe.

It was a little disorienting to hear such a romantically idealistic supporter of the United Nations as yourself briskly accepting as a fact of life the right of great powers to bully and cow smaller states on their borders on the realpolitik argument that this is what big powers have always done. Maybe so, though I note that the examples you choose of allegedly similar American and British behaviour date either from the Cold War period of irreconcilable ideological conflict when the Soviet military threat was both real and great, or from the Second World War and Britain's imperial past, when the context, to put it mildly, was somewhat different. Khrushchev proposed siting offensive Russian nuclear weapons in Cuba aimed at targets in the US at a time when the two superpowers were locked in a state of mortal enmity, hardly comparable to the installation of a defensive nuclear shield in Poland to provide protection from a nucear-armed Iran nearly 20 years after the end of the Cold War when the West poses no realistic military threat whatever to Russia. I accept that there are good reasons for questioning the wisdom or necessity for the Polish nuclear shield, and I would agree with many of them. I am simply saying that the two situations are not comparable. Likewise, I can only hope you were not serious when you suggested that a Russian occupation of Georgia would be little different from a British occupation of Ireland during WWII had that small neighbour been so foolish as to offer military bases and other facilities to Nazi Germany, one of the most brutal and evil regimes of modern history which was then threatening not only Britain but most of the other nation-states of Europe with annihilation or slavery under Teutonic overlordship.

You make much of Western (particularly American and British) double standards. You certainly have a point. The West regards national self-determination as an important democratic right, and has championed it in the case, for example, of Kosovo. We cannot, in principle and fairness, deny the same right to Ossetians and Abkhazians should they wish to exercise it.. You might profitably, however, have also noted in passing Russia's hypocrisy in posing as the defender of the rights of separatists in Georgia while ruthlessly crushing such movements on its own territory.

There are certainly questions to be asked about the raison d'être of NATO nearly two decades after the dissolution of the Soviet communist empire. Perhaps the time has come to take up the old French idea of looser military links with the US, with the Eurogroup within NATO developing into the independent military wing of the EU. In due course, unrealistic and crystal-ball-gazing as it may seem now, I do not see why Russia should not be invited to join both NATO (or the Europe wing of it) and the EU. In the new world of regional superpowers, and Islamist extremism, Russia and the EU will surely increasingly have shared economic, political and cultural interests to defend that are more importance than their differences.

On the more immediate question of NATO and Georgia, I agree with most of your other commentators that it was sensible to at least to delay the offer of NATO membership to that country when it was beset by separist disputes in which Russia has at least a quasi-legitimate interest. The difficulty now is that the latest Russian actions have made it difficult for NATO to refuse membership without appearing to appease Russian bullying. Perhaps NATO membership should be offered on condition that Georgia first permit UN-supervised referendums, without the presence of Russian troops or "peacekeepers", in Abkhazia and South Ossetia to determine the future of those territories and their peoples. If that were rejected by either Georgia or Russia, and no doubt quite possibly both, then so be it. The West's position would at least have been consistent and principled.

I think national self-determination remains an important democratic principle, as is the right of independent nations to choose their friends and alliances, provided this choice is not a blatant act of hostility towards, or a real and demonstrable threat to the security of, any other nation. By the same token, alliances have every right to be discriminating in considering applications for membership. I presume, Brian, that as a good democrat you, like me, would feel bound to accept, say, the secession of Scotland if that were the clearly expressed wish of the Scottish people, however disastrously mistaken, for both England and Scotland and the United Kingdom as a whole, we might think that outcome to be. I do not think that the right to self-determination or independence can simply be brushed aside as non-applicable to the so-called "near abroad" of big powers.

