Aurora : Mediterranean, Bosporus and the Black Sea

30 August to 17 September, 2003

Day 1 Saturday 30 August: Departing from Southampton

First impressions excellent. An enormous ship, a half-marathon’s distance from stem to stern (or so it seemed when we tried it out) and about half a mile high measured from the water-line. Our cabin is roomy, with a queen-sized bed, loads of wardrobe and cupboard space, a desk big enough for laptop, full sized keyboard and mouse, and—ultimate luxury—wall-to-wall sliding French windows onto our private balcony with its two reclining chairs and folding table. From here we looked down at the brass band on the quay, far below, as they played traditional farewell tunes while the giant ship slipped silently away into the Solent , bang on time. The sun shone warmly onto our balcony from an almost cloudless sky and workmen waved to us from the jetties and quays as we glided past.

It’s been pretty eventful ever since we came aboard. Our five sizeable suitcases, last seen being loaded onto a trolley and wheeled away from the car moments after we arrived at the P&O Mayflower terminal, appeared in our cabin with plenty of time for us to unpack them and push the empty cases under the bed. We sampled the appallingly tempting afternoon tea in the Orangery and ate too many tasty sandwiches, sausage rolls and cakes. We obeyed the summons to our Muster Station (one of the big theatres) for Boat Drill, and listened respectfully to the voice of  the Captain over the loudspeakers sternly admonishing us not to abandon ship or leap into the water except as a last resort, and even then only when directed to do so by a member of the crew. Fragrant, uniformed young women crew members lining the stage and the sides of the theatre demonstrated the art of donning a life jacket, as disciplined in their movements and glassy smiles as if performing synchronised swimming. As a final treat we were allowed to try putting on our own life jackets. This accomplished, we were dismissed, and filed thoughtfully out. Time for a bath or shower, change into “Smart Casual” (the costume decreed for this first evening), and another wander round before dinner at 8.30 and the revelation of who are to be our table companions for the next 17 nights.

the Captain over the loudspeakers sternly admonishing us not to abandon ship or leap into the water except as a last resort, and even then only when directed to do so by a member of the crew. Fragrant, uniformed young women crew members lining the stage and the sides of the theatre demonstrated the art of donning a life jacket, as disciplined in their movements and glassy smiles as if performing synchronised swimming. As a final treat we were allowed to try putting on our own life jackets. This accomplished, we were dismissed, and filed thoughtfully out. Time for a bath or shower, change into “Smart Casual” (the costume decreed for this first evening), and another wander round before dinner at 8.30 and the revelation of who are to be our table companions for the next 17 nights.

It’s lucky that we shall have a “day at sea” tomorrow, crossing the dreaded Bay of Biscay, with time to explore the three swimming pools, the five or six cafés and restaurants and twelve bars, the two theatres, the cyber room with banks of computers for internet access (at a price), palm courts, ballrooms, casinos, gym, beauty salons, medical centre, and all the rest of the luxurious facilities. But now it’s dinner time.

Day 4 Tuesday 2 September: Between Lisbon and Athens

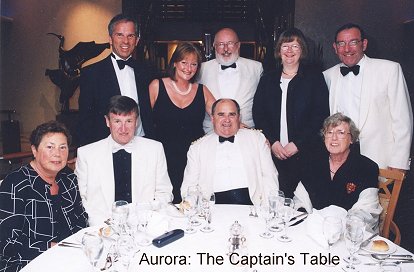

One of the great risks in cruising is that one’s randomly allocated dinner-table companions, with whom two or three hours will be spent every one of the (in our case) 18 evenings on board, may turn out to be a huge taciturn north countryman with a small harassed wife and no conversation, or an affably talkative middle-aged Daily-Mail-reader endlessly inviting agreement with her views on Iraq, the physical punishment of small children and the kind of prison conditions required to deter re-offending. What a relief, therefore, to find on the first evening that we are to share our table with three very agreeable Scottish couples, all articulate and funny: a retired senior police officer now in charge of security for a big local authority, a former member of the RAF, now in CCTV work, an anaesthetist, a nursing Sister, and a Services charity welfare officer. Two of the men appeared for the first formal black tie evening (the first of six!) resplendent in full Highland evening dress, daggers in socks and silver sporrans adorning the kilt—‘kilt’ being, we all know, the plural of ‘kilt’, like ‘sheep’. There are clearly many agreeable conversations and a good deal of merriment ahead.

