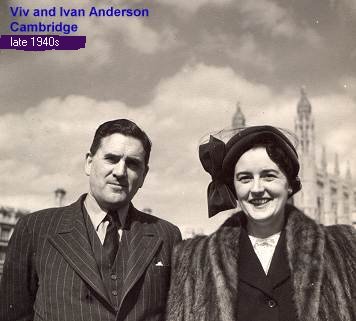

Viv Barder Anderson

Vivien Anderson, with her second husband, New Zealand-born Ivan Anderson, died in a car crash on the A 30 just outside Basingstoke in July 1950. She was 39 years old; he was 56. They were driving to their London home, 309 Carrington House, Hertford Street, from the factory in Trowbridge, Wiltshire, where they manufactured “Procea”, one of Britain’s first diet breads.

Her early death was a particular tragedy to her only child, Brian Barder. Vivien and Harry Barder had separated (and later divorced) with great bitterness when Brian was only four years old. Her relationship with Ivan, the divorced father of two daughters, had created a scandal in middle-class Bristol, and Vivien, the ‘guilty party’ in 1930s terms, had been allowed little access to her son. For most of his childhood he saw his mother for just one day in each school holiday, in his father’s house. Only when he became a teenager was he allowed to spend an annual fortnight of his summer holidays with Ivan and Vivien, and a week each at Christmas and Easter. During these sadly few holidays, Vivien was able to share with her son the life she and Ivan had built for themselves. With their Mayfair flat as a base they introduced him to their friends in the entertainment and sporting worlds of post-war London and in their yacht, “Jewel”, they took him to the Scilly Isles and to Ireland. Even her embittered first husband described Vivien as a woman of charm and beauty, and the life she led reflected this. But Brian’s limited contact with his mother meant that he knew very little about the family background which had produced her. From accessible civil and church records we have been able to construct a family tree as far as the eighteenth century but we still have very few facts about her own life before she married Harry Barder in 1933. Records show the story of her forebears on the paternal side as relatively straightforward and typical. From rural backgrounds in Dorset, Essex and Suffolk they had migrated to London in the mid-nineteenth century to become, not the working poor, but skilled or clerical middle class. Her maternal side is less straightforward and there are more gaps and some mysteries.

Her early death was a particular tragedy to her only child, Brian Barder. Vivien and Harry Barder had separated (and later divorced) with great bitterness when Brian was only four years old. Her relationship with Ivan, the divorced father of two daughters, had created a scandal in middle-class Bristol, and Vivien, the ‘guilty party’ in 1930s terms, had been allowed little access to her son. For most of his childhood he saw his mother for just one day in each school holiday, in his father’s house. Only when he became a teenager was he allowed to spend an annual fortnight of his summer holidays with Ivan and Vivien, and a week each at Christmas and Easter. During these sadly few holidays, Vivien was able to share with her son the life she and Ivan had built for themselves. With their Mayfair flat as a base they introduced him to their friends in the entertainment and sporting worlds of post-war London and in their yacht, “Jewel”, they took him to the Scilly Isles and to Ireland. Even her embittered first husband described Vivien as a woman of charm and beauty, and the life she led reflected this. But Brian’s limited contact with his mother meant that he knew very little about the family background which had produced her. From accessible civil and church records we have been able to construct a family tree as far as the eighteenth century but we still have very few facts about her own life before she married Harry Barder in 1933. Records show the story of her forebears on the paternal side as relatively straightforward and typical. From rural backgrounds in Dorset, Essex and Suffolk they had migrated to London in the mid-nineteenth century to become, not the working poor, but skilled or clerical middle class. Her maternal side is less straightforward and there are more gaps and some mysteries.

Vivien was born on 6 April 1910, the daughter of George Simon Young and his wife, Vivienne Ethel Amy (formerly Triebner), who were living at 7 Clifton Road, Ramsgate. She was named Vivien Nelsie Agatha Young, in tribute to her mother, Vivienne, and her mother’s sisters, Violet Nelsie, and Marian Agatha. She was usually known as Viv. George Young had been described as a foreman electrician when he and Vivienne married in 1908 and when Vivien was born. In 1933 when Vivien married Harry Barder she gave her father’s occupation as mining engineer and he was said to be dead. Until very recently we did not know whether Vivien was raised from infancy by a widowed mother or whether her father had died just a few weeks before her wedding. Neither did we know whether she had brothers and sisters. However in 2004 a descendant of George Young’s brother has contacted us with much family information. According to the statement on George’s marriage certificate he was already a young widower when he married Vivienne Triebner in 1908. We now know that he and Rosa Kate Louisa Rowe, born Burral, had three children, Rosetta, Laura and Harry, who were placed in an orphanage after Rosa’s death in July 1907. Presumably Vivien would not have known these half siblings. The family source revealed that, soon after Vivien’s birth, Vivienne left George, taking the baby with her. Moreover, George later had two more children, Kenneth Wyle and Louise Loretta, whose mother was born Constance Ethel Lilian Price. When Kenneth was born in Bristol in 1921, George Young gave his occupation as jobbing electrician. Far from being a dead mining engineer in 1933 George, according to his nieces and nephews, lived until 1944: they remember visiting him in Chepstow, but we do not know where he died. Neither do we know whether Vivien was aware of any of this, or whether she knew that she had two half-brothers and three half-sisters.

Brian remembered an aunt, Peggy Banks, as his mother’s sister. In fact, Peggy turned out to be Vivien’s cousin. She was Nelsie Vivien Record, daughter of Vivienne’s sister Violet Nelsie, and she married Hector Banks in 1933. (Such an uncommon name as Nelsie must have had some family significance but so far we have no clues about its provenance.) Peggy’s father, Montague Record, a master lighterman, died in 1927. Vivienne’s death certificate reveals the sad fact that she committed suicide by gas poisoning in Filton, a Bristol suburb, in 1938. She was survived by her mother, Eliza Annie Triebner, who died in 1940. Eliza’s address was 3 West Mall, Clifton, Bristol, and it was her granddaughter, Sybil Moody of the same address, who reported her death. Sybil was the daughter of the third of the Triebner girls, Marian Agatha, who had married Tyrrell Walter Moody in October 1908. It seems therefore that most of the family had moved to Bristol at some stage and Kenneth’s 1921 birth certificate shows that even George Young was living there in the 1920s, perhaps in pursuit of his errant wife. However, no family members were witnesses when Vivien married Harry Barder at the Bristol Register office in August 1933. The address she gave was 138 Fishponds Road, Bristol and the Bristol Post Office Directory lists a Dr Charles Benarmé Mora, physician and surgeon, as the householder there. Brian’s nanny, who became his father’s housekeeper, had sometimes mentioned Dr Mora as Vivien’s uncle, and Brian had assumed that there was some kind of relationship, but I have not found any family link. Mother and daughter, Vivienne and Vivien, were listed at 138 Fishponds Road on the 1933 electoral register and a likely explanation is that Vivienne was Dr Mora’s housekeeper. Although he had qualified as a doctor in London in 1908 Carlos Mora seems to have been born abroad and this is presumably why he does not appear on the Bristol electoral register. Like many of the Triebner family connections, he seems to have had a chequered marital career: by 1933 he was possibly already separated from Celia Buttgenbach, his first wife, who lived in London. After her death he married twice more. Whether deliberately contrived or not, this confusion about family relationship follows a Triebner family pattern. We shall probably never know where Vivien spent her youth after her birth in Thanet, nor where she was educated. Brian believes that she was a secretary before her marriage and this is confirmed by Ivan Anderson’s daughter, Triska, who understood that her father’s second wife was “a high-powered secretary”. She was certainly competent with a type-writer.

George Young and Vivienne Triebner married in the Thanet Register Office in November 1908. It seems that George was living in Ramsgate with his younger brother, Frank Andrews Young. They worked as electricians and are said to have installed Ramsgate’s first sea-front lights and an illuminated fountain. It was there that Rosa had died and her children were in a Thanet orphanage. Frank and his future wife, Maggie Violet Slaven, were witnesses to George and Vivienne’s wedding. Although Vivienne’s mother, Mrs Triebner, was listed as a householder at 91 Hardres Street, Ramsgate in 1909, a near neighbour of the Slaven family, she was only there for that one year and we do not know what took her there. By 1913, when her last unmarried daughter, Violet, married Montague Record at the Hampstead Register office, Mrs Annie Triebner was listed in the London Directory as the householder at 27 Downshire Hill, Hampstead. In1910, George appeared in the Ramsgate directory as the householder at 7 Clifton Road, the address on Vivien’s birth certificate.

