Slavery and persecution: who should apologise to whom?

Slavery and persecution: who should apologise to whom?

Jane Barder

My husband is descended from a slave-owner. His great-grandfather, six times removed, was Christopher Fredrick Triebner, who in 1783 submitted his first claim to the British Government Commission enquiring into claims for losses suffered by American Loyalists. His claim included compensation for upwards of nine hundred acres of land, six hundred volumes of books, and sundry other property, “including five Negroes Viz two Men and a Woman and two Children.”

Triebner, born in Germany in 1740 and educated at Halle University, had arrived in the young British colony of Georgia in 1769 to serve as a pastor to a group of German Lutherans who had been pioneer settlers at the birth of the colony . Months after his arrival Pastor Triebner married Frederica Margaretha Gronau, daughter of Israel Gronau and Hannah Kroeher. Israel and Hannah had survived the lengthy, squalid voyage on the English ship Purysburg which had carried the German colonists from Dover to Savannah. They arrived in May 1734, less than a year after the first landing of the founding Governor and 114 settlers, 29 of whom had died in the first year. Israel Gronau, only twenty-two years old, was one of 2 pastors who had accompanied the Lutherans and led their efforts to establish themselves in their new home. Eighteen year-old Hannah, her widowed mother and 2 younger sisters, with their fellow new colonists, travelled as victims of religious persecution. The Roman Catholic Prince Archbishop of Salzburg, who still had secular as well as religious authority, in one of the last gasps of the counter- reformation, presented his Protestant subjects with a choice; either to abjure their faith, or leave the city within two weeks. In snowy November 1731, 20,000 Protestants were expelled. Most of them were able  to take refuge in Prussia but some found a patron in George II, the Lutheran King of England. He was persuaded that these hard-working people would be trustworthy pioneers for the new colony being founded with his name. In return for their pioneering efforts the colonists were promised religious freedom and the status of British subjects for themselves and their children.

to take refuge in Prussia but some found a patron in George II, the Lutheran King of England. He was persuaded that these hard-working people would be trustworthy pioneers for the new colony being founded with his name. In return for their pioneering efforts the colonists were promised religious freedom and the status of British subjects for themselves and their children.

These dispossessed people, victims of an early form of ethnic cleansing, have become known to history as the Georgia Salzburgers. Working and living in a strange and, to them, inhospitable and unhealthy environment, prey to malaria and dysentery and thousands of miles from their homeland by no choice of their own, they eventually created a viable community. In 1966, the then Roman Catholic Archbishop of Salzburg made a public request for forgiveness. Will that do as an apology to descendants of young Hannah Kroeher and Israel Gronau?

Brian Barder’s Lutheran clergymen forebears, Israel Christian Gronau and Christopher Frederick Triebner, and other pastors had substantial responsibilities in the struggling community. They received funds from The Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK), founded in 1698 to support Christianity in British colonies, and reported to the SPCK and the Francke Foundation in Halle on the progress of the schools, medical clinics and agricultural projects under their supervision.

Israel Gronau died in January 1745 after a long illness. Triebner proved a sturdier and more controversial character than his deceased father-in-law. He was an outspoken critic of the early stirrings of the American Revolution, proclaiming the need for loyalty to the Crown which had offered refuge and liberty to the Salzburgers: perhaps it was partly due to Triebner’s strong personality and influence over at least some of his flock that Georgia was a latecomer to the cause of Independence. The colony did not participate in the 1st Continental Congress of 1774 although it signed up to the 2nd Congress in 1775. During the War of Independence Triebner took an active and well-documented role in support of British military action. So with British defeat, Pastor Triebner with Frederica and their three young children joined the retreat and eventually arrived in England as refugees. Between 1802 and 1808 Triebner worked as a preacher to the large German community in the port city of Hull. Whether or not he exchanged views with William Wilberforce, Hull’s MP, we do not know; possibly so, because his son and grandson prospered in the same Baltic trade as William’s father. Until he died in Leeds in 1815 Triebner continued to preach, and he was also a prolific writer of polemical pamphlets, often of an anti-Catholic nature.