One puzzle was quickly solved. Although only the four couples—six Scots and us—appeared at the table that first evening after we had sailed from Southampton , our table was laid for nine. A friendly Goanese waiter explained that the single extra place, unoccupied that night, was reserved for the Captain. We speculated at length, and fruitlessly, about how and why we had been chosen to sit at ‘The Captain’s Table’, even though the Captain wasn’t sitting at it: not, at any rate, in the flesh, although we supposed that he might have been with us in spirit. The mystery was deepened by the fact that the former police officer, on an earlier Aurora cruise a couple of years previously, had been allocated to the identical table, although not (fortunately, from what he told us) to the same Captain. On the second, formal, evening, when dinner had been preceded by the traditional Captain’s ‘Welcome Aboard’ black tie reception, the Captain at last appeared corporeally at our table, and proved to be an excellent dining companion. An Australian by origin, from near Adelaide in South Australia, he regaled us with many good reminiscences of unruly families and individuals whom, over the years, he had found it necessary to expel from his ships, mostly for persistent drunkenness or for behaviour disturbing to other passengers or crew. Sentence of expulsion had mostly been pronounced while the ship was on one of her port visits, the offenders assisted by P&O to make their return travel arrangements back to the UK, but (naturally) at their own expense. One exceptionally drunken group had for the first time exceed the limits of tolerability only after the ship had left her last port of call and was heading for home. “There’s nothing you can do to us now,” the drunks crowed at the Captain. “On the contrary,” said the Captain, putting them in the ship’s launch and despatching them to the nearest fishing village on the adjacent coast to find their own way home. Shades of Captain Bligh! Game, set and match to the South Australian.

That night of the Welcome Aboard black tie reception turned out to be the Captain’s birthday, suitably celebrated by the dining-room staff and the ship’s officers by the presentation of balloons, a large cake and a spirited rendering of ‘Happy Birthday to You’. Our pretty young Filipino wine waitress spent the evening whispering suggestions in the Captain’s ear about wines appropriate to the occasion, eventually costing him three bottles of an excellent Sancerre and two bottles of Mumms bubbly for the nine of us. The following evening (“informal – jacket and tie for the gentlemen, cocktail or day dress for the ladies”) the table was laid for eight and we haven’t seen the Captain since.

Ashore in Lisbon on Day Three we took the excursion out of the city by coach and over the mountain to the south, navigating the narrow highway along the edge of the escarpment with stunning views of the Atlantic and sunlit beaches far below us until we descended steeply into the pretty old fishing village, now a busy container port, of Setubal. Passing the Technicolor boats of the fishing fleet, close to ruin by ruthless competition from Spanish fishermen, the coach dropped us for half an hour in the busy shopping centre of the Old Town where J and I found a modern supermarket for large bottles of fizzy mineral water, concentrated fruit cordial and a few cans of beer for the fridge in our cabin, thus defeating the fanciful prices charged by Aurora’s bars. Don’t on any account tell P&O or we’ll be blacklisted for ever after. Some fellow-passengers told us at lunch yesterday (free seating at lunchtime so it’s pot luck who your sitting with) about one cruise liner which confiscated all duty-free drink bought by passengers while ashore on port visits, returning it to them only when they disembarked at the end of the cruise, thus preserving the ship’s monopoly of alcohol sales at monopolistic prices. Actually, apart from soft drinks and mineral water, drink prices aboard Aurora are not at all unreasonable.

The water temperature in the ship’s principal pool is kept at a steady 29 or 30 degrees, too cool for the Americans but perfect for the Brits. In fact, we haven’t yet discovered any Americans among the passengers. According to one of the Scots, this is because Americans have stopped flying since 9/11 and the great East Coast power blackout, so they have all cancelled their bookings for cruises starting and finishing at

UK ports. Our loss is no doubt Fort Lauderdale’s and Miami’s gain.

After breakfast on Day Four we leave the Atlantic, sailing through the Straits of Gibraltar into the Mediterranean. The Spanish coastline, edged with grey mist, is barely visible except as an undulating shadow against the skyline. By contrast, Gibraltar’s Rock rears up dramatically, every granite crag and gully brilliantly lit by the morning sun, sharply etched against the misty Spanish back-drop. Pure British propaganda. But on the starboard side, the Moroccan coastline is also sparkling in the bright sunlight, crystal clear. We squeeze between Europe and Africa and head for Piraeus .

