Can you keep a secret? Parliament vs. the Executive

In Ephems last week I wrote this about the publication of evidence, hitherto classified (presumably 'secret' or 'confidential'), given to the Butler Inquiry in June 2004 by Carne Ross, the British former diplomat who subsequently resigned from the Diplomatic Service over Iraq:

Last month (on 8 November 2006) a member of the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Select Committee made strenuous efforts to persuade Carne Ross to pass to the Select Committee his classified evidence to the Butler Inquiry under the protection of parliamentary privilege (the transcript of his exchanges with Ross and with the Chair is well worth reading), but the Committee seems subsequently to have decided not to ask for it.

Today, however, the Independent newspaper has published the full transcript of Carne Ross's hitherto secret evidence to the Butler Inquiry.

An aside in yesterday's Observer, and further research, have alerted me to some significant errors in what I wrote. First, it seems from a closer scrutiny of the Butler Inquiry (into intelligence on WMD in the lead-up to the Iraq war) that Butler's eventual published report did not reproduce any of the written (or indeed the oral) evidence submitted to it, so the fact that Carne Ross's written evidence was not published had no special significance. (Of possibly greater interest, though, is the fact that Carne Ross's name doesn't appear in the Butler report's list of witnesses: presumably he is one of "two further witnesses who asked for their identities to be protected".) More important, however, is the fact that the Independent newspaper was not the first to publish Ross's previously classified Butler evidence, as I had thought: it was in fact first published on the website of the House of Commons Select Committee on Foreign Affairs. This raises some interesting further issues.

I have not yet been able to discover how Ross's evidence to Butler came to be classified. When he submitted it, Carne Ross was still a member of the Diplomatic Service, then as now bound by the Official Secrets Act but also by the ordinary code of conduct and discipline applicable to all public servants. The Cabinet Secretary granted immunity from disciplinary procedures to any public servant on account of anything said in evidence to Butler, but this would hardly have given Ross carte blanche to make public information which was itself classified. At any rate, his evidence to Butler certainly was classified, and Ross was clear in his oral evidence to the Foreign Affairs Select Committee that he would be in legal trouble if he simply published it on his own account.

This prompted one member of the Committee in particular to press Ross to hand over the text of his Butler evidence to the Committee under the protection of Parliamentary privilege, although the Committee Chair urged Ross to take further legal advice before doing so. Ross himself made it clear that he was keen to get his Butler evidence into the public domain and saw a request for it from the Committee as a good way of doing so. There was however apparently some disagreement within the Committee about the propriety of inviting Ross to hand over this classified information. From the Committee's website:

Motion made and Question proposed, That the Committee do not send for Mr Carne Ross’s evidence to Lord Butler’s Review of Intelligence on Weapons of Mass Destruction.—(Mr Greg Pope.)

Mr Pope's Motion must have been defeated, because on 6 December the Clerk to the Committee wrote to Carne Ross in terms that made it quite clear that he was expected to hand over the document:

At its meeting today, the Committee resolved to send for your unpublished written evidence to Lord Butler's review of intelligence on weapons of mass destruction.

I would be grateful if you would make arrangements to hand over the evidence at your earliest convenience.

Ross replied on the same day in terms that suggest that he had taken further legal advice about how to cover himself against any accusation of personally publishing classified information, by sheltering behind parliamentary privilege:

Please find enclosed a copy of my evidence to the Butler inquiry in 2004, which is disclosed to the Foreign Affairs Committee on the basis of and in accordance with its express requirement that I disclose it as part of my evidence to the committee.

It is of course a matter for the committee what if anything it wishes to do with the evidence but it would, in my view, be unfortunate if the committee were publicly to rely on or comment in any way on my evidence without making the document itself public. It would be strange and unfair if comments were to be made about this document out of context and without the public being aware of its contents or my being able to make any comment on it.

I want to make clear to the committee that I do not regard this evidence as anything other than a small part of the story of policymaking before the war. I was but one of several officials involved, and of course I was not at the most senior level. I also left the British government—on sabbatical—in June 2002.

These events prompt a number of questions. If a minister of the Crown, or his officials acting in the minister's name, judge certain sensitive information to require classification on grounds that its publication would be damaging to the public interest, can a committee of MPs demand that a witness giving evidence to them should nevertheless hand it over to them? Having received it, is the committee itself not bound by the Official Secrets Act not to disclose it to anyone else without the agreement of the relevant minister: or may it safely do so on the grounds that it is covered by parliamentary privilege and immunity? Did this particular committee consult the Foreign & Commonwealth Office before publishing the Ross Butler evidence by putting it on its website?

There are other pertinent questions of a slightly different kind. Now that we can read Ross's evidence to Butler, either on the Select Committee's website or in the Independent newspaper, does it seem that its publication will in fact have damaged the public interest, or will it have damaged only the credibility of the government in the controversy over the legality or otherwise of the attack on and occupation of Iraq — not quite the same thing? Is a government entitled, legally or morally, to try to protect itself and its reputation by withholding certain potentially damaging information from publication by classifying it, even if publication would not pose any threat to the wider public interest — such as the public interest in having available all information that helps us to judge the credibility and integrity of our government? On the other hand, is it possible for officials and others to give genuinely frank and uninhibited advice to ministers, including advice that might be unwelcome to ministers because it warns of the likely malign consequences or even illegality of a course of action that they plan to take, if any old official who sees it is entitled to publish it, if necessary under cover of parliamentary privilege (or on a foreign website)? Wouldn't such a régime result in all sensitive or unwelcome advice from officials either being suppressed and withheld from ministers, or else transmitted orally, with no record of it kept, and any written evidence of it quietly destroyed? The consequences of any such development would be disastrous for uninhibited private debate on policy within government and for later accountability to parliament, public opinion and historians. Certainly no other government in a comparable democracy gives to its officials and advisers anything like such licence to publish and not be damned: the development of public policy is nowhere conducted in a goldfish bowl.