Michael Hornsby

Brian writes: Michael, thank you for putting so many pertinent and stimulating questions and challenges so courteously. I think there are good answers to all of them, which I shall try to provide later. For the moment, let me just record one vital reservation about self-determination, a topic which was central to much of my working life. It's beset with enormous difficulties, as I'm sure you will agree. Nowhere in the UN Charter is it described as a 'right', only as a 'principle'. International law has never, I believe, attempted to define the kind of community — ethnic group, nation, province, large, small — that can legitimately claim self-determination, and so far as I know Russia has not defended its intervention in Georgia on the basis of protecting the 'right to self-determination' of South Ossetia or Abkhazia, only on its right to protect its own citizens in those areas (countries? provinces?) against an armed attack of great savagery by the Georgian army and other Georgians. Similarly, it was never obvious that 'self-determination' was the right or necessary 'solution' for the Kosovo Armenians, either in 1999 or earlier this year. There were, and are, strong arguments for accepting that some areas and peoples which have achieved or been granted extensive autonomy may be best left in a kind of indefinite limbo, given international material help but without outside powers interfering to bring the question of ultimate status to the crunch if that's likely to result in violence and division. NATO, and especially the US and UK, insisted on bringing the Kosovo problem to a head when it would have been far better to leave it under international protection with its formal status unresolved. Saakashvili would have been much better advised to leave South Ossetia and Abkhazia with their autonomy and ambiguous status undisturbed: his electoral promise to restore them to Georgian government control was reckless, and his resort to military attack to fulfil that promise even more so. American and other western encouragement of the idea that NATO membership was in sight and that western military support in the event of conflict with Russia was assured was every bit as reckless. Not all problems can be resolved whenever they itch a little; some are best left for opinions and ambitions to develop and change.

And as for Scotland, I would not acquiesce in the immediate break-up of my (and your) country simply on the basis of a vote for independence by the Scots alone. I have got into deep trouble, and been roundly abused, on another blog for saying that the English, Welsh and northern Irish, not just the Scots, have a stake in the future of the UK and they too have a right to be consulted about alternative options. It seems to me fruitless to argue about whether Scotland has a 'right to self-determination' as a separate entity: the only helpful question is what will be best for all the parts and peoples of the United Kingdom if one significant group wants to leave it. In my view — as diligent readers of this blog may remember — it should be possible to devise a federal system for the UK which would give Scotland (and the other three nations of the Union) full control of virtually all their affairs while still preserving the UK as a sovereign an independent state: this would in effect allow Scotland, and the rest of us, to have our cake and eat it. If we were led by statesmen, such a dispensation would by now be in the process of being worked out by the leaders of all four nations, without waiting for a vote on independence by the Scots, which would (and probably will) make any alternative outcome infinitely more difficult to bring about. But we are not, sadly, led by statesmen, and we are sleepwalking into disaster for lack of political courage and imagination. It's surely clear, though, that there is really no analogy between Scotland and either Kosovo or South Ossetia or Abkhazia, or, come to that, Chechnya, the Basque country or the Walloons of Belgium, and that any attempt to approach any of these problems in terms of the 'right to self-determination' simply complicates issues which are already complex enough. Our motto should echo Lenin: What is to be done?

More later. That will do for now!

You mention the Northern Irish stake in the United Kingdom. The government have given the people of Northern Ireland an assurance that they may remain part of the United Kingdom as long as a majority of them wish to do so. The background to this is the insistence of the majority community that they should not be cut off from the island of Great Britain and left as a minority in the island of Ireland.

What happens to this undertaking if Scotland becomes independent? Clearly it can not simply lapse, but who inherits it? It seems clear that the people of Northern Ireland should be allowed to choose their partner, and almost equally clear that they would choose Scotland rather than England, which they deeply distrust.

Once it is clear that independence for Scotland is on the agenda this question should be publicly aired, and settled in advance so that all concerned know what they may expect. It might deter a few Scots from voting for independence. It would certainly make me, an Englishman and therefore presumably not likely to have a vote on the matter, more reconciled to a decision by Scotland to break away.

While we are about it, we might throw in the Falkland Islands, who have had a similar assurance and who also have much more in common with the Scots then with the English.