Day 13: Thursday 11 September (9/11) In the Ionian Sea , somewhere south of the Peloponnese

The rush of port visits and excursions, morning and afternoon, has left little time for writing up the diary, and already with only one more visit to go before we return to Southampton memories of the first five ports of call have begun to fade. Whatever happened in Athens? No wonder we can’t remember: we didn’t go into Athens at all, memories of that hot, over-crowded and over-rated city from our last visit, decades ago, still fresh in our minds. So we chose the excursion to Corinth instead. My photograph of the spectacular Corinth Canal, splitting the Peloponnese from mainland Greece like a deep gash, proved to be my last with the precious digital camera (precious in the sense of expensive, too), which jammed and obstinately refused even to let me switch it off except by taking out the battery. Maddening, especially so early in what promises to be a photogenic cruise. We wander round the relatively well-preserved archaeological site of the old agora and temple of Corinth, decline to buy any tatty tourist-pottery, return to Piraeus along the barren coast road, lined on the land side by ugly modern buildings, and re-board Aurora in time for lunch. After the ship sails for Istanbul, we buy a cheap plastic camera in one of the ship’s shops. Depressing!

I last visited Istanbul, around 35 years ago, for a memorably farcical international conference of Red Cross and Crescent Societies and their governments, at which my function was to help head off any propensity that might develop for adopting a resolution supporting the Biafran separatist rebels in Nigeria and denouncing that country’s federal government for resisting them. At that time there were no bridges over the Bosporus and for the Turkish equivalent of sixpence you could get the ferry from Europe to Asia , disembarking at Florence Nightingale’s Scutari. On the Saturday of the weekend between the two weeks of the conference, the hundreds of unwilling delegates were herded into an old Roman amphitheatre, seated on the curved stone steps and subjected to a whole day of folkloric dances, performed by a different troupe from each of the hundred-and-something countries taking part in the conference, one of the least forgettable lowlights of my diplomatic career. My memories of the occasion are much sharper, even now, than those of our visit on Aurora just a few days ago as I write. We were certainly suitably awed by the Saint Sophia church-mosque-museum (I remembered, just in time before the Turkish guide said it himself, to tell J. that the St. Sophia in question was no lady but the abstract concept of holy Wisdom), and a good deal less awed by the interior of the Blue Mosque, now more tourist attraction with camera flashes going off all around like small fireworks while a very few Muslim visitors faced Mecca and prostrated themselves for the benefit of the tour groups. But both St Sophia and the Blue Mosque are magnificent from outside, and even more so from the Sea of Marmara as the ship sails into that majestic harbour, its surrounding hills spiked with minarets and bubbled with domes amid the white houses and the big new commercial buildings. The view of Topkapi, now also a museum, with its multiple kitchen chimneys, is also magnificent from the sea. As we sail past, a train comes in round the bend in the headland directly below Topkapi and disappears into the station, for so long the terminus of the Oriental Express at the end of the 3-day trip from Paris, still commemorated by the big and once-luxurious hotel just beyond the railway station, originally built for the comfort and luxury of the great train’s well-heeled passengers. I suppose their heirs are the folk who stream ashore now from the big cruise liners, a thousand or more at a time, safely sealed inside their air-conditioned coaches away from the wizened beggars, the spice-and-urine smells and the perfunctory, ritual importunings of the street tat vendors.

But the greatest, most unexpected moment of drama comes as the Aurora sets off again next morning and heads out of the Golden Horn into the Bosporus and passes under the first of the great new suspension bridges linking the European to the Asian sides of the city. An optical illusion makes it look impossible for the tall masts of the huge ship to clear the underside of the bridge: lining the rails, we gaze up and wonder if the Captain and the pilot have miscalculated the height of the water and of the ship, and whether we are going to witness a terrible rending of metal and masonry as the mast-head rips away the bridge fabric and breaks into shards. But somehow we squeeze underneath, mast-head seeming to clear the bridge by a few inches, and head on up the Bosporus past the ancient Turkish forts, the gleaming villas and summer palaces, the mosques and marinas, the smart-looking fish restaurants and coffee-shops, and out into the brooding waters of the Black Sea beyond. So on this cruise we have already viewed three continents at close quarters, and those of us who took the coach-and-boat trip over the bridge and along the shores of the Bosporus during the 24 hours while Aurora was in port have set foot in two of them.

A few evenings into the cruise, the Captain re-appears at our table—or rather we and our six Scots friends appear at his. Despite being the Captain of a major liner, an experienced ship’s officer, and an Australian to boot, he’s quite shy, rather hesitant in manner, not very good at signalling that dinner is over once we have finished our coffees and chocolates so that we may get up from the table and waddle off to the evening’s entertainment in the ship’s theatre without the embarrassment of feeling that we have pre-empted the Captain’s prerogative of indicating that we may leave the table. Yesterday evening he told us, with pride and no hint of embarrassment, that he both collected and made toy soldiers, his collection now numbering more than 3,000 little fighters, of all kinds of nationalities, historical periods and uniforms. A pedantic fellow-collector had once chided him for keeping an assortment of soldiers from different areas and periods in one box. “For God’s sake, man,” the Captain had replied, “I do this for fun.” Very endearing.