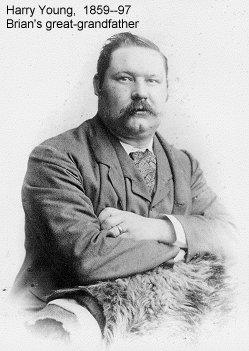

George had been born on 27 October 1880 and named George Simon after his grandparents, George Young and Simon Andrews. George’s parents, Harry Young and Rosetta Sarah Andrews, were married at Holy Trinity Church, Haverstock Hill, on 16 May 1880, only five months before George’s birth. Both gave their address as 60 Harmood Street, Kentish Town. This was Rosetta’s parents’ home, and the likelihood is that Harry had been a lodger, attracted by the landlord’s young daughter. She was only 18 when she married; Harry was 21. In the 1881 census the Youngs, with baby George Simon, were living at 54 Dale Road, Kentish Town, not far from Harmood Street. Harry had been described as a railway clerk on his marriage certificate and in the census he gave his occupation as accountant: presumably he was in the railway accounts department. Dale Road still exists as a small cul-de-sac leading to a mass of railway lines. Kentish Town was one of those many areas of London whose geography was changed by the building of railways. Three main lines pass through Kentish Town on their way to King’s Cross, Euston and St Pancras. Harmood Street is mentioned by Gillian Tindall in her history of Kentish Town, The Fields Beneath, as one of the first developments off the Chalk Farm Road (Pancras Vale). It was built in the 1830s. “The houses in it were – and are – extremely small, the two-up, two-down-and-a-wash-house variety, with tiny back gardens.” She describes the way the population of the street changed “not dramatically but significantly” from middle class to working class in successive censuses from 1841 to 1861: “evidently Harmood Street was a place for people on the way up??or the way down”. (In the year 2000, it was definitely on the way up: these small terraced houses selling for nearly half a million pounds each.) Gillian Tindall also noticed that the numbers of people living in each of these small houses were rising, shared by more than one family or housing lodgers. Unfortunately when she wrote, in 1977, the censuses from 1871 and 1881 had not been made accessible to public search.

George had been born on 27 October 1880 and named George Simon after his grandparents, George Young and Simon Andrews. George’s parents, Harry Young and Rosetta Sarah Andrews, were married at Holy Trinity Church, Haverstock Hill, on 16 May 1880, only five months before George’s birth. Both gave their address as 60 Harmood Street, Kentish Town. This was Rosetta’s parents’ home, and the likelihood is that Harry had been a lodger, attracted by the landlord’s young daughter. She was only 18 when she married; Harry was 21. In the 1881 census the Youngs, with baby George Simon, were living at 54 Dale Road, Kentish Town, not far from Harmood Street. Harry had been described as a railway clerk on his marriage certificate and in the census he gave his occupation as accountant: presumably he was in the railway accounts department. Dale Road still exists as a small cul-de-sac leading to a mass of railway lines. Kentish Town was one of those many areas of London whose geography was changed by the building of railways. Three main lines pass through Kentish Town on their way to King’s Cross, Euston and St Pancras. Harmood Street is mentioned by Gillian Tindall in her history of Kentish Town, The Fields Beneath, as one of the first developments off the Chalk Farm Road (Pancras Vale). It was built in the 1830s. “The houses in it were – and are – extremely small, the two-up, two-down-and-a-wash-house variety, with tiny back gardens.” She describes the way the population of the street changed “not dramatically but significantly” from middle class to working class in successive censuses from 1841 to 1861: “evidently Harmood Street was a place for people on the way up??or the way down”. (In the year 2000, it was definitely on the way up: these small terraced houses selling for nearly half a million pounds each.) Gillian Tindall also noticed that the numbers of people living in each of these small houses were rising, shared by more than one family or housing lodgers. Unfortunately when she wrote, in 1977, the censuses from 1871 and 1881 had not been made accessible to public search.

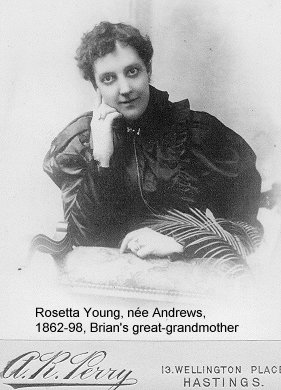

Simon Andrews was probably on the way up in 1881, although in the 1881 census a lodger, working as a tarpaulin sheet maker, and another family with an 8-year-old daughter, shared 60 Harmood Street with Simon, his wife Emma, and their 2-year-old grandson. In 1881, Simon was a civil servant (Inspector of Telegraphs). On his daughter’s marriage certificate in 1880 he had been described as a telegraph engineer. He was born in January 1840 in Laxfield, Suffolk, a village east of Southwold, north of Framlingham. His family was listed in the 1851 census living at Town Houses, Laxfield. Robert, his father, was an agricultural labourer and Simon was one of seven children living at home. Another Andrews family, 60-year-old Simon, and his 50-year-old wife, Rebecca, both agricultural labourers, also lived in Laxfield, too young to be the grandparents: but Simon may have been Robert’s older brother. Simon and Emma Woods were married in July 1860 in St Saviours, South Hampstead. Simon lived in St Pancras, Emma in South Hampstead: their marriage certificate reveals no further details about their addresses. Simon was a porter, perhaps at one of the many mainline railway terminals. He must have been both bright and ambitious to have reached such a middle-class occupation by 1881, even if he might have exaggerated his status on official documents. Emma too seems to have come from an upwardly mobile family. Her father, George Woods, was also an agricultural labourer in the 1851 census. They lived in Church Street, Chrishall, Essex, near Saffron Walden. The 1851 census shows Emma as 17 years old, thus six years older than Simon, although in the 1881 census she declared herself to be a year younger than her husband. Young grooms and brides of uncertain age are a recurring theme in Vivien’s family tree. Emma was the oldest of six children living at home in the 1851 census, all born in Chrishall. Her brother, another George Woods, appears in the 1881 census living in Tottenham. He was also a civil servant, a “Battery Department clerk”, apparently a section of the telegraph department. His unmarried brother-in-law, Edward Walters, was living with the family and he too was a Battery Department clerk. Emma might have been living with her brother when she married. The George Woods who witnessed her wedding is more likely to have been her brother than her father making the journey from Chrishall. For the birth of her daughter, however, Emma returned to Chrishall and Rosetta was born there in 1862, a second child for Simon and Emma. Their son, Robert, was born in Pancras in 1860 when Simon was still working as a railway porter. But by 1862 he was already starting to better himself and on his daughter’s birth certificate he is shown as a railway telegraph clerk. It might be that Richard Garret’s ironworks at Leiston and Ransome’s of Ipswich, Suffolk, firms which led the way in the manufacture of agricultural machinery in the mid-nineteenth century, not only deprived farm-workers of employment and led to large-scale migration, but also inspired a local boy to work with modern machines. The 1881 census shows that Simon’s older brother, William, had remained in Suffolk as a farm worker: one of his sisters, Eliza, married a blacksmith and lived in Lowestoft; the other, Sarah Ann, was married to a Suffolk farm bailiff. In 1972 Ronald Blythe collected the reminiscences of villagers in an area which seems to have been very close to Laxfield and published them in the famous book Akenfield, the disguised name of the real village. These accounts of village life at the turn of the century vividly describe the life which Simon would have led had he remained a Suffolk villager. Instead, as our recent information tells us, before he died in 1904 he had become a Conservative Councillor in Camberwell.