Brian writes: These are fascinating speculations, but I doubt if we need to lose much sleep over them. (1) It seems to me unlikely that Scottish secession from the UK would directly affect Northern Ireland's constitutional status as part of the UK, or whatever would be left of it. Nor would it trigger any requirement for the Northern Ireland people to choose between Scotland and England (or rather England-and-Wales). The UK itself would continue to exist as a sovereign state without Scotland. Scotland, by contrast, would have to apply for UN and EU membership and seek recognition from other states (although if the UK recognised it promptly, others would no doubt follow suit; if not, not; and the UK would be able to veto Scottish membership of both the UN and the EU if it wished, however improbably). (2) It seems unlikely in the extreme, to me anyway, that if a majority of the adult population in Northern Ireland voted to secede from the UK, before or after Scottish independence, that majority would prefer to be united with Scotland rather than with the Republic of Ireland — unless of course the current Protestant majority were to seize the opportunity of voting to secede from the UK and uniting with Scotland as a means of heading off the risk of a future Catholic majority voting for reunification with the rest of Ireland. Equally unlikely, surely.

But what is that in the corner of your cheek, Oliver? An olive? Or your tongue?

Some more responses to Michael Hornsby's Comment above, to add to my immediate response appended to it:

MH: I wonder, though, whether the division of opinion over the latest events in Georgia is, or (more important) need be, as rigidly demarcated as you suggest. I can see defensible arguments in both of the camps you describe.

BB: I agree that of course both points of view are tenable; and some parts of them may be common to both camps (e.g. that both the Georgian and Russian governments and their armed forces have behaved very badly, although in somewhat different ways). But other parts are surely irreconcilable: I hold that NATO should give up any thought of recruiting Georgia or Ukraine to the alliance; those holding the opposite view think that NATO membership for either or both countries is positively desirable, notwithstanding Russian objections — or perhaps because of them, although it's not easy to see which of the objectives laid down in the North Atlantic Treaty would be promoted by their accession to membership. It would commit the alliance to a guarantee which it would be exceedingly unlikely to honour in the event.

MH: It was a little disorienting to hear such a romantically idealistic supporter of the United Nations as yourself briskly accepting as a fact of life the right of great powers to bully and cow smaller states on their borders on the realpolitik argument that this is what big powers have always done.

BB: I certainly don't think that any country has the 'right' to "bully and cow smaller states on their borders"; I think we need to distinguish between what governments are entitled to do (under international law, or under some unwritten code of international behaviour), and what all countries invariably do in practice, whether we like it or not. I don't think it's right to equate bullying and cowing other countries with exercising influence on them to deter them from acting in ways that threaten one's security or other vital interests, which is what everyone does. The question is which kinds of "influence" — through diplomatic relations, economic pressures, implied or explicit threats of other kinds of pressure, ultimately military action — one country ought to deploy in order to promote its own interests or security vis-à-vis another: which kinds are acceptable and which are not. But it's a waste of time complaining that countries do use whatever potentially effective leverage they possess, in order to deter or prevent their neighbours (and indeed other countries too) from acting in ways that they perceive as threatening their security or interests. Everybody does it and will continue to do it.

MH: I note that the examples you choose of allegedly similar American and British behaviour date either from the Cold War period of irreconcilable ideological conflict when the Soviet military threat was both real and great, or from the Second World War and Britain's imperial past, when the context, to put it mildly, was somewhat different. Khrushchev proposed siting offensive Russian nuclear weapons in Cuba aimed at targets in the US at a time when the two superpowers were locked in a state of mortal enmity, hardly comparable to the installation of a defensive nuclear shield in Poland to provide protection from a nuclear-armed Iran nearly 20 years after the end of the Cold War when the West poses no realistic military threat whatever to Russia.

BB: I don't think it's helpful to treat the cold war as a kind of aberrant blip in an otherwise amiable relationship between Russia and the west. For centuries Russian fear of attack from the west — reinforced by much practical experience — has been a dominant feature of its relations with the outside world, as has the determination of all Russian régimes to ensure that their security is enhanced so far as possible by the creation of a cordon sanitaire of more or less subordinate states around Russia, stretching outwards as far as Russia's military and economic power permits at any particular time. The binding of neighbouring states into a sovereign or imperial union with Russia, and/or the creation of alliances with regional countries which to a greater or lesser extent limit their freedom of action in international affairs, have not been unique to the Soviet Union or to the cold war. Some in the west view the resumption of these moves by Putin as a recrudescence of Russian expansionism, others see it as an inevitable consequence of the recovery of self-confidence and economic power following the humiliating collapse of the Soviet Union — under intense pressure from the west. It creates serious problems for Russia's neighbours, but isn't necessarily a threat to western interests or security more generally. It can be made much more harmful and problematic if western policies seem to Moscow to pose a threat to Russia, as the eastward expansion of NATO (and to a lesser extent the EU) inevitably does, even if we don't see it that way. (But what other reason can NATO have for seeking to sign up Russia's immediate neighbours as members, if not to prevent Russia from exercising influence over them?) And incidentally I wonder if it's right to say that during the cold war "the Soviet military threat was both real and great"? It seemed so at the time, but with hindsight it seems unlikely in the extreme that the Soviet Union ever seriously contemplated attacking the NATO countries of western Europe, still less launching a nuclear or any other attack on the US or Canada. What is beyond doubt is that the Russians genuinely believed that "the western military threat was both real and great". The danger of gross miscalculation by either side was very great, which was probably the only real threat.

