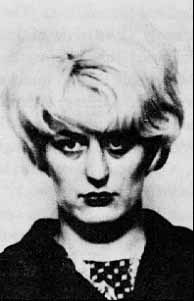

Myra Hindley

Myra Hindley: Justice, the Law, the Judges and the Politicians

A pre-script

The article below was written before Myra Hindley’s death, still a prisoner, in November, 2002. She died shortly before the hearing of a case by the Law Lords which was expected to declare that the Home Secretary’s power to extend the tariff of prisoners serving life sentences for murder set by the trial judge and the Lord Chief Justice was incompatible with the Human Rights Convention, now embodied in UK law. Such a ruling ought to have ensured that Myra Hindley would be released within a few weeks or months. But our then Home Secretary (November 2002)threatened to introduce new legislation if necessary to preserve his right to keep murderers in prison for longer than the judges have recommended: and after Hindley’s death the Manchester police disclosed that they were considering a fresh prosecution of Hindley for the two murders to which she confessed while in jail, but for which she was not originally charged or convicted. So even if Hindley had lived a few months longer, and the Law Lords had struck down the Home Secretary’s power to keep her in prison, it seems that ingenious ways would have been found to avoid having to release her as the law would have required. To such lengths will craven politicians stoop to avoid the venomous assaults of the more poisonous of the tabloid press, with their campaign of hate and menace against this by then harmless and sick middle-aged woman, and ttheir immovable determination to stoke up and keep alight the flames of vengeful vindictiveness on the part of the relatives of Hindley’s and Brady’s victims of nearly 40 years before: ensuring that those unhappy relatives are the permanent victims of the tabloids, as well as of two long-ago perverted killers. The decision on how long each individual criminal should serve in prison belongs properly to the judges, not to politicians. Myra Hindley, whose crimes nothing can ever excuse, paid a terrible price for the insistence of successive Home Secretaries on keeping, and cravenly exercising, a power they should never have been allowed to possess. It’s too late now to do anything to redress this injustice, even in part. But the way this woman was treated deserves to be remembered as an object-lesson in the absolute need to keep politicians out of areas of decision-making that belong properly to judges: and in the way politicians will pay more attention to vindictive tabloid newspapers interested only in boosting their circulation, than to basic principles of justice.

23 November, 2002

How long should Myra Hindley stay in prison?

As of now (March 2000), Myra Hindley has been in prison for nearly 35 years (she was charged on 26 October, 1965, and convicted and sentenced on 6 May, 1966). Aged just 22 at the time of her trial, she is now 57. The judge who presided at her trial, the man best placed by his judicial experience, his first-hand knowledge of all the evidence and arguments presented at the trial and his personal observation of Hindley throughout the trial, to make an objective judgement about the length of time Hindley should actually serve, wrote to the Home Office only two days afterwards that while he believed Ian Brady, whose accomplice Hindley had been, was wicked beyond belief, with no hope of redemption short of a miracle, he could not feel that the same was necessarily true of Hindley, once she was removed from his influence [evidence of Brian Masters in BBC2 television programme about Hindley, 1 March 2000. In pronouncing the mandatory sentence of life imprisonment on her, the judge (Mr Justice Fenton Atkinson) said that Hindley should remain in prison “for a very long time”: and he is reported to have recommended to the Home Office a “tariff” of 20 years [for example, Lord Donaldson, former Master of the Rolls, BBC Radio 4, The World at One, 16 January 1996: ‘It also appeared, said Lord Donaldson, that Hindley’s tariff sentence had been altered. “First, it was 20 years, then it was 30 years and then it was life.” ‘– Daily Telegraph, 17 January 1996].

The then Lord Chief Justice, Lord Chief Justice Lane, described in a recent Guardian editorial as “no softie”, then (1966) recommended that this be increased to 25 years. Lord Lane reaffirmed this advice in 1985. Thus the two judges who were best placed to decide a just and appropriate sentence at the time of the trial agreed that 20 or 25 years in prison for Hindley would be sufficient for society’s retribution against her exceptionally dreadful crimes, for the deterrence of others, and––subject to an assessment at the time––for her rehabilitation as a person who would no longer represent a threat to others.