Rosetta’s husband, Harry Young, came of rural stock, but his family had already made the transition from agricultural labouring to artisan status before June 1859 when he was born in Bell Street, Shaftesbury, Dorset. According to his birth certificate his father, George Young, was a tailor and had been so when he married Mary White in the parish church of Shaston St James in July 1854. Shaston seems to be a village within the Shaftesbury district and both gave it as their sole address. Their fathers, John Young and William White, were carpenters. George Young, according to 1881 census returns, was born in Wyle, Wiltshire and was baptised there on 26 October 1833, son of John Young and Hannah Wilmot who had married in 1828. Mary White, again according to the census record, was born in Shaftesbury and was 10 years older than her husband. A year after Harry’s birth the 1861 census shows George Young as victualler at the Grosvenor Arms Tap and so too in 1871. In 1881 he was described as an inn-keeper in Shaftesbury High Street and the 1880 Dorset Trade Directory lists him as the licensee of The Rose and Crown in Shaftesbury High Street. There is no longer a Rose and Crown in Shaftesbury and the 1881 Shaftesbury census does not give street numbers. But the juxtaposition of side streets in George Young’s section of the census suggest that his inn was at the main centre of the High Street, close to Gold Hill, later made famous in the Hovis advertisements. Haverstock and Highgate Hills can have presented no problems to Harry who must have climbed Gold Hill daily. In 1890, apparently on his retirement, George Young made his last will. Mary, his wife, had died in 1888 and he left all his household effects, plate, linen, pictures, furniture, pianoforte, and a monetary legacy to his unmarried daughter, Emily, born in 1863. His oldest son, Frederick William Young, took over his occupation as innkeeper and the residue of his estate was to be divided between his four children, Frederick, Harry, Laura, (already married to Sylvester Wright), and Emily. There was a slight hint of worry in George’s proviso that any liabilities incurred by him and outstanding at the time of his death on behalf of Harry or Sylvester, should be satisfied before the estate was divided. But perhaps that was just lawyer talk. George Young died in 1896.

status before June 1859 when he was born in Bell Street, Shaftesbury, Dorset. According to his birth certificate his father, George Young, was a tailor and had been so when he married Mary White in the parish church of Shaston St James in July 1854. Shaston seems to be a village within the Shaftesbury district and both gave it as their sole address. Their fathers, John Young and William White, were carpenters. George Young, according to 1881 census returns, was born in Wyle, Wiltshire and was baptised there on 26 October 1833, son of John Young and Hannah Wilmot who had married in 1828. Mary White, again according to the census record, was born in Shaftesbury and was 10 years older than her husband. A year after Harry’s birth the 1861 census shows George Young as victualler at the Grosvenor Arms Tap and so too in 1871. In 1881 he was described as an inn-keeper in Shaftesbury High Street and the 1880 Dorset Trade Directory lists him as the licensee of The Rose and Crown in Shaftesbury High Street. There is no longer a Rose and Crown in Shaftesbury and the 1881 Shaftesbury census does not give street numbers. But the juxtaposition of side streets in George Young’s section of the census suggest that his inn was at the main centre of the High Street, close to Gold Hill, later made famous in the Hovis advertisements. Haverstock and Highgate Hills can have presented no problems to Harry who must have climbed Gold Hill daily. In 1890, apparently on his retirement, George Young made his last will. Mary, his wife, had died in 1888 and he left all his household effects, plate, linen, pictures, furniture, pianoforte, and a monetary legacy to his unmarried daughter, Emily, born in 1863. His oldest son, Frederick William Young, took over his occupation as innkeeper and the residue of his estate was to be divided between his four children, Frederick, Harry, Laura, (already married to Sylvester Wright), and Emily. There was a slight hint of worry in George’s proviso that any liabilities incurred by him and outstanding at the time of his death on behalf of Harry or Sylvester, should be satisfied before the estate was divided. But perhaps that was just lawyer talk. George Young died in 1896.

Harry, who, with his brother Frederick, had been educated at Christ’s Hospital School, did not remain a railway clerk for long. When his and Rosetta’s fourth child, Frank Andrews Young, was born in 1887 Harry was a beer retailer at The Roan House, Pollard Street, Bethnal Green. All told they had nine children, of whom one died in infancy, before Harry died in 1897. At the time of his death he was the licensee of The Hanbury Arms in Linton Street, Islington. George, the oldest of the nine orphans, was still only 16 years old. Rosetta, their widowed mother, married Frederick Ernest Spraggons just a few months later in February 1898 but she tragically died within a month of this marriage, leaving Frederick in charge of the Hanbury Arms and the eight children. Emily Young, still unmarried in Shaftesbury, took over the upbringing of Rosetta’s six year old daughter, another Rosetta always known as Rose. She too remained single and as Aunt Rose became the family memory bank. In old age she recorded a tape on which she said that she believed that her grandfather,  Simon Andrews, persuaded her mother, Rosetta, to marry Frederick Spraggons because he felt that she needed support with her large family. Sadly, Rosetta’s only brother, Robert Andrews, who might have been expected to help his sister with her burdens, had accepted a job opportunity in South Africa and had died there of fever with his infant sons in 1888. Conscientiously striving Simon must have been very anxious for his widowed daughter and it is certainly true that he had confidence in Spraggons who was appointed trustee of Simon’s estate when he died in 1904. Unfortunately within a few years Frederick was declared bankrupt and the children lost their inheritance from Councillor Andrews, their grandfather. Nevertheless the elderly Rose remembered Frederick without rancour. He in turn had remarried in 1899 and the children acquired a young step-mother in Clara Livings. The Livings family of Clavering, Essex, were kin to Emma Andrews through her mother, Joyce Chipperfield, who was born in Clavering, and they, along with Emily and, eventually, Rose in Shaftesbury, seem to have provided comfort and refuge to successive generations of the Young family. George had left the Hanbury Arms soon after his mother’s death and was living in Camberwell with Rose Rowe for the 1901 census, and it seems that Frank Andrew Young, only 10 when his father died, ran away from his step-parents to join his older brother and to work as an electrician with him. However, family ties seem to have remained strong and regular bulletins passed between the Shaftesbury and Clavering branches.

Simon Andrews, persuaded her mother, Rosetta, to marry Frederick Spraggons because he felt that she needed support with her large family. Sadly, Rosetta’s only brother, Robert Andrews, who might have been expected to help his sister with her burdens, had accepted a job opportunity in South Africa and had died there of fever with his infant sons in 1888. Conscientiously striving Simon must have been very anxious for his widowed daughter and it is certainly true that he had confidence in Spraggons who was appointed trustee of Simon’s estate when he died in 1904. Unfortunately within a few years Frederick was declared bankrupt and the children lost their inheritance from Councillor Andrews, their grandfather. Nevertheless the elderly Rose remembered Frederick without rancour. He in turn had remarried in 1899 and the children acquired a young step-mother in Clara Livings. The Livings family of Clavering, Essex, were kin to Emma Andrews through her mother, Joyce Chipperfield, who was born in Clavering, and they, along with Emily and, eventually, Rose in Shaftesbury, seem to have provided comfort and refuge to successive generations of the Young family. George had left the Hanbury Arms soon after his mother’s death and was living in Camberwell with Rose Rowe for the 1901 census, and it seems that Frank Andrew Young, only 10 when his father died, ran away from his step-parents to join his older brother and to work as an electrician with him. However, family ties seem to have remained strong and regular bulletins passed between the Shaftesbury and Clavering branches.

Vivienne Triebner, so briefly part of this family, was the daughter of Frederick Charles Triebner and Eliza Annie Quartly, who had married at St Ann’s Church, Tottenham, on 8 May 1885. Their first child, Violet Nelsie, was born in December 1886. Vivienne was born a year later on 26 December 1887 at 5 Ippleton Road, Edmonton, and a younger sister, Agatha Marian, was born in March 1890. Frederick and his father, another Frederick Charles, both described themselves as mariners on their marriage certificates. Neither pursued this profession for very long. Frederick Charles the father had been a commercial traveller for some years before he had died in 1878 at the age of 32. The younger Frederick Charles had become a furrier by 1887 when Vivienne was born. In contrast, Eliza’s father, William Benjamin Quartly, spent nearly 40 years working at his craft as an engraver on wood.

The national index for the 1881 census shows that the majority of Quartly or Quartley families lived in Devon and Somerset. The first of Vivien’s Quartly ancestors to live in London was John Quartly who married Mary Ann Sears at St Matthew’s Church, Bethnal Green, on 2 September 1809. John and Mary Ann’s son, William James Quartly, was born in Paul Street and baptised at St Leonard’s Church, Shoreditch on 17 March 1811. The next family record is in Lambeth. In August 1817 John Sears Quartly, son of John and Mary Anne, was baptised in St Mary’s Lambeth, followed by Francis Cox Quartly in 1820 and Mary Anne in 1823. At that time the family lived in Lambeth High Street and John was a jeweller. He died in 1828 and information from his will establishes him as the John Quartly who was born in South Molton, Devon in 1787, son of another John Quartly and Phillipa Hele who had married in 1784. Phillipa apparently owned property in South Molton which was the main substance of the will. By 1828 John was apparently running his jewellery business in Woodstock Street, off Oxford Street: it is presumably just a coincidence that It runs off South Molton Street.