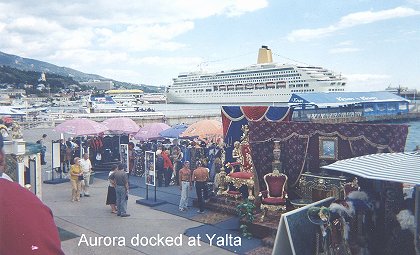

Sailing into Yalta harbour, as a raggle-taggle brass band played with immense élan on the quay to welcome us, was an oddly emotional experience for us, not just because of the implicit pathos of the welcome (implying all too few visits by western cruise ships, indeed western visits of any kind), but because it was our first return visit together to any part of the former Soviet Union since we left Moscow in 1973, after a short two years which in spite of everything had instilled in us an ambiguous but rooted affection for that now ruined and broken country and its infinitely sad, warm, sentimental people. We had chosen this particular cruise for the Yalta and Odessa visits, bursting with curiosity to find out  what had changed and what remained the same (although we knew that on such a short visit, and anyway to two cities we had never visited before, no serious comparison was possible). First impressions of the Yalta sea-front from our cabin balcony, the band going tum-ti-tum below us on the quay far below, were of a fine sea-side resort, broad promenade, lively fairground, big if somewhat shabby hotels and restaurants, background of thickly wooded pine forests on the steep hills above and around the town. Going ashore and touring the sights of Yalta confirmed these impressions: fine old public buildings, many in a state of sad disrepair, streets bustling with holiday-makers enjoying the last few days before their children were due to return to school in a dozen drab inland cities, garish posters advertising Coca-Cola and western fashion labels (replacing the old Communist Party slogans and exhortations). Little evidence of the communist era seem to have survived, apart from the evident public poverty: the once well-hidden private affluence of the nomenklatura, the old privileged Party élite with their secret hard-currency shops and private dachas, now appear to have been replaced by a brazenly flaunted affluence enjoyed, apparently, by a favoured few, mainly young, expensively dressed Yalta-ites, including the tall and proudly striding young women in sensationally provocative and suggestive clothes which made the day for some of the ageing males ashore from Aurora. The gap seemed symbolised by the numerous cars parked on both sides of the narrow streets and broader boulevards: two-thirds elderly Zhigulis and Ladas, one-third BMWs and Mercedes, even one Lincoln Continental. Welcome to capitalism, Yalta!

what had changed and what remained the same (although we knew that on such a short visit, and anyway to two cities we had never visited before, no serious comparison was possible). First impressions of the Yalta sea-front from our cabin balcony, the band going tum-ti-tum below us on the quay far below, were of a fine sea-side resort, broad promenade, lively fairground, big if somewhat shabby hotels and restaurants, background of thickly wooded pine forests on the steep hills above and around the town. Going ashore and touring the sights of Yalta confirmed these impressions: fine old public buildings, many in a state of sad disrepair, streets bustling with holiday-makers enjoying the last few days before their children were due to return to school in a dozen drab inland cities, garish posters advertising Coca-Cola and western fashion labels (replacing the old Communist Party slogans and exhortations). Little evidence of the communist era seem to have survived, apart from the evident public poverty: the once well-hidden private affluence of the nomenklatura, the old privileged Party élite with their secret hard-currency shops and private dachas, now appear to have been replaced by a brazenly flaunted affluence enjoyed, apparently, by a favoured few, mainly young, expensively dressed Yalta-ites, including the tall and proudly striding young women in sensationally provocative and suggestive clothes which made the day for some of the ageing males ashore from Aurora. The gap seemed symbolised by the numerous cars parked on both sides of the narrow streets and broader boulevards: two-thirds elderly Zhigulis and Ladas, one-third BMWs and Mercedes, even one Lincoln Continental. Welcome to capitalism, Yalta!