Israel Gronau, Brian’s seven times removed great-grandfather, did not own slaves: the terms of Georgia’s foundation prohibited slavery. Colonel Oglethorpe MP had persuaded the British Government of the need for a colony which would provide a defence for the Carolinas against incursions from Spanish Florida and at the same time provide a philanthropic solution for debtors in overcrowded British prisons. The loyalty of slaves could be bought by the Spanish: resettled debtors would be allocated 50 acres of land which they could work themselves and not try to reproduce the large, slave-dependent, plantations of other American colonies. An Act of Parliament in 1735 forbade slavery in the colony. These terms suited the philosophy of the German Lutherans. However, settlers soon complained that climate and disease made it impossible for them to cultivate without slave labour: they aspired to the wealth of the rice growers of neighbouring South Carolina. They repeatedly petitioned parliament for repeal of the Act; some of them abandoned their 50 acres and moved to the Carolinas. The Salzburger pastors managed to quell any incipient demand for slavery from their congregation and, like a group of Highland Scots settlers who also preferred a slave-free economy, they petitioned the Trustees of the colony to preserve the ban. But worry that a slave population would lessen defence capability disappeared with the military defeat of the Spanish and settler pressure eventually prevailed. The ban on slavery was revoked in 1750 and by 1775 there were 18,000 slaves in Georgia. So by the time Pastor Triebner arrived in the colony, the Salzburgers had apparently succumbed to temptation and he joined the ranks of the slave owners. Do his descendants therefore owe an apology to all those of African descent, even though the presence of the Salzburgers in North America had been so cruelly enforced?

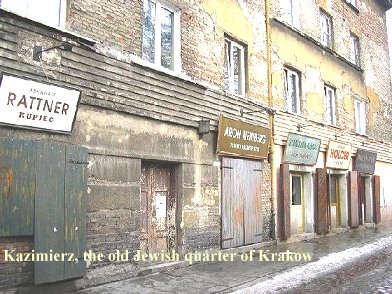

If so, some might argue that the Barders also have a claim to apology because of their Jewish descent and the sufferings of their ancestors and relatives. Brian’s mother was one of Pastor Triebner’s descendants. His crusading religious beliefs and the sufferings of the Salzburgers had long been forgotten by the time Vivien Young, daughter of Vivienne Triebner, married Harry Barder in 1933. Vivienne’s parentage was maternally Quaker and paternally Catholic. But Harry Barder’s heritage was wholly Jewish: he was born in 1883 into an orthodox Jewish family. His grandparents, Louis (Nachem Lazar Bader) and Hannah (Chaia Hamburger), had migrated to England from the Jewish quarter of  Cracow in about 1852 and Levy, his father was born in London in about 1853. The Baders came from a large family in Cracow, their name originating from a grandfather’s important community role as the bath-house keeper, barber, and paramedic. They were linked by marriage to numerous Cracow families. Those who had not emigrated are listed among those who died in Auschwitz. Brian’s father could not be said to have mourned the kissing cousins he had never met, but throughout the second world war he, justifiably, feared his certain fate and the fate of his son if Britain were to lose. Does this deserve an apology from someone?

Cracow in about 1852 and Levy, his father was born in London in about 1853. The Baders came from a large family in Cracow, their name originating from a grandfather’s important community role as the bath-house keeper, barber, and paramedic. They were linked by marriage to numerous Cracow families. Those who had not emigrated are listed among those who died in Auschwitz. Brian’s father could not be said to have mourned the kissing cousins he had never met, but throughout the second world war he, justifiably, feared his certain fate and the fate of his son if Britain were to lose. Does this deserve an apology from someone?

Harry’s mother, Rebecca, was born in Manchester in 1856. Her father, Abraham Waxman, or Warchavski, told his grandson that he had fled from Russian Poland, stealing a passport to do so, to avoid conscription into the Tsar’s army. Jewish families held mourning ceremonies for their conscripted sons. They were rarely seen again. Abraham did not find a fortune in England. A young widower, he and Rebecca relied on charity from Jewish relief funds. But he died in the comfortable London home of Levy, his son-in-law, living with his grandchildren around him. Perhaps he owed a debt to the Tsar for precipitating his flight from a life of much greater hardship and the prospect of death in a pogrom. Who owes whom an apology for the infliction of such hardship and danger?

London, March 2007

Who is asking you or anyone else for an apoplogy????? I am African American and I am not,how could a verbal apololgy compensate for salvery and persecution?