William James Quartly, John’s oldest son, returned to his birthplace to find a bride. He was married in March 1839 at his baptismal church, St Leonard’s Shoreditch, to Mary Ann Wrigglesworth. He was said to be “of full age” and we know that he was 28 years old. She was described as a minor and the 1851 census places her date of birth as around 1819. Unlike most brides in those days she is credited with an occupation, a dressmaker. Her father, who was dead, had been a stone mason. William lived in Britannia Street, Hoxton, and was a brass founder. After the wedding William and Mary Ann moved in with her widowed mother, Elizabeth Wrigglesworth, who lived at 56 Hoxton Square. According to the 1841 census Elizabeth Wrigglesworth was a greengrocer and William Quartly had become a draper. Mary Ann, no longer a dressmaker, was the mother of William Benjamin Quartly, Vivien Barder’s great-grandfather, who was then one year old. Fifteen-year-old Emma Wrigglesworth, presumably Mary Ann’s younger sister, completed the household. By the time of the 1851 census a new family occupied 56 Hoxton Square.

The 1841 census did not list birthplaces, and ages were rounded up and down within 5 years. So it is not very informative about Elizabeth Wrigglesworth, William James’s mother-in-law. She was said to be 55 years old. The national index of the 1881 census shows the vast majority of Wrigglesworths as having been born in Yorkshire and most of them still lived there in 1881. The deceased stone mason, with an indecipherable first name, had presumably migrated southwards around the time that John Quartly had come to London. Later in the nineteenth century Charles Booth described Hoxton as one of the most “crime ridden and pestilential” areas of the metropolis. It is a reputation which is only now beginning to fade as Hoxton Square is optimistically proclaimed by the Sunday supplements as an artistic centre with a vivid café society. However in the late eighteenth century and the early years of the nineteenth century it was an agreeable place for a skilled stonemason to live and work. A study by Christopher Miele published by the Hackney Society in 1993 states that in “the first three decades of the nineteenth century, Hoxton enjoyed life as a polite suburb. Middle-class development was concentrated around Hoxton and Charles Squares and Aske’s Hospital.” Elizabethan laws restricting building around the City of London had preserved Hoxton’s rural character for centuries and development was sedate until the completion of the Grand Union Canal in 1814 attracted industry into the area. Hoxton Square was first laid out in the late seventeenth century and until the early nineteenth century was best known for the Dissenting Academy established there in 1699. Number 56, home to the Quartlys, had been built early in the nineteenth century and is one of the few surviving reminders of the Square at that time. It is described thus by Christopher Miele:

?.a more or less intact early nineteenth century house. The ground floor was converted to a shop in the 1820s or 1830s, to judge by the style of the front. The broad sign fascia, flat modilioned cornice, and brackets flanking the entrance and on the right party wall are an original design. The shallow bowed shop front, although somewhat rebuilt in the twentieth century, is a common late Georgian or Regency type.

It could well have been converted to a shop for Elizabeth Wrigglesworth’s greengrocery. Now it is a minicab office, shabby on the outside and with a typically plywood partitioned interior. But it is still possible to visualise it as the kind of shop which black-and-white Hollywood constructed on its back lots for English period dramas.

William James Quartly was still a brass founder when William Benjamin was born at 56 Hoxton Square on 29 March 1840. He had become a draper by June 1841 when the census was taken and was described as a woollen draper on William Benjamin’s 1859 marriage certificate. He and Mary Ann, formerly Wrigglesworth, had three other children in Hoxton, Hannah, who was baptised at St Leonards in 1844, Isaac born around 1844 and Edwin born around 1845. The family was listed in the 1851 St Pancras census at 21 Frederick Street, which runs between Grays Inn Road and Kings Cross Road. Other householders in the road were carvers and gilders, brush makers, woodcutters. William was still a woollen draper, but it is perhaps significant that his children grew up with craftsmen. The last documentary record we have of William James Quartly is the 1881 census. Mary Ann was dead and he was living alone at 62 Maroon Street, Limehouse, where his neighbours were small businessmen and craftsmen, some working in the river trades. He must have been reasonably prosperous in business because he was an annuitant: in the days before state pensions he had managed to provide a retirement income for himself.

His son, William Benjamin Quartly, Vivien Barder’s great-grandfather, married Cecilia Ryan at St Pancras Church in July 1859. Both were said to be “of full age”, and we know that he was 19 years old. His address was Exmouth Street, possibly surviving now as Exmouth Mews, between North Gower Street and Euston Station. Cecilia’s address on her marriage certificate was Chalton Street, the other side of Euston Station, but the 1851 census shows the Ryan family as living in Exmouth Street. Cecilia’s father, Joseph, was a 42-year-old plumber, one of the many Irish-born Ryans living in St Pancras at that time. He had died by the time his daughter married, thus dead before he had reached 50 years. His wife, Mary, born in Lancashire, was also said to be 42 in 1851. Cecilia was the third of their six children, all born in St Pancras. According to this 1851 census, Cecilia was 16 years old, thus five years older than William, and she was working as a servant.

When he married in 1859 William Benjamin was an engraver on wood. He was so described on his children’s birth and marriage certificates and in all censuses right up till 1901 when he was 63 and still working as a wood engraver. Gillian Tindall, in her Kentish Town history, already mentioned, found a number of engravers in her census searches and described engraving as a genteel form of sweated labour. In addition, she described an influx of pianoforte makers and engravers, among others, in the 1850s, as bringing the industrial proletariat to Kentish Town. However, until the invention of the photogravure process towards the end of the nineteenth century, engraving by highly skilled craftsmen was the way in which illustrations of events, or artistic paintings, could be brought to a wide audience, in the new daily presses, magazines, or engravings sold for display. Towards the end of the nineteenth century the skill began to be superseded by new technique but there is a recent interest in the work and identity of the individual engravers who brought the work of artists to the public and whose contributions have passed largely unnoticed. One result of such an interest is a Dictionary of Victorian Wood Engravers‘ by Rodney K Egen, published in 1985 by Chadwick and Healey. Harry James Quartly and Alfred Quartly, two of William Benjamin’s sons, are listed in this work . Harry continued to appear as a wood engraver in the London Directory as late as 1913. By that time his work was almost certainly an artistic enterprise rather than an attempt to compete with modern printing processes. Also listed in the Egen Directory are FW Quartley, who went to New York in 1852, and his brother John Arthur Quartley, who spent some time working in France and, in 1845, married in the British Embassy in Paris. Work attributed to these men appears in the catalogues of London and New York museums. The coincidence of relatively unusual names and occupations would suggest a relationship with William Benjamin Quartly, wood engraver, but no such relationship can be established.

William and Cecilia Quartly’s first child was Cecilia Mary Ann, born on 29 April 1860 and baptised at St Pancras Old Church in July that year. The family address was then 5 Dukes Road, St Pancras, on the Bloomsbury side of the Euston Road. In the census, taken in April 1861, they had moved to 35 Mecklenburgh Street between Grays Inn Road and Corams Fields. A son, William Edwin Quartly, was born in March 1864 and baptised at St Pancras Old Church in the July. By then the family was living at 14 Melton Street, St Pancras, in the shadow of Euston Station. According to the age given on her marriage certificate, Eliza Annie, Vivien’s grandmother, should have been the Quartly child born in 1864. I have not found any record of her birth but in the 1871 census when the family was living at 4 Jeffrey’s Street, Kentish Town, she was 9 years old, a year younger than Cecilia Mary and therefore born around 1862. The William Edwin born in 1864 had died after a few months and another baby had been given the name William in 1869. For the 1881 census, the Quartlys were living at The Cottage, Upper Park Hill, Hampstead, just up from Belsize Park, William Benjamin was an engraver on wood and the oldest son, Alfred, was an apprentice engraver. (Neither Eliza Annie nor her older sister, Cecilia, were at home on census night, or perhaps the enumerator missed them when he transferred the family’s details to his final record.) There were many thousands of other Londoners who, like the Quartlys, were constantly on the move during these years, searching for a permanent, affordable, home. Sometimes the reasons were changes in their own economic or family circumstances. Sometimes the reason was the demolition and reconstruction of whole areas, often because of railway development. Gillian Tindall quotes Lord Derby speaking in Parliament in 1861:

“The Poor are displaced, but they are not removed, they are shovelled out of one side of the parish only to render still more over-crowded the stifling apartments on another side”.