We spent much of the morning in the footsteps and eventually in the former home, lovingly preserved in the old Soviet (or, rather, Russian) manner, of Chekhov, who lived in Yalta for thirteen months and wrote some of his plays and stories here. After we had reverently toured the Chekhov house to the commentary of the usual touchingly besotted guide, admiring the room with the ancient piano where Rachmaninov, Chaliapin and many other legendary figures had visited and played or sung with the melancholy doctor, we were taken to a small, bare lecture-room where a tall, statuesque, handsome young woman sang Russian songs to us in a strong, thrilling contralto voice, accompanied on a battered piano by a small, harassed, middle-aged lady experiencing serious trouble managing her sheet music. The sweet, sad, nostalgic Russian music brought real tears to our eyes, accentuated by the pathos of this talented and superbly musical singer reduced to singing in honour of Anton Chekhov to a handful of tourists from a cruise ship in a Ukrainian sea-side resort, an unmistakeably surreal cameo.

The afternoon visit to the Livadia Palace in the hills above Yalta, where Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill had met in 1945 to decide the shape of post-war Europe, just a few short weeks before Roosevelt’s death and Churchill’s defeat at the hands of the British electorate, was fascinating but a lot less nostalgically moving. The handsome palace is well looked after and the rooms used by the Big Three war leaders nicely  preserved, with many photographs and contemporary press cuttings to remind visitors of those world-shaking events. We saw the room where, according to our guide, Stalin and Roosevelt had conspired together without Churchill’s knowledge to draw the boundaries of their respective spheres of influence (and, no doubt, to agree on ways to prevent the resurrection of the British Empire), later presenting a deeply suspicious Winston, by now the junior partner with no useful cards in his hand, with a string of faits accomplis. Some of our fellow-cruisers grumbled at this national humiliation and the betrayal of our alliance by the ailing American, but in truth the military realities would have ensured an outcome on broadly these lines whatever the old men in Yalta might have agreed over their vodkas and blinis.

preserved, with many photographs and contemporary press cuttings to remind visitors of those world-shaking events. We saw the room where, according to our guide, Stalin and Roosevelt had conspired together without Churchill’s knowledge to draw the boundaries of their respective spheres of influence (and, no doubt, to agree on ways to prevent the resurrection of the British Empire), later presenting a deeply suspicious Winston, by now the junior partner with no useful cards in his hand, with a string of faits accomplis. Some of our fellow-cruisers grumbled at this national humiliation and the betrayal of our alliance by the ailing American, but in truth the military realities would have ensured an outcome on broadly these lines whatever the old men in Yalta might have agreed over their vodkas and blinis.

On the floor above the Yalta Conference rooms and suites, we were led round the Tsar’s Royal Apartments, where the last of the Tsars, Nicholas II, and his family had stayed on holiday on just four occasions between the building of the Livadia Palace in 1911 and the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. The walls of the rooms are covered in framed photographs of the Tsar and his family and retainers and body-guard troops, the rooms themselves filled with much of the original furniture and decorations, the fine china they had used, the original chandeliers; our guide became increasingly lyrical in praise of the royal family as she drew our attention to the beauty of the four daughters and the good looks of the little boy, praising the way the young women had played an active part in the war effort by nursing wounded soldiers back to health. “They were doing so many good things, but then… well, events… what a family! What we have lost!” Answering our questions, she said the photographs, furniture, chandeliers and other memorabilia in the Livadia royal apartments had mostly been recovered from museums and collections to which they had been scattered after the palace had been looted and its valuable contents stolen and dispersed during the Revolution. We wondered how the guide, perhaps in her late thirties, born and brought up in the Soviet system in which the Tsars and Tsarism were either unmentionable or else reviled in the nursery language of Stalinist communism, had acquired such a detailed knowledge and affection for that beautiful, doomed family: had they been passed down orally from her parents or grandparents, or had she acquired them from her reading? That was one question we couldn’t put to her.

On the way back to the ship, we remarked to our guide on the exclusively Russian flavour of our day in this Ukrainian resort: Russian spoken in the streets and on the posters and signs, Russian culture celebrated at the Chekhov house and in the music sung for us, Russian patriotism celebrated at the Livadia—not a hint of anything Ukrainian. Ah, but remember, replied the guide, Yalta was Russian until Khrushchev gave it to Ukraine; the great majority of the population of Yalta, indeed of the Crimea generally, were Russians; and anyway Russia and Ukraine were really of the same basic culture. I thought of Kiev, the capital of Ukraine, visited with a colleague from the British Embassy some time in 1972, saturated in Ukrainian nationalism even in those far-off Soviet, cold war days, but then recalled the evening during that visit when the two of us had spent a whole evening having dinner at a huge shabby restaurant on the big broad main street of Kiev, Khreschatik, and our table companion, a Ukrainian welder from the local steel works, getting more and more drunk and tearfully eloquent as he consumed more and more carafes of ice-cold vodka and merely toyed with his pirozhki and borscht, declaimed reams and reams of Pushkin to us, in between visits to the dance floor to jive with young women in old-fashioned party frocks and badly dyed hair, one after another hi-jacked, protesting, by the welder from their tables. Russian? Ukrainian? Probably both. Russia and Ukraine seem to us to belong together as naturally as Ethiopia and Eritrea, both pairs of partners perversely but surely only temporarily sundered.