As for the American agreements with Poland and the Czech Republic under which the US will station elements of its so-called defensive missile shield in those countries: the whole idea of a defensive missile shield is contrary to the concept of a nuclear balance between the superpowers; nobody believes that the 'shield' has a ghost of a chance of working; nobody apart from a po-faced Pentagon seriously asserts that it's directed against Iran and not against Russia; it forces Russia to devise offensive nuclear weapons that will evade the shield (not all that difficult, technically), thus setting off another nuclear arms race — so bang goes any hope of nuclear disarmament to which all the legitimate nuclear powers are formally committed; and it's perfectly obvious that Polish and Czech motives in accepting these missiles on their soil are rooted in their traditional (and understandable) fear of and enmity towards Russia. It's just one more way of sticking their thumbs up Russia's nose; they don't seriously expect either that Russia will launch a nuclear attack against them (despite recent sabre-rattling by a Russian general), or that if it did, the missile shield would ward it off. Anything more likely to revive cold war fears and attitudes than putting US missiles on Polish and Czech soil is difficult to imagine, unless it's putting them in Georgia or Ukraine. Anyway, there's no direct connection between the US-Polish or US-Czech missile agreements on the one hand, and Georgia's (and then Russia's) latest resorts to military action on the other. The indirect connection is that both are deliberately designed to provoke a strong, paranoid Russian reaction.

MH: I can only hope you were not serious when you suggested that a Russian occupation of Georgia would be little different from a British occupation of Ireland during WWII had that small neighbour been so foolish as to offer military bases and other facilities to Nazi Germany, one of the most brutal and evil regimes of modern history which was then threatening not only Britain but most of the other nation-states of Europe with annihilation or slavery under Teutonic overlordship.

BB: I didn't say the two scenarios were 'little different': I simply cited the serious contemplation by Churchill of occupying Ireland as an example of a bigger country being prepared if necessary to go to extraordinary lengths to protect its security from potentially threatening activity on the part of a smaller neighbour. The differences are only ones of degree. Moscow undoubtedly sees western intentions towards Russia as deeply threatening, and therefore as requiring a strong response. Georgian folly, whether or not actively encouraged by a reckless United States, provided a good opportunity for just such a strong response.

MH: The West regards national self-determination as an important democratic right, and has championed it in the case, for example, of Kosovo. We cannot, in principle and fairness, deny the same right to Ossetians and Abkhazians should they wish to exercise it.. You might profitably, however, have also noted in passing Russia's hypocrisy in posing as the defender of the rights of separatists in Georgia while ruthlessly crushing such movements on its own territory.

BB: I have responded earlier to your comments about self-determination (see reply appended to this). There are too many secessionist problems afflicting numerous countries for any of them to accept any universal 'right of self-determination'; each country adopts different attitudes to different secessionist issues according to the political implications of each. The US and UK (dragging an often reluctant NATO behind them) deliberately engineered a sort of half-baked 'independence' for Kosovo, without Spain, a NATO member, thereby feeling obliged to recognise the 'right' of the Basque country to independence[1]. Same with Russia, South Ossetia and Abkhazia, and Chechnya. There's a vocal movement for independence for Cornwall, but the British government doesn't regard its support for Kosovo secession from Serbia as carrying an obligation to grant 'self-determination' to Cornwall. And so on. It's stretching things too far to call this 'hypocrisy', unless you apply that label to almost every country on the globe. Perhaps you do.