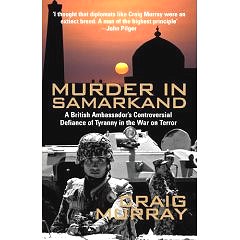

Very similar issues arose earlier this year over the efforts of the Foreign & Commonwealth Office to prevent Craig Murray, controversial former ambassador to Uzbekistan, from publishing, first on the Web and later in his book, the texts of classified documents related to his long dispute with the Office, leading eventually to his own resignation from the Service. Once these texts were published on the Web, and it became known that the FCO was trying to get them removed from it, so many websites in Britain and abroad made copies of them and re-published them as 'mirror sites' that the FCO's efforts failed, and indeed they are still available on the Web to any ordinarily diligent searcher. The FCO did however succeed in getting the texts expunged from Craig Murray's book, by threatening his publisher with legal action if they were published there. I commented on these issues at length (!), and also exchanged (courteous) arguments about them with Craig Murray, in earlier Ephems posts here, here, here and here.

Very similar issues arose earlier this year over the efforts of the Foreign & Commonwealth Office to prevent Craig Murray, controversial former ambassador to Uzbekistan, from publishing, first on the Web and later in his book, the texts of classified documents related to his long dispute with the Office, leading eventually to his own resignation from the Service. Once these texts were published on the Web, and it became known that the FCO was trying to get them removed from it, so many websites in Britain and abroad made copies of them and re-published them as 'mirror sites' that the FCO's efforts failed, and indeed they are still available on the Web to any ordinarily diligent searcher. The FCO did however succeed in getting the texts expunged from Craig Murray's book, by threatening his publisher with legal action if they were published there. I commented on these issues at length (!), and also exchanged (courteous) arguments about them with Craig Murray, in earlier Ephems posts here, here, here and here.

I remain convinced, on the basis of personal experience as much as of any academic assessment of the arguments, that a condition of good government in a democracy is the right and ability of governments to protect some of the sensitive information in its possession from publication, at least until publication no longer threatens to damage the wider public and national interest. The present government's recent encounters with Craig Murray and now with Carne Ross suggest that in some circumstances government may find it impossible in practice to exercise that right. If so, even the most sensitive information (affecting, for example, national security and relations with foreign governments) must now be vulnerable. The problem, I believe, lies not only in the advance of information technology but also in the power of government to decide unilaterally what may and what may not be published. The machinery in the Freedom of Information Act enabling an independent referee to arbitrate between an applicant for the release of specific information and a government department that refuses to provide it, may need to be broadened so that all disputes over the publication of classified information can be resolved by a disinterested authority, and not by threats, litigation, or the exercise of raw power or cunning evasion, as at present.

Update (19 December 06): The first comment, below, by Craig Murray is well worth reading.

Brian

Good post. Just a couple of points to provoke further thought.

In my case, I was clearly open to the possibility of prosecution under the Official Secrets Act at several stages in the process. I was confident the government wouldn't do this. Not that they are terribly kind-hearted, rather they would appreciate that no jury would be likely to send me to prison for campaigning against torture.

Which leads me to my main point. I think you are right about a certain amount of confidentiality being required in government, though we might argue how much. But I think this governmnet, in pursuit of the so-called War onTerror and the invasion of Iraq, used that confidence to practice deceit on parliament and the wider public, to reduce civil liberties and to start an illegal war of aggression. In these circumstances, some who had always worked within the rules of the system, such as Carne and I, will feel compelled to step outside.

Incidentally Carne did better than me in managing to appear before the Foreign Affairs Committee, which refused to call me as a witness or to publish my written statement. This despite the fact that they questioned seven other witnesses about me and my reliability. I did however manage to give evidence to the European Parliament, and feature in their draft report on extraordinary rendition.

One last irony. In the first Gulf War I was a young First Secretary heading the FCO section of the Embargo Surveillance Centre, with a worldwide remit to detect and thwart Iraqi attempts at weapons procurement. We reported straight to the PM, and were much praised. My ablest assistant was Carne Ross.

I agree with most of the above. I believe this issue is now pretty well out of control, perhaps to use the cliche a disaster waiting to happen. I do beg anyone commenting further not to resort to the well worn accusation that officials and the government have a "cult of secrecy". Secrecy has its place, both in government and in any other institution, though it is perfectly true that too many documents used to be over-classified in the FCO when you and I, Brian, were young.

A couple of anecdotes, if you permit, to illustrate my point. First, in the British High Commission in Cyprus in the 1970s we were instructed by the FCO to draft some what-if papers, as they might now be called, about various things which might go wrong in that problem island. As usual we worked closely with American colleagues, one of whom said to me how much he wished that the State Department could work up some similar papers. I asked why they didn’t, and he said that that problem was that any such papers would be in the American newspapers within a couple of weeks, which would have done more harm than good.

Second, when I retired I was libelled in a national newspaper. I asked for and eventually obtained a published apology (little good it did me). My lawyer suggested that I might get the newspaper’s lawyers to pay part of his fees. We successfully made such a demand, but the newspaper’s lawyers made it a condition that their agreement to pay would remain confidential. I will therefore refrain from naming the newspaper, but I will give you a couple of clues: begins with G and ends with N..