As we cast off from the Yalta quay and slowly glided out from the harbour into the Black Sea, hundreds upon hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people lined the quays and promenade and shores of Yalta to see us off, waving and shouting, as the same brass band played us away with their familiar oom-pah-pah, winding up with the inevitable tear-jerking ‘Kalinka’ to stir our nostalgia once more. We wondered why our departure had attracted so many spectators. The Captain told us later, at dinner, that Aurora was much the biggest ship ever to have docked at Yalta: hence the excited crowds. That too seemed somehow sad.

The mention of Pushkin leads us on directly to Odessa .

Day 14: Friday 12 September: In the Mediterranean between Sicily and Majorca

The coastline east of Odessa harbour as we steamed in towards the port in the sunlit early morning of Tuesday was hooded by an orange industrial mist, fed by smoke from squat factory and refinery chimneys. The implications for the discharge of effluent in the opposite direction, into the Black Sea, were thought-provoking. But the harbour itself was handsome, dominated by a tall blue skyscraper slab of new hotel, a ship-shaped quay of port buildings, and immediately in front of where Aurora tied up, Eisenstein’s Steps, looking shorter and less steep seen from the cabin balcony 500 yards away than they do in Battleship Potemkin, longer and steeper when viewed at close range from the top or the bottom. The original 200 steps have been truncated to 192 by the building of a main road and railway line running along the edge of the harbour between the bottom of the steps and the dark water of the port, thus destroying the image of steps running straight down to the sea. The track for a small funicular railway running up the western edge of the steps hasn’t been in use for many years, and even if it were to be restored now, the two small cabins, both rusting at the top, wouldn’t be able to descend to the bottom because a small bridge has unaccountably been built halfway down across the funicular. Still, the steps occupy a spectacular position both geographically and in cinema and mythological history. It wasn’t easy to establish the precise facts surrounding the eventual fate of the Potemkin mutineers and their civilian supporters at Odessa, as portrayed by Eisenstein: one of our tour guides said they had been sent into exile in Siberia and the leaders executed, another that they had escaped and been given asylum in Romania.

Odessa resembles Yalta in many ways, but on the larger scale of a major port and industrial city and without the background of pine-covered hills. In Yalta we had visited the reverently preserved house where Chekhov had lived for just over a year: in Odessa, Pushkin ditto, even down to the musical entertainment, this time by a soprano and baritone of the Odessa Opera Company, singing with rich, full voices arias from operas based on Pushkin poems. Later we visit the Odessa Opera House, built on classical European opera house lines and scale, with a vast stage and masses of dark red velvet and gilt, but in a sorry state of disrepair, with cracked and peeling walls, crumbling stairs and floors, the velvet of the seats worn almost completely away, horrendous toilets. “Restoration” has been, we were told, in progress for more than six years but it is constantly hampered by lack of funds, deterioration proceeding faster than the remont. The whole building has begun to sink into the cavernous catacombs beneath, created by the excavation of limestone for the city’s buildings, and before the internal remont could begin it was necessary to pump millions of tonnes of liquid glass into the foundations to arrest the subsidence. One tour group watched the performance of a ballet version of ‘Carmen’ on the big stage with an energetic orchestra, all ruined by the constant din of pneumatic drills somewhere off-stage.

As in Yalta, the city’s culture and language seemed overwhelmingly Russian, not noticeably Ukrainian at all. Again we ask one of the local tour guides about this. Was there any significant demand locally for reunion with Russia? The guide meditates for a moment, and decides not to answer directly. “We owe Russia so much money,” she says. “It’s a big problem for us.” Marriage, or even re-marriage, to your creditor is one solution to a nagging debt problem.

Even in the much bigger port of Odessa, Aurora’s arrival, presence and departure were evidently big events, filmed from the top of the blue slab hotel on the quay and watched by large crowds. Almost immediately after Aurora had berthed on her first ever visit to Odessa, the city’s Mayor came aboard and presented to the Captain, along with bottles of Ukrainian vodka and other souvenirs, a 2004 calendar illustrated by a full-colour photograph of Aurora tied up at the Odessa quay, a nice gimmick, the Captain thought, designed to demonstrate Odessa’s state-of-the-art technology.