By 1885 the Quartlys, continuing their northward migration from inner London, had arrived in Tottenham, which in the 1880s was one of the four fastest growing towns in England. The building of the Great Eastern Railway had attracted speculators who built thousands of terraced houses for the artisans and skilled workers who could afford to commute from these new houses because of the passing of the Cheap Fares Act in 1864.

Eliza Annie’s address when she married Frederick Charles Triebner in May 1885 was 25 Westerfield Road, Tottenham. Frederick lived nearby at 26 Russell Road. It is possible that it was not only propinquity which brought them together. The 1891 Tottenham census shows William and Cecilia Quartly living at 6 Francis Villas, Hermitage Road, while Eliza and her husband lived around the corner at 3 Florence Villas, St Ann’s Road. One of the unmarried Quartly sons was working as a furrier’s clerk. Although for this census Frederick Triebner’s occupation was given as commercial traveller, he had already attempted his eventual lifelong business career as a furrier: this was his stated occupation on Vivienne’s 1887 birth certificate. Perhaps, therefore, Eliza met Frederick Triebner as a friend of one of her brothers. As so often in this family history, Eliza was older than her husband. On her marriage certificate she admitted to being two years older than the 19-year-old Frederick but the evidence of the 1871 census is that she was around four years older than him.

As already mentioned, in his brief adult career as a mariner, before he became a furrier, Frederick Charles Triebner was following in the footsteps of his father, another Frederick Charles. Although the older Frederick had been described as a mariner (deceased) on his son’s marriage certificate, he had already left the service some years before his death in 1878. Frederick Charles Triebner, the father, was a Midshipman, Merchant Service, when at the age of 21 he married Fanny Mary Russell in the Catholic Church of St John the Evangelist, Islington, in June 1866. But when Frederick junior was born seven months later on 15 January 1867 at 16 Hungerford Road, West Holloway, his father, who registered the birth, was described as a “late midshipman”. This unfortunate phrase was sadly prophetic because Frederick, aged 32, died of pulmonary exhaustion and TB in May 1878. When he died he was a commercial traveller, his occupation when he registered the birth of another son, Edgar Ellis, born in June 1870 at 9 Bird’s Terrace, Islington. A daughter, Marian Agatha (names given in reverse to her niece who was born in 1890), was born in St Pancras in March 1869 and another daughter, Rosa Agnes, was born and died at 13 Russell Road in April 1972. Frederick and Fanny Triebner were on the move throughout their brief married life, with a different address for each birth and for Frederick’s death: he died at 4 Ester Road, Islington. Unfortunately they were not living at any of these addresses for the 1871 census which might have provided an answer to some questions about the family. In the 1881 census, the widowed Fanny was living at 150 Corbyn Road, Holloway, but only Edgar and Marian were at home with her. Frederick junior, aged 14, was presumably at a training school or already at sea. Strangely, in the 1891 census already mentioned, where Frederick Charles unusually named himself as Charles F Triebner, he gave his birthplace as Peckham, although we know from his birth certificate that he was born in West Holloway. He still insisted on Peckham in the 1901 census.

Fanny was described as an annuitant in the 1881 census and, whatever her income, the fact that Frederick, only 11 when his father died, was provided for in either the Royal or the Merchant Navy must have been a help to her budget. She gave her age as 34 on the census form, which would have meant that she was born in 1847. When she married she gave her age as 23, therefore born in 1843 and two years older than her 21-year-old husband. In fact she was born Fanny Mary Dickensen [sic] Russell on 27 December 1838 and, at 28, she was seven years older than Frederick. There is something of the shot-gun wedding about this marriage of a pregnant older lady to the young midshipman, witnessed (somewhat unconventionally for the age) by two women, Fanny’s mother and sister. Indeed the circumstances of this wedding are among the mysteries of the Triebner family. Frederick was the son of Timothy Frederick Triebner, described on Frederick’s June 1866 marriage certificate as deceased. But Timothy had married another of Fanny’s sisters, Rosa Flower Russell, as his second wife at Westminster Register Office in January 1866 and he was alive and well until 1876 when he died in Bristol. It seems unlikely that the Russells really believed that Timothy had died in the six months since he had married their daughter. A possible explanation is that Frederick was not yet 21 and that, given Fanny’s pregnancy, the Russells were not prepared to wait for Timothy’s permission for his son’s marriage.

When Fanny was born at 6 Walcot Buildings, Bath, her father, John Frederick Russell, was a schoolmaster. Her mother was Emily Goodall Russell, formerly Atkins. The Russells were still living in Walcot Buildings for the 1841 census with five children, including Rosa and Fanny. By the time of the1851 census they had moved to 30 Thomas Street, Walcot, Bath. They may have been running a school in their home, because not only was John still a schoolmaster but Emily also was described as a schoolmistress. They had produced three more sons. Two of the facts that Brian thought that he knew about his mother’s family were that they were Catholics (his mother at least lapsed) and that they came from the west country. Fanny Russell’s Catholic marriage is the only evidence of Catholicism in the family records, but both the Youngs and the Quartlys, as well as the Russells, had west country roots. Although the 1851 census shows both John and Emily as born in Bath, I have not found baptismal or marriage details for either of them in accessible Anglican records. This supports the belief that they were Catholics.

John Frederick Russell appeared in the Bath Directory as a schoolmaster only until 1852. After that date the only records I can find for him show him as living apart from his family. In the 1881 census, aged 71, he was living and working as a tutor in a boarding school in Brighton. By 1891 he was a boarder in a lodging house in Islington and the following year he died in the Edmonton Workhouse. Presumably there had been some family disaster in the 1850s but his sons and daughters went on describing him on their marriage certificates variously as Professor of Classics, Gentleman, Schoolmaster, Of Independent Means. Mrs Russell was listed in the London Directory as the householder at 11 Bartholomew Road in 1866. This was the address given by Rosa Russell for her 1866 wedding to Timothy Frederick Triebner and also the address given by both Frederick Charles Triebner and Fanny Russell when they married a few months later. The 1871 census shows Emily Russell, living in Park Road Villas, Upper Holloway, head of a household which included her unmarried daughter, another Emily, and a married son, Alfred, with a wife and two children. Alfred described himself as a heraldic artist. Charles, another of the Russell sons, was also a heraldic artist when his daughter was born in 1872. In 1881 Emily Russell was listed as an annuitant and the head of the household at 23 Sparsholt Road, Islington, just around the corner from her widowed daughter, Fanny Triebner. The 1878 London Directory shows Alfred Russell as the householder at this address, but he and his family had moved by1881. Emily’s household consisted of three adult children: Emily, aged 42, an unmarried governess, William and Charles. William was married and Charles was a widower. There were seven Russell grandchildren living in the house, three born in Middlesex, and four in Devonport. The oldest of the Middlesex-born children was 10, so at least one part of the Russell family had moved to London around 1861. Emily had a 14-year-old servant to help with her large family, and with whatever responsibilities she assumed for Fanny and her children. It was Emily, mother-in-law, who was “present at the death” of Frederick Charles Triebner in 1878 and who reported the death to the Registrar.

Emily’s responsibilities for Fanny and her children, as well as her other family, must have loomed large because although Fredrick Charles was one of the twelve, possibly thirteen, children of Timothy Frederick Triebner he was almost certainly one of the three, possibly four, illegitimate children fathered by Timothy. We have no evidence that the legitimate and illegitimate families had any contact with each other.

Timothy Frederick Triebner was born in Holbeck, Yorkshire in 1807, son of Timothy Traugott Triebner. All the Triebners in English nineteenth- and twentieth-century records are descended from Timothy Traugott Triebner through Timothy Frederick, his only son. As Timothy Triebner, “gentleman of this parish”, he married Betty Rhodes, spinster, in St Peter’s Church, Leeds on 17 January 1803 and their marriage certificate is the first appearance of a Triebner in English records. Timothy Traugott had been born in December 1777 in Ebenezer, a German Lutheran settlement in the British Colony of Georgia, North America. Timothy’s father, Christopher Frederick Triebner, was one of the two pastors in Ebenezer. He had been born in Poessneck, Germany, in 1740 and, after education at Halle University had taken up his position in 1769. Ebenezer and, indeed the colony of Georgia itself, had been founded just over thirty years earlier in 1734. Lutherans expelled from Salzburg by a Roman Catholic Archbishop had been sponsored by the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK) to make the hazardous journey to a new colony which guaranteed religious freedom. One of the two pastors who travelled with the first settlers was Israel Christian Gronau, also educated at Halle University. Soon after Christopher Frederick arrived in Ebenezer, he married Gronau’s daughter, Frederica Maria. Thus Timothy Traugott Triebner was both son and grandson of pastors and was descended from the earliest of Georgia’s settlers. During the American War of Independence, Christopher Frederick Triebner played a very active role in support of the British crown and left Ebenezer with his wife and three children as refugees at the end of the war. The family spent some time in Florida and then in the Bahamas before reaching England. Christopher Frederick was granted a pension by the SPCK and also received compensation from the British Government for the loss of lands, property, land and slaves. Once in England he pursued an active career as a pamphleteer and preacher, first in London and then in Hull where he preached to Germans employed in the sugar refining industry.