MH: There are certainly questions to be asked about the raison d'être of NATO nearly two decades after the dissolution of the Soviet communist empire. Perhaps the time has come to take up the old French idea of looser military links with the US, with the Eurogroup within NATO developing into the independent military wing of the EU. In due course, unrealistic and crystal-ball-gazing as it may seem now, I do not see why Russia should not be invited to join both NATO (or the Europe wing of it) and the EU. In the new world of regional superpowers, and Islamist extremism, Russia and the EU will surely increasingly have shared economic, political and cultural interests to defend that are more importance than their differences.

BB: NATO lost its whole raison d'être at the end of the cold war and should have been disbanded then, to be replaced (possibly) by a wholly different military structure, perhaps concentrated on peace-making and peace-keeping and set up under Security Council auspices. Russian membership, along with other former Warsaw Pact countries, would then have been natural and indeed obviously desirable. Unfortunately that opportunity was lost, along with many other opportunities to bind Russia and its former allies and client states into a constructive and mutually beneficial relationship with the western world. Instead NATO has been used as a triumphalist stick with which to beat Russia, reviving in the process all Russia's primeval fears about western intentions.

MH: On the more immediate question of NATO and Georgia, I agree with most of your other commentators that it was sensible to at least to delay the offer of NATO membership to that country when it was beset by separatist disputes in which Russia has at least a quasi-legitimate interest. The difficulty now is that the latest Russian actions have made it difficult for NATO to refuse membership without appearing to appease Russian bullying. Perhaps NATO membership should be offered on condition that Georgia first permit UN-supervised referendums, without the presence of Russian troops or "peacekeepers", in Abkhazia and South Ossetia to determine the future of those territories and their peoples. If that were rejected by either Georgia or Russia, and no doubt quite possibly both, then so be it. The West's position would at least have been consistent and principled.

BB: I'm afraid I see nothing principled about even contemplating bringing Georgia or Ukraine into NATO, still less about actively encouraging them to believe that membership is on offer. It should never have been offered: and Georgian or Ukrainian expressions of interest in joining should have been politely but firmly rebuffed. Georgia has paid a heavy price for its ill-conceived flirtation with NATO, and NATO's credibility has taken a nasty knock too. Georgian membership of NATO would entail a guarantee by the rest of NATO to come to Georgia's aid with military support if Georgia were ever to be attacked — and any attack could only come from Russia. Are we or the US really willing to start a third world war with Russia in defence of Georgia against its far more powerful neighbour? If not, we should stop playing games. We have dug ourselves into a nightmarish hole over this by encouraging Georgian folly with our talk of Georgian membership of NATO: we should now stop digging, not dream up fancy conditions for continuing to dig. There's anyway no need for referendums in South Ossetia or Abkhazia: the results — independence from Georgia — would be easily predictable. Making promises of military support for other countries which in the event we are quite unable or unwilling to honour — Poland and Australia come to mind — is an addictive but deeply harmful habit that we should try to shake off. Anyway, Russia is evidently on the point of recognising South Ossetia and Abkhazia as independent states, so the conditions suggested are now academic.

MH: I think … the right of independent nations to choose their friends and alliances [remains an important democratic principle], provided this choice is not a blatant act of hostility towards, or a real and demonstrable threat to the security of, any other nation. By the same token, alliances have every right to be discriminating in considering applications for membership.

BB: Of course independent nations have the theoretical 'right' that you describe. But what constitutes 'a blatant act of hostility towards, or a real and demonstrable threat to the security of, any other nation' is very much in the eye of the beholder. Few Russians would regard Georgia's accession to NATO, or the stationing of US missiles on Georgian soil, as anything else but a blatant act of hostility towards Russia and a threat to Russia's security. Do you think that the independent countries of central America or Cuba have been able in practice to 'choose their friends and alliances' without regard to what the United States has seen as a threat to its security and interests? Has the Republic of Ireland been free to exercise such a right, had it wanted to, regardless of the UK's views? Small neighbours of Big Brother have always had to work out ways to maximise their freedom of action and association without seriously antagonising Big Brother or arousing his fears. Finland has adapted to this often uncomfortable reality; so has most of Latin America. It's no kindness to the hapless Georgians to incite them to ignore it.