Casual conversation on board, especially at the breakfast and lunch tables where there is free seating and one’s likely to be sitting with different fellow-passengers at each meal, is almost entirely confined to comparing notes about the respective merits and defects of the various cruise lines and ships. We, on only our third cruise, are raw novices. Several of those we have talked to are on their 38th, 40th, 45th cruises. At least one couple are on their third cruise this year. Very few give the impression of unlimited wealth, or even above-average affluence, yet many occupy seriously expensive cabins, gamble away big money in the ship’s casino every evening, and sit at one or other of the ship’s 12 bars for hour after hour drinking inventively concocted Technicolor cocktails at three or four pounds sterling a time. Some are accompanied by small children and ancient parents. Predictably, there seems to be no correlation between apparent affluence and social class, unless it’s a negative one. Almost everyone is a mine of information about the proportion and marginal extra cost of outside cabins with balconies on any ship you care to  mention, about the availability of prawns and smoked salmon at lunchtimes on Cunard as compared with P&O ships, about the comparative styles of entertainment and port visits of American and British cruise lines, and the relative merits of the cabins on the smaller, “more intimate” ships as compared with the newer, “more impersonal” monsters. As the subjects of conversation twice or three times daily for nearly three weeks, these matters have their limitations. There’s a tacit understanding that any discussion of politics, even current events, or of sex or how anyone earns or once earned a living, is strictly taboo. The only real cause of occasional friction arises from some passengers’ deplorable habit of reserving their loungers on the sun deck by draping their towels over them and then disappearing for an hour or more while they have their breakfasts, or, later, lunch. This is categorically outlawed in each issue of the ship’s garish daily bulletin, but the practice persists. So it’s not just the Germans.

mention, about the availability of prawns and smoked salmon at lunchtimes on Cunard as compared with P&O ships, about the comparative styles of entertainment and port visits of American and British cruise lines, and the relative merits of the cabins on the smaller, “more intimate” ships as compared with the newer, “more impersonal” monsters. As the subjects of conversation twice or three times daily for nearly three weeks, these matters have their limitations. There’s a tacit understanding that any discussion of politics, even current events, or of sex or how anyone earns or once earned a living, is strictly taboo. The only real cause of occasional friction arises from some passengers’ deplorable habit of reserving their loungers on the sun deck by draping their towels over them and then disappearing for an hour or more while they have their breakfasts, or, later, lunch. This is categorically outlawed in each issue of the ship’s garish daily bulletin, but the practice persists. So it’s not just the Germans.

Days 16–18: Sunday–Tuesday 14–16 September: Eastern Atlantic , off southern Spain ; across the Bay of Biscay

Aurora passed through the Dardanelles in the late afternoon and early evening on her way from the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara , heading for Palma two days later. On the starboard side we had a good view of the Gallipoli peninsula, accompanied by an excellent, sombre commentary over the ship’s Tannoy system by the “port enhancement” lecturer, skilfully relating each segment of the shoreline to the relevant events of 1915 as we passed along it, and identifying the various monuments with their intensely moving inscriptions as they came into view. It was a sobering experience. At dinner that evening the Captain told us that an elderly passenger, a man in his sixties, had accosted him with the complaint that we had not been issued beforehand with an information pack about the Dardanelles and the Gallipoli campaign, since he had never heard of them before. This would have been reasonably understandable if the complainant had been two or three decades younger, and thus educated in the period when history teachers dismissed anything earlier than Hitler as “irrelevant” and therefore “boring”, but a man in his sixties?

Palma, capital of Majorca (which we ought to spell Mallorca , apparently, but since we continue to call Deutschland ‘Germany’ and Hellas ‘Greece’, Majorca should be acceptable enough), proved much more attractive and relatively unspoiled than we had expected. Dominated by its huge cathedral, it’s like a sort of slightly down-market Barcelona, even boasting its own Ramblas and Gaudi buildings, and the usual complement of shady courtyards, narrow alleys and flights of steps climbing behind Moorish churches, with fine shops ranging from big department stores to cosy supermarkets, the latter dispensing whisky, gin, vodka and most other classical intoxicants at slightly lower prices than those in the Duty-Free shed on the quayside where Aurora was berthed and to which the majority of her 1,800 passengers seemed to flock the moment we were allowed off. Tired of coach-bound excursions, we opted to go ashore yesterday and explore privately, using the complimentary shuttle bus that ran all day between ship and cathedral. The local tour guide accompanying the shuttle pointed out a highly recommended fish restaurant only a hundred metres or so from where the bus deposited us, so we returned there for lunch after buying our booze at a whistle-clean, thriving supermarket under the Plaça Mayor and carting the clanking bottles back to the ship (not daring to leave it until after lunch for fear that the supermarket, like most other shops, would be closed from 1.30 to 4.30, with the last shuttle bus departing from the cathedral at 5 p.m. and Aurora sailing at 6). The restaurant, on the water’s edge from which we watched the millionaires’ yachts in the marina, proved a splendid find and we ate royally: grilled turbot, mixed grilled shell-fish on an intimidating scale, and excellent Spanish white wine, lemony in colour and taste, at a laughable price. Nice, too, to be billed in manageable and by now familiar Euros and not in thousands of pesetas.