One of his two sons, another Christopher Fredrick, returned to Georgia around 1802 and had been appointed as a judge before his early death in 1815. Timothy Traugott remained in England and established himself as a successful businessman. He had interests in the Leeds Liverpool Canal and tobacco imports, suggesting a continued link with the Americas. Betty Rhodes, his wife , came from a prosperous Leeds family of wool merchants who also had business interests in the United States.

Timothy and Betty Triebner had three children who were each baptised at Holbeck Parish Church, Yorkshire: Timothy Frederick in July 1807, Maria Ann in January 1809 and Elizabeth in December 1811.

Like his father, Timothy Frederick Triebner, traveller (ie commercial traveller), married at St Peter’s Church, Leeds. The date was 20 October 1829 and his bride was Harriet Elizabeth Fownes, spinster of Camberwell. Like so many brides in this family story, Harriet was older than her groom. She was born on 18 May 1803 and baptised Harriott (sic) Elizabeth at St Saviours, Southwark in June 1803. St Saviours, after centuries of existence, was enlarged to become Southwark Cathedral in 1897 when it was decided to create a diocese to serve the growing population south of the River Thames. Harriet’s parents were Gilbert Jellians Fownes of the parish of St Saviour’s and Ann Woodcock, of the parish of St Mary Magdalen, Bermondsey. They married, by licence, at St Saviour’s on 29 September 1798: Ann Woodcock’s signature in the St Saviour’s marriage register is in a particularly elegant hand. Their first child, another Gilbert Jellians, was baptised at St Saviour’s in August 1799. According to his children’s baptism records Gilbert Jellians, the father, was a furrier. The London Directory of 1790 lists a John Fownes of 15 White Street, the Borough as a furrier. He might have been Gilbert’s father. Vivien’s grandfather, the younger Frederick Charles Triebner, became a furrier and she married into the Barder family of furriers, but this is by far the earliest mention of furriers in the family. Stephen Inwood in his 1998 History of London mentions that in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries Baltic commodities, including furs, were a major element in London’s commerce and that in 1770 the leather and fur industry was England’s second most valuable industry and largely centred on Bermondsey and Southwark. He notes that the Baltic trade was dominated by German, Hanseatic, merchants, and it is reasonable to speculate that it was this trading which brought Triebners and Fowneses together, although it is surprising that Harriet of Camberwell journeyed to Leeds to marry rather than her groom joining her in Southwark. Their first child, another Harriet Elizabeth, was baptised at St Peter’s, Liverpool on 30 August 1830. Their move from Yorkshire to Liverpool soon after their marriage could have been for trading purposes, such as Timothy’s interest in the Leeds Liverpool Canal, or perhaps because of family connections.

After the birth of their daughter in Liverpool, Timothy and Harriet moved to her home territory of Southwark and their next three children were baptised at St Mary Magdalen, Bermondsey. Their address was Upper George Street, Southwark and Timothy’s occupation was given as ?gentleman’. All told, 10 children were born to Timothy and Harriet of whom at least eight survived to adulthood. The varying fortunes of these children provide an instructive story of the ups and downs of Victorian life. With life insurance in its infancy and no welfare state, much depended on the continued prosperity of fathers and husbands: fortune favoured the confident, lucky or crafty: the fate of women depended on their menfolk. This was an interesting group of adults and I have incorporated an account of what we know of their lives as a separate postscript to Vivien’s story. Their lives illustrate what Geoffrey Best in his book Mid-Victorian Britain, published by Fontana in 1979, says:

“Investment in government securities, railways and real estate was no doubt how most men made provision for the worst; nothing then seemed as safe as houses. But how much could they save? It was repeatedly stated to the Commons Select Committee on Income Tax in 1861 that only the most fortunate and best-established professional men ever made enough to be able to insure their lives for a worthwhile amount. In times when sons cost more and more to educate and daughters still had no respectable prospects but matrimony, a professional father’s death could suddenly topple his family to equality with an artisan’s.”

But Frederick Charles Triebner, son of Timothy Frederick, does not seem to have been Harriet’s son. According to his marriage and death certificates he was born around 1846 and therefore Harriet, born in 1803, could have been his mother. Her last known child, Gertrude Margaret, was born in Hornton Street, Kensington in 1845. However, Frederick was not listed with the family in the 1851 census and when Timothy submitted his expenses to the bankruptcy court in 1848 he claimed for nine children, thus not including Frederick. He declared Timothy Frederick as his father on his marriage certificate and, given that Timothy must have been known to Fanny Russell’s parents as the husband of their other daughter, Rosa, it seems safe to assume that Timothy had recognised Frederick as his son. (Presumably Frederick was registered, if at all, under his mother’s name.) Timothy recognised two others of his illegitimate children, who were not registered as Triebners in the civil register of births, in the will he signed three days before his death in May 1875. These were Arthur John Triebner and Enid Theresa Triebner, named as his youngest son and daughter and the only beneficiaries of his estate. In the 1871 Bristol census, Arthur was listed as living with his father and Rosa at Loretta House, Ashgrove, Redland. He was said to be 13 years old and his birthplace was Lancashire: Enid who would have been around 11 years old, was not living with her father and Rosa for this census. Arthur and Enid, born around 1858 and 1860, were obviously not Harriet’s children but the evidence suggests that they were full siblings. Rosa died in 1874 and it was Arthur who witnessed and reported his father’s death. Timothy’s will left his business interests as a commission agent to Arthur and he also set up a trust with Arthur, still a legal minor, and William Meek, a retired customs collector, as signatories, to provide for the education and maintenance of Enid. She was to receive the principal when she reached 21 years: his estate was proved at less than £600 so there was probably not a large fortune for her. After Timothy died Arthur and Enid seem to have moved to London together. In 1876 Arthur married Mary Ann Hurst, the daughter of Matthew Hurst, a fireman on the Great Eastern Railway. The Hursts lived at 16 Prebend Street, St Pancras and censuses show that they took a number of lodgers. In 1879 Enid, aged 19, married Robert Freeman, a coachman. Both Enid and Robert gave 16 Prebend Street as their address and the Hurst parents were the witnesses at their wedding. They were presumably lodging with the Hursts, Arthur’s parents-in-law. In the 1881 census Enid and her husband the coachman were still living in Pancras. Enid was calling herself Emily and she gave her birthplace as Manchester. We know from a trade directory that Timothy was working in Liverpool in 1858 so the birth of these two youngest children in Lancashire is not surprising. Rosa was the right sort of age to be their mother and the fact that Arthur at least was living with her and Timothy in 1871 might support this. However, if Timothy and Rosa had children together before Harriet’s 1861 death, it seems strange that they did not marry until 1866. Also, court papers in the Bristol Archives, dealing with the many claims on Timothy’s estate, show that Arthur told William Meek, the trustee of his father’s will, that he and Enid were illegitimate and not the children of Rosa known by Meek as Timothy’s wife. There is one more mysterious Triebner in the civil registers who was not registered at birth as a Triebner. Marion Zillah Triebner, a spinster, died aged 73 in 1922. She was therefore born around 1849 when Harriet was about 46, but she was not listed with the family in the 1851 census. Timothy Frederick was the only male Triebner old enough to be fathering children in 1849. Perhaps Marion Zillah and Frederick Charles, both born in the 1840s, had the same mother and perhaps the Marion Agatha and Agatha Marian who were Frederick’s daughter and granddaughter were named after their aunt Marion Zillah. In 1888, Arthur who had declared himself illegitimate to William Meek, named his baby daughter Agatha Marian. It would be good to know whether this was a usual combination of names or whether it has a family significance. According to her death certificate, Marion was an art mistress and she died in a convent in Brighton established by an order of French nuns. They ran a school, on the same site, presumably the one where she had taught. Curiously enough, the Bristol papers show that Enid was in a convent in Holland when William Meek had to contact her on Timothy’s death. Perhaps convent life was Timothy’s solution for illegitimate daughters.