On Scottish secession, please see my response, above, to your original Comment, and Oliver Miles's intriguing comment immediately above this.

[1] I should have made it clear that Spain, like around 10 of the 27 member states of the EU, has not recognised Kosovo as an independent state, a decision attributed by many to its problems with Basque and Catalan separatists. There's a useful analysis here. Your turn!

Brian

I commented on a previous article about the wider Caucasus region. I have been thinking about this further and I am increasingly coming to a view that the Russian aspect of it is an unintended consequence.

Apart from some residual cold war rhetoric from the neo-cons, I cannot see any major strategic drive to embroil the USA with Russia despite some provocation from the Russian Government. I can see strategic advantage for the USA in having a friendly base in the Caucasus looking to the south east – towards Iran – particularly as the Iraqis have thwarted US intentions of long term occupation there. It follows then that the US Government's attempt to get NATO membership for Georgia is neither altruistic nor necessarily beneficial to the rest of the western allies. What appears to be a lack on the USA's part of any serious consideration of consequences from Russia or other neighbouring countries is consistent with the poor quality of analysis which has been displayed by similar White House initiatives.

I suspect therefore that this is a smoke and mirrors ploy by the US Government to establish a bridgehead in Georgia aimed at Iran not Russia; the Israeli association might be thought to reinforce this. The strategic advantages for both the USA and Israel are immense – no overflight of Arab countries by either Israeli (or US) aircraft and missiles and a very significant shortening of the distances to Tehran and the Iranian research sites as compared to what they would be from Israel.

The action by the Georgian President to take advantage of his new friends to settle domestic scores may not have entered the calculations of the White House and hence the opportunity they have given Russia to wreck an American strategy, to embarass the West by exposing the double standard vis a vis Kosovo and to reinforce the dangers of meddling on Russia's doorstep. I suspect that the implications have not gone unnoticed in Tehran hence the unusual silence from that quarter.

Brian writes: Thank you for this ingenious scenario. My main reservation is over the length of time in which the US can reasonably expect to have military and air bases in Iraq. My guess is that the Americans — or at any rate the Bush administration — intend to keep troops stationed in Iraq for a great many years, with substantial air bases to support them. Three years ago it was reported that they were planning to build four giant bases Iraq:

The same report speculated that —

A later report (2006, partially up-dated in 2008) introduces a detailed study of the issue of 'permanent' US bases in Iraq and says:

This plan depends, presumably, on the willingness of future Iraqi governments to agree to virtually permanent US bases on Iraqi soil, and in June this year (2008) the present Iraqi government was said to be resisting far-reaching US demands:

I doubt if the Americans will easily give up the neo-cons' dream scenario of an acquiescent government in Baghdad which gives Washington carte blanche to maintain a long-term military presence, with air bases, in Iraq from which to conduct operations anywhere in the middle east, including of course against neighbouring Iran: this, after all, was and presumably remains one of the principal objectives of the American invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003. US and Israeli freedom to use Iraqi airspace is obviously much more valuable to both countries than similar bases in Georgia, from which aircraft would have to fly over Turkey, Armenia or Aazerbaijan to reach Iran — not Arab states, true, but countries whose permission for military overflights in operations against the regional super-power (Iran) couldn't be taken for granted. Turkey, you will recall, although a NATO member country, rejected US requests for use of its territory or airspace for the attack on Iraq in 2003:

In 2007 it was reported that —

No doubt the Americans regard the recruitment of Georgia into the family of compliant, 'pro-western' allies in the region, ideally as a member of NATO, as a useful back-stop or insurance against the possible loss of facilities in Iraq at some future time. But their first priority must surely be to ensure, by force if necessary, that future governments in Iraq will continue to acquiesce in US bases, facilities, and overflying permission. Not only does Iraq border directly on Iran (as well as on Jordan, Syria, Turkey and Saudi Arabia), but not on Russia: Georgia has no common border with any Arab state, and has the major disadvantage of being right in Russia's back yard, and with a long history of being regarded by Russia as a vital part of its security buffer zone, never to be allowed to fall into the hands of a potential enemy of Russia. I draw the conclusion that American wooing of Georgia and sponsorship of Georgia for NATO membership are mainly designed to reduce Russian influence in its own immediate vicinity, to minimise Russia's sphere of influence, to protect the oil pipe-line that by-passes Russia, and to send a signal to Russia that even in Russia's back yard America holds the cards. Possible use of Georgia for US and/or Israeli military operations against Iran would be an additional and fairly iffy bonus: Iraq is a much better option for that. I agree that the foolish Georgian attack on South Ossetia and the violent Russian response have placed a sizeable road-block in the way of any such American ambitions regarding Georgia.

It's interesting to speculate about the likely attitude to all these American plans and ambitions of a future Obama administration. I wonder whether it would herald any radical change? All the signals suggest that a McCain administration would change very little of existing US middle east and Caucasus policies, if anything at all. They seem to me extremely scary.

I have put a copy of this exchange on Ephems as a new post, in view of the important and interesting issues discussed. Will anyone wishing to pursue the discussion with further comments please append their contributions there?

A couple of observations:

The only nations on the far side of the Polish ballistic missile interceptors from the US or UK are Ukraine and Russia. It is clearly in the wrong place to counter Iranian missiles; Turkey or at least Greece would be more useful. Ukraine is considered friendly, and Russia's ballistic missile arsenal could easily overwhelm the interceptors even if they worked perfectly. The only scenario I can see where the interceptors would be useful (assuming the work, which they won't) is if the US were to launch a massive first strike against Russia, destroying enough of its ballistic missiles to give the interceptors a good chance to prevent any reaching the US. Clearly this first strike would have to be nuclear. I believe such a strategy was considered during the Cold War, but it was expected that a few Soviet missiles would survive. Modern military satellites can IIRC track submarines by their wake.

If I'm correct then no wonder the Russians are jumpy.

Monbiot claims that the missile defence project is no more than pork for the military industrial complex. There is no such thing as a purely defensive weapon. Anything that can counter a potential enemy's deterrent allows aggression against that enemy.

I'm not aware that Russia has any issue with EU enlargement, even including the European Defence Agency. I've seen Putin quoted encouraging Ukrainian membership. Possibly this is because Russian energy exports give it leverage over the EU, especially Germany, or possibly they are only worried about the US.

Russian membership of the EU seems to be considered plausible by some European politicians and diplomats. A few years ago there was a small majority of Russians in favour, but this was before the Russian energy-backed resurgence, and I've not seen any more recent polls.

Brian writes: Thanks for that. I agree throughout. Monbiot's demolition job on the US "Son of Star Wars" missile defence system, which you quote, is also extremely convincing.

amk: "The only nations on the far side of the Polish ballistic missile interceptors from the US or UK are Ukraine and Russia. It is clearly in the wrong place to counter Iranian missiles; Turkey or at least Greece would be more useful."

Are you a member of the Flat Earth Society or have you just been looking at Mercator projection maps too much?

According to my GPS here in High Wycombe, Tehran is on a bearing of 92.53°. Warsaw is a on bearing of 78.75° (13.78° north of the track to Tehran) whereas Athens is on 118.91° (26.38° the other side of the track). Since Warsaw is somewhat closer than half way to Tehran and Athens is a bit more than half way it follows that Warsaw is quite noticeably less than half the distance from the great circle from Tehran to High Wycombe than Athens is.

Given that transatlantic flights from London start off heading well north of west (i.e., north of the continuation of the great circle from Tehran) it follows that the great circle from Tehran to North America will be north of that from Tehran to High Wycombe, presumably closer to Poland. Similarly, the track from Tehran to, say, Berlin or Hamburg will cross Poland.

Note, I’m only quibbling with your geography; I have no problem with the main points of your comment.

Ed, I’ve grabbed a globe and you’re right. Poland wouldn’t be far off the flight path of an Iran-US or Iran-UK ICBM, but eastern Turkey still looks a better bet. Russia suggested Azerbaijan. Greece would be rubbish. Apparently I’ve been conditioned by projected globes to think along latitude lines.