Yet these considered views of the principal judges concerned at the time were soon overruled by the politicians, none of whom had been present at the trial, had personal knowledge of Hindley, or possessed any superior basis for a judgement of the minimum sentence required for retribution and deterrence. Her tariff was set at 30 years by the Home Secretary, Leon Brittan, in 1985, and increased again to “whole life”––meaning that Hindley should never be released, but should stay in prison until she died––in 1990 by the then Home Secretary, David Waddington. In 1997, the then Home Secretary, Michael Howard, reaffirmed the “whole life” tariff, in a decision later declared unlawful because he attempted to rule out any further review in the light of the prisoner’s conduct and character: and in November of the same year, the new Home Secretary, Jack Straw, also reaffirmed the “whole life” tariff––this time keeping just within the law by asserting that when reviewing at the 25-year point he would be open to the possibility that “exceptional circumstances”, including exceptional progress in prison, might render a reduction appropriate [see Court of Appeal (Civil Division), London, UK, 5 November 1998].

Behaviour in prison: safe to release?

As early as April 13, 1985, 20 years after she had gone to prison, the first review of Hindley’s case, by a local review committee, recommended her release to the Parole Board. As we have seen above, successive Home Secretaries have overruled that recommendation. Yet it was implicitly renewed by the Parole Board’s recommendation on 9 February, 1996, that Hindley should be moved to an open prison––usually the preliminary stage before release on parole or licence. Father Bert White, who was at one time her prison chaplain and who has kept in touch with her since that time, has testified that “the person [Myra Hindley] I know today … is not an evil person” [BBC2, 1 March 2000]. As mentioned above, the judge at her trial recorded his view that Hindley should be capable of redemption once removed from Brady’s influence.

Geoff Knupfer, a former Detective Chief Superintendant (now retired) who was responsible for the investigation of the murders and the interrogation of Brady and Hindley, has stressed the degree to which Hindley was acting under Brady’s powerful influence. He saw no reason to doubt that if Hindley had never met Brady, she would have led an ordinary life, marrying and having a family like any other woman of her background [BBC2, 1 March 2000].

Same degree of guilt as Brady?

Even the prosecuting counsel at Hindley’s trial, Elwyn Jones QC, accepted that she had been “indoctrinated” by Brady, and that she was an accomplice, not a perpetrator. No evidence has ever been produced to prove that Hindley herself committed any of the five murders herself, although she obviously collaborated actively with Brady in carrying them out: at the original trial, Brady was convicted of all three murders with which both of them had been charged, but Hindley was acquitted of one of them. Lord Justice Lane, in setting Hindley’s tariff at 25 years, set Brady’s at 40.

Hindley’s crimes were atrocious. But Brady’s were appreciably more atrocious still. Yet the punishment set by the politicians––as distinct from the judges––makes no distinction between what is appropriate for the main perpetrator, and what is appropriate for the accomplice.

Public opinion and the victims’ relatives

Majority public opinion has always been strenuously opposed to the release of Hindley at any time, regardless of any evidence of remorse, repentance or reformed character, and whether or not she would constitute a threat to anyone if released. According to a poll taken some 4 years ago, “A recent MORI poll shows that 77% disagree with the current policy that prisoners serving life sentences for murder may be released after a certain period of time. This figure increases to 83% when asked if Myra Hindley, who received a life sentence and has now served 31 years imprisonment, should be released from prison.” [Myra Hindley, Great Percy Productions Limited] Other polls have produced similar results. The tabloid press has consistently and emotionally encouraged public opposition to any idea of Hindley ever being released, whatever the circumstances.