From the safe distance of a century and a half, Timothy Frederick Triebner is an interestingly racy person to find in a family tree. Not only was he somewhat buccaneering in his family life, but he also seems to have had a similar approach to business. As already mentioned, he and Harriet started their married life in Liverpool where the younger Harriet was born, and then came south to London. From Upper George Street, Southwark they moved to Union Court in the City, where Susan Maria was born in 1837, and then to Hackney. It seems that the whole Triebner family had moved to London from Leeds. Timothy Traugott Triebner, Timothy Frederick’s Georgian-born father, died at 5 Queen’s Road, Hackney in 1842. He was 64 years old and his occupation was ‘gentleman’. Timothy Frederick Triebner witnessed and reported his death. Timothy Traugott’s widow, the former Betty Rhodes, and her two daughters, Elizabeth and Maria Ann, stayed on in Queens Road until Elizabeth married James Abraham Rhodes in July 1848. James, a gentleman, came from Cheshire and was presumably a relative of Betty Rhodes. The three women then moved north with James. In 1860 Maria Ann was listed in the Liverpool trade directory as the owner of a boarding school in St Paul’s Road, Tranmere. Betty died in Birkenhead in 1864.

When the two Triebner families were living in Hackney, Timothy Frederick’s fortunes were rising steadily. At that time Hackney was in the early stage of its transformation from quiet, rural village surrounded by market gardens and watercress beds to the industrial centre it became by the later years of the nineteenth century.

Their home in Mare Street would have provided a pleasant setting for the Triebners and their growing family. The 1841 census shows them living there with six daughters: Harriet, Frederica, Jane, Susan, Beatrix and Mary. Timothy’s occupation was Russia Broker. Their sons, Frank Tatton and Harry Nicholas, were born in Hackney in 1842 and 1843. By 1845 when Harriet’s last child, Gertrude Margaret, was born in Kensington Timothy was at the height of his mercantile career.

Their home in Mare Street would have provided a pleasant setting for the Triebners and their growing family. The 1841 census shows them living there with six daughters: Harriet, Frederica, Jane, Susan, Beatrix and Mary. Timothy’s occupation was Russia Broker. Their sons, Frank Tatton and Harry Nicholas, were born in Hackney in 1842 and 1843. By 1845 when Harriet’s last child, Gertrude Margaret, was born in Kensington Timothy was at the height of his mercantile career.

From 1834 until 1848 Timothy Triebner appeared in trade directories as a merchant, or Russia broker, at 81 Old Broad Street and at the Baltic Coffee House, Threadneedle Street. The Baltic Coffee House was an exclusive club of traders, as described by Stephen Inwood in his 1998 History of London. In 1823 “the Baltic merchants set a limit of 300 members on the coffee house’s subscribers’ room, creating a members’ market in which information would take the place of speculation.” “The merchants who met in the Baltic Coffee House traded in tallow, oil, hemp, grain and other Russian and north European imports.”

Timothy Frederick Triebner Esq. was listed in the Court Directory of 1845 and 1846 as living at 10 Hornton Street, Kensington. Residence in Hornton Street, which still exists, running off Kensington High Street, then as now, indicates some considerable prosperity. In the 1847 and 1848 directories Timothy was still listed as a Russia broker at 81 Old Broad Street, but the family had disappeared from Hornton Street and the 1849 directory has no entry for Timothy Triebner. Instead he had appeared in the London Gazette of 3 December 1847. He had declared himself bankrupt on 27 November and, in the Gazette, Timothy Frederick Triebner, Russia Broker, Dealer and Chapman, was required to surrender himself to the Court of Bankruptcy. The bankruptcy proceedings took place in January 1848 and a summary of the transcript is held at the National Archives in Kew. It emerged that Timothy and Edward, Harriet’s brother, had been jointly speculating in railway shares. One of Timothy’s debts was £48 for his half of the investment: he had issued a bank draft to pay for them which had not been honoured. Apparently Timothy’s problems had started with the dissolution of his partnership with Conquest in May 1845 and it seems that they had gone to law about the settlement. Timothy owed about £900 to Conquest and about £300 to tradesmen. In addition he owed money to members of the Rhodes family, including J A Rhodes, presumably the husband of his sister Elizabeth. According to Timothy, his friends and family would never have demanded payment “until his business had been such as would have enabled him to gradually liquidate them.” It was his business creditors who had forced him into bankruptcy. There was a telling comment, however, from the official who had checked Timothy’s accounts which suggests that it was unlikely that Timothy would ever have rescued his business at this time. It was said that the first bankruptcy sheet filed in this case was so informal that another had been substituted, also found inaccurate but amended in red ink. Also there was no cash book and the bankrupt never kept receipts for anything (!).

Timothy had to submit a record of his annual expenses, which came to an agreed sum of £1,835. This suggests that Timothy was spending, if not earning, at just below the highest income level in the country in 1848. One of the expenses which Timothy included was £12 for taxes as well as £50 for the rent of Horton Street. Others of his expenses were the costs of maintaining a wife and nine children, thus not including Vivien’s great-grandfather, Frederick Charles. Timothy claimed to spend £87 on clothes for Harriet and the nine children and £45 on his own tailor, hatter and shoemaker, which perhaps suggests something about his priorities. Pew rent at the local church where the large Triebner family presumably joined other rich Kensington families in Sunday worship, was eight guineas a year and Timothy subscribed twelve guineas a year to the Baltic Coffee House. A doctor and nurse attending the birth of Gertrude Margaret were paid nine and six guineas respectively. Meanwhile, Timothy paid his clerk £40 a year and his office boy five shillings a week.

Another of Timothy’s stated expenses was £31.10s. for pianoforte hire, possibly related to his daughter’s studies at the Royal Academy of Music. The Academy’s ledgers show that Harriet was auditioned and admitted for voice study in October 1847, just a month before Timothy was declared bankrupt. After various communications from each of the Triebners, relating to what the Academy Committee minutes described as “the peculiar circumstances”, Harriet finally left the Academy and, aged 19, in November 1849 at St Pauls Hammersmith, she married 37-year-old Richard Wilson a Clerk in Holy Orders from St John’s Church, Leeds. Richard’s father was a surgeon and Timothy, two years after his bankruptcy, was described as “Gentleman” on the marriage certificate. There was a large turn-out of Triebners to witness this wedding: Harriet, Timothy, Timothy’s sister, Maria Ann, and two of the older children, Frederica Georgiana and Jane Betty, all signed the register. It is probably a coincidence, but the 1850 Post Office directory shows Wilson and Lancaster as Russia brokers at Timothy’s old business address, 81 Old Broad Street. Perhaps Harriet’s marriage was bound up with a business arrangement between the Triebner and Wilson families. Be that as it may, Harriet’s marriage is also an example of the Triebners’ continued links with northern England. The Triebner diaspora eventually spread through London and the Home Counties, Cornwall and Somerset: but Betty Rhodes’s relations were still based in Yorkshire, Cheshire and Lancashire. Harriet moved to Leeds after her marriage, just as her aunt Elizabeth had gone to Cheshire with James Rhodes the previous year.

With one less mouth to feed, Timothy and Harriet are next found in the 1851 census living at Heathfield Cottage, Wood Lane, Shepherds Bush. This was apparently a very isolated dwelling in a not very salubrious area. The eight children were all “scholars at home” and Timothy was a commercial traveller. Despite their presumably reduced circumstances they still had the help of two resident servants.

My next sighting of Timothy is in the 1858 Liverpool Post Office directory. He was listed as a commission agent at 11 Temple Court, North John Street, Liverpool. His youngest son, Arthur was born in Lancashire around this time and Enid was born in Manchester around 1860. But by 1859 Timothy had reappeared in the London directory, living at 10 Addison Terrace, Notting Hill. It was from there that his daughter, Beatrice, married John Wilcox, an assistant surveyor, in September 1860, with Timothy, a merchant as a witness. Her mother, Harriet, was still alive but she died of chronic kidney disease at 9 Stratheden Villas, Goldhawk Road in February 1861. She was 57 years old and her death was witnessed and reported by her son, Frank, of the same address. Unfortunately in April when the census was taken this house was unoccupied. Triebner and Lee, Provision Brokers, were listed in the 1862 London directory at 249 Tooley Street., Southwark. However, by New Year’s Day 1866 when Timothy married Rosa Russell at a Register Office in Westminster he was living in Cambridge Street, Pimlico. Unfortunately much of the 1861 Pimlico census was inadvertently destroyed at the time so there is no record of what family responsibilities Timothy assumed after Harriet’s death, or for which members of his numerous families.