We come back on board with some sadness, knowing that this ends the last port visit of the cruise before the return to Southampton next Wednesday. Still, there are three more days at sea in which to enjoy the strange, detached and wholly unreal life afloat, enclosed in sky, sun and water, eating, basking and reading on deck, eating, reading, swimming, eating…

We haven’t been able to access the internet on the ship’s computers for days now, for reasons that aren’t at all clear. The presiding geniuses of the cyber room explain the problem variously as too much old-fashioned electronic noise in the Black Sea and its ports, too many mountains in the way of the transmissions, and climatic conditions (otherwise perfect). So the spams are mounting up and may well exceed the limit on my ntlworld.com in basket if I can’t download and delete them all soon. And there’s the irrational but nagging suspicion that someone somewhere may be trying to send us an important e-mail, and wondering why we don’t reply. However, it saves us quite a lot of money, I suppose. Surreptitiously eating choc-ices outside the buffet restaurant after lunch on our last day, we joined a frail-looking elderly woman at her table on Lido Deck who was just finishing her own choc-ice, and discovered in casual conversation that she too had been endlessly frustrated by the long periods of no internet access, especially as she had been relying on her e-mail connection for news of a new grandchild expected during the period of the cruise and for contact with her family scattered all round Europe. Formerly married to a Romanian, she took a very European view of the world. Like us, she had been reading Neal Ascherson’s splendid book The Black Sea before and during the cruise. We mentioned that I had been reading it on deck earlier in the cruise and had been accosted by the ship’s (excellent) classical pianist, Bela Hartmann, who had spotted our Ascherson book and produced his own paperback edition from his bag. In the ensuing conversation we had asked him whether his forename, coupled with a generous helping of Liszt at his first recital, indicated any Hungarian connection, but he had laughingly denied it, saying that his name Bela had been chosen by his father (who was with him) because of his fondness for Messrs Bartok and Lugosi. But our new choc-ice companion said that Hartmann was a Czech with a Sudeten German father. Quite young, plump-faced and with a big mop of blond hair and an impeccable English public school accent, Hartmann seems to us an unusually gifted and musical pianist who deserves bigger and better audiences than a hundred or so cruise passengers passing the time before dinner. He told us later in the cruise that he reckoned to do two or three cruises a year as the resident classical musician. When we remarked to the Captain one evening that we thought Bela deserved better than this, he remarked: ‘The guy’s got to eat,’ no doubt an apt reaction. Perhaps some cruising impresario or the Music Director of the Lincoln Center will talent-spot him one day and air-lift him to higher things.

It has become increasingly obvious that cruising is addictive, and that the great majority of our fellow-passengers are hopeless addicts. We have been alarmed to find ourselves sitting in the ship’s (rather good) library leafing through the great pile of cruise brochures to find something for next year that meets our demanding criteria: cabin with a balcony, bath as well as shower, a ship praised by the experienced wiseacres aboard Aurora and not dismissed as “a disaster”, a cruise line that we have heard of, port visits to places which for the most part we haven’t been to already and which look enticing, not too many evenings forced into black tie and dinner jacket, and an itinerary starting and finishing at an English port. Oh, and preferably more or less affordable. The Butlins dimension of the big-ship cruises does eventually begin to pall, but almost all the serious intellectual cruises of Swan Hellenic are ruled out by being extremely expensive and/or because you have to fly out to the start point and back from the finish and/or because they feature informative lectures by one or other of our former Diplomatic Service colleagues on the region visited, a situation potentially conducive to paralysing embarrassment. I want to go south to the sun, not north to the ice. J. would like to combine a future cruise with the more or less annual visit to New York to see daughter and granddaughters, but I don’t fancy crossing the cold grey Atlantic by sea again: once, on the old Queen Elizabeth with two small children in 1964, seems to me more than enough. OTOH (as they say), I do rather fancy a cruise around the Caribbean … Perhaps we had better decide on ten days in a gite in the north of France and try to flush the cruise virus out of our bloodstream.