There are no London records of Timothy after his 1866 marriage but he was recorded in the 1871 Bristol census as a general merchant, and listed in the 1872 Bristol directory at Loretta House, Ashgrove Road. There was one more move before Rosa died in 1874: like Timothy a year later, she died at 27 Meridien Place, Clifton. According to his death certificate Timothy had had an abdominal obstruction for 21 days before the three days of exhaustion which ended in death. One of the witnesses to the will he made just before that last three days was a Gertrude Annie Rhodes of Rock Ferry, Cheshire. She was the 25-year-old daughter of Timothy’s sister, Elizabeth Rhodes, presumably arrived to help in nursing the invalid. It seems that there were no hard feelings about Timothy’s borrowings from the Rhodes family in the 1840s. In the will, Timothy was described as a commission agent, and it was this business that he left to Arthur John. However when Enid married in 1879 she gave Timothy’s occupation as wine merchant and this suggests that Timothy had business contacts with his two surviving sons by Harriet. Frank, the son who was with his mother when she died, was manager of a brandy house in Newington Causeway when he married in 1873 and their other son, Harry, committed suicide in 1879 after he had been discovered embezzling money from the accounts of the wine merchants he managed in Truro. This “melancholy event” was reported at length in the local newspaper, the Royal Cornwall Gazette.

Timothy’s third son, Frederick Charles, was not involved in any of these business activities. He had somehow become a midshipman, as recorded on his marriage certificate, but wherever he had spent his childhood and early youth, he must have had contact with his father in the 1860s. As already mentioned, Timothy and Frederick both married in 1866 and their wives were sisters. Moreover, Rosa married Timothy from the same address, 11 Bartholomew Road, as Frederick and Fanny gave when they married six months later. However, this is the only known link, bizarrely strong, between Frederick Charles and his father.

Frederick Charles’s origins remain mysterious. The birth and parentage of his son, the younger Frederick Charles, are well documented, but this Frederick Charles seemed uncertain about them when he gave his birthplace as Peckham on the 1891 census. At age 21, Vivienne’s father described himself as a furrier on her 1887 birth certificate. Like Harry Barder‘s father and brothers when they were establishing themselves as furriers, he seems to have made a number of abortive starts, and in 1891 and again in 1902 his occupation reverted to commercial traveller. By 1903, however, Frederick Smith (the name he used for the rest of his business career) is listed in the London directory as a furrier at 29 Spelman Street, Spitalfields. These premises survived the war and this was still his business address in 1946. He and Eliza Annie Quartly separated some time in the 1890s and Frederick Charles and his second wife had four more children.

The 1901 census shows Eliza Annie, his abandoned wife, living in East Ham with the three Triebner daughters. Violet, the oldest, aged 14, was already working as a book binder sewing apprentice. In 1908, his two younger daughters were married. Agatha Marion married Tyrrell Walter Moody at Christ Church, Mayfair, in the October and in November 1908,Vivienne married George Young. Violet Nelsie, the third sister, married Montague Record, a widowed Master Lighterman in 1913.

When Vivien married Harry Barder, the furrier, in 1933, she must have known that her grandfather was still alive and working as a furrier. One of Annie’s married sisters was a witness at the wedding of Nelsie Vivien Record, aka “Aunt Peggy”, in 1933 at St John’s Wood, so the Quartly family connection still existed. Brian was 16 when his Triebner great-grandfather died but knew nothing about his life or death. He has no memories of the great-grandmother who lived in Bristol until she died when he was 6. The sad circumstances of his grandmother’s death were kept from him, even when he was an adult: no doubt for understandable, kindly reasons.

Careful English record-keeping and the extraordinary accessibility of records have enabled us to build up a reasonably detailed picture of the many families who are part of Vivien’s background. They form an amazing mosaic of widely different occupational and regional backgrounds: the Dorset-born Rose and Crown publican; the journey of Simon Andrews, the telegraph engineer and his wife, Emma Woods, who came from their agricultural childhood to the crowded, railway-dominated streets of Kentish Town; the engraver on wood who married Cecilia, daughter of Joseph Ryan, the Irish plumber; John Russell the Bath schoolmaster and his wife whose Catholicism had impressed itself on the family memory even if no other memory of them survived; and, above all the Triebners, migrants to and from Yorkshire, and their eventful lives.

Brian Barder, Vivien’s son, now knows a lot about his mother’s “blood family”, but his only relationship is with her ‘step-family’: he has a fond friendship with Triska Blumenfeld, Ivan Anderson’s artist daughter who lives happily in New Zealand. After so many years of ignorance about Viv’s family it turns out to be peopled by characters worthy of an unlikely novel.

Dear Jane,

My name is Geraldine Walsh. I live in Mosman, a suburb of Sydney. I have been researching a series of WW1 portaits of young soldiers found in the basment of our local library. One is of “Gnr I Anderson”. There is a possibility that it is a photo of Ivan Francis Anderson who was born in Christchurch, NZ. Was Francis the middle name of the Ivan Anderson in your husband’s family history? Do you, by any chance, have a photo of your Ivan whne he was younger?

Sincerely,

Geraldine Walsh

Brian writes: This is certainly the same Ivan Francis Anderson (mentioned and pictured in the web piece above). Jane has replied privately to Geraldine, to whom our thanks for taking the trouble to write.

What a story! I am interested in further details of William Meek, Trustee to the fathers will (Timothy) if you have them.

Regards

Gloria

Hello – I have my family tree on ancestry, today I was tracking the history of Rosetta Sarah Andrews my 4th cousin 3x removed. I found the record of her second marriage to Frederick Ernest Spraggons and her death which followed so closely after. Isn’t it strange how the hairs on back of your neck prickle and you start to wonder what happened? Out of shear curiosity I ‘googled’ Frederick and your page came up! What a story – and how satisfying it is that my instincts were correct! Would you please allow me to use Rosetta’s photo? And may I put a link to your page on my tree? Tragedy seems to run in this family. I am related to Rosetta via her mother’s line the Woods family. Without boring you with all the data, briefly, Mary Ann Woods b 1817 m Stephen Knott, their eldest daughter Deborah m Alfred Liles. Their daughter Ethel Jessie m William Eustace Graydon and their daughter Edith was hanged . The Thompson/Bywaters case. Ethel Jessie was my mothers Aunt.

Thank you for such an interesting article, my regards Margaret

Brian writes: Thank you for this, Margaret. We do indeed seem to have sprung from interesting families! By all means use Rosetta’s photograph in any way you like, and put a link to my wife Jane’s article about my mother, Viv, on your family tree. It’s all in the public domain.

Hi I was excited to find your webpage and get more information on the Triebner family. I am related to the Kroer family of Ebenezer GA (formerly Salzburg Austria) that Christoph Friedrich Triebner married into in 1769.

I have included the link to my page for him on the United States version of Ancestry.com. I am from Georgia in the USA and have researched the family from our side of the pond. If you would like any more info on his time in Georgia, just contact me and I can send some of the research I have found about his time as pastor here and of course his wife’s family. He was involved in quite the scandals here. Could you please let me know how you would properly list the location of his new home and sons’ homes in England? Is it city, County, District? If so which ones are correct? Do you know his 3rd child’s name? You only list 2. I have record of a 3rd son who died a few days after birth in 1770 from the Jerusalem Church Records in Ebenezer, GA. Since the British overtook the town of Ebenezer, some records were lost and the other children’s births may have been lost.

Thanks for your time and information.

Rhonwyn (yes I have a Welsh name)

Brian writes: Thank you for this. Please see my response to your comment at https://barder.com/family/history/triebners/comment-page-1#comment-162161.

Here is the link in the comment body in case anyone else wants to see it. It is the USA website please note, not UK.

http://trees.ancestry.com/tree/29715727/person/12781966827

Wrong Name Given by me

Sorry I meant to say Christophe Friedrich Triebner married Frederica Maria Gronau who was the daughter of Catharina Kroer. I accidentally listed her mother’s last name.as his wife. I am related to the Kroer side.

Brian writes: Thank you for this. Please see my response to your comment at https://barder.com/family/history/triebners/comment-page-1#comment-162161.