Brady’s and Hindley’s victims’ relatives, regularly interviewed by the electronic and print media whenever any question of Hindley’s release has cropped up, have––much more understandably––expressed literally violent opposition to any thought of Hindley ever being released, at least two of the bereaved parents insisting that Hindley herself would immediately be killed as soon as she was released from prison, whatever the difficulties involved in finding and identifying her. One of the parents has publicly produced a knife which he carries, as he asserts, to use to kill Hindley if ever he is given the chance. Another says she would hunt her down if it took her the rest of her life to do it.

According to the Daily Telegraph, quoting a cleric and former prison governor, ‘the Rev Peter Timms, a south London Methodist minister who has taken a keen interest in her case, described Mr Howard’s decision as “disgraceful”. Mr Timms… said: “The Home Secretary’s decision to give a natural life tariff in the case of Myra Hindley is a gross injustice. It treats her differently to every other life-sentence prisoner and it’s now clear that she is a political prisoner.” He said it was a sad reflection on the system of justice that one woman had been singled out because of “concerted adverse publicity over 30 years”. The decision to keep her in prison without any justification under normal rules had been taken “for no other purpose than votes”. Mr Timms added: “She is not dangerous and every report on her has confirmed that for almost 20 years. This is an injustice, and injustice for one in a civilised society is injustice for all, and ought to be resisted by all thoughtful people.” ‘ [Daily Telegraph, 5 February 1997]

Why one Home Secretary––the Conservative Leon Brittan––should have decided in 1985 that a 30-year tariff satisfied the needs for deterrence and retribution, while from 1990 onwards two later Conservative Home Secretaries and one Labour took the radically different view that only imprisonment for the rest of Hindley’s natural life would suffice, cannot easily be explained. It can hardly be argued that between 1985 and 1990 Hindley had become massively more wicked, or her crimes somehow even more abhorrent to society, or its criminals so much more hardened that a fiercer deterrent was now required. It seems likelier that as the time for possible release came nearer, successive Home Secretaries funked the responsibility of releasing her, for fear of incurring the wrath of the victims’ relatives, of The Sun newspaper and of the man (and perhaps especially the woman) in both the Public Bar and the polling booth.

How much weight should be given to public opinion?

“It is this last question that Aeschylus asks most insistently in his two most famous works, the Oresteia (a trilogy comprising Agamemnon, Choephoroi, and Eumenides) …: is it right that Orestes, a young man in no way responsible for his situation, should be commanded by a god, in the name of justice, to avenge his father by murdering his mother? Is there no other way out of his dilemma than through the ancient code of blood revenge, which will only compound the dilemma? … At the command of the Delphic oracle, Orestes journeys to Athens to stand trial for his matricide. There the goddess Athena organizes a trial with a jury of citizens. The Furies [Eumenides] are his accusers, while Apollo defends him. The jury divides evenly in its vote and Athena casts the tie-breaking vote for Orestes’ acquittal. The Furies then turn their vengeful resentment against the city itself, but Athena persuades them, in return for a home and cult, to bless Athens instead and reside there as the “Kind Goddesses” of the play’s title. The trilogy thus ends with the cycle of retributive bloodshed ended and supplanted by the rule of law and the justice of the state.” [Encyclopaedia Britannica]

The Oresteia was presented in Athens in 458 BC, nearly two-and-a-half thousand years ago. It seems that there are some lessons which each generation is doomed to learn afresh.

The desire for vengeance on the part of people whose children have been murdered in unimaginably obscene ways is completely understandable, as indeed is the inflammation of public opinion with the same blood-lust by a tabloid press, our modern unreconstructed Eumenides, whose sole concern is circulation and profit. But as Aeschylus showed in dramatic form 25 centuries ago, there does exist a better way: to substitute for emotional revenge the cool and objective judgement of established courts with fair procedures and with judges trained to apply the cool criteria of law and justice, unswayed by mob emotion or by the instincts of those whose judgement is distorted by rage and grief. The tariffs for Hindley’s incarceration deemed proper by successive judges (and by one solitary Home Secretary)––20, 25, 30 years––already encompass the law’s acceptance of society’s right, not only to deterrence, but also to retribution (however much some of us might question whether this is indeed an acceptable and justifiable element in punishment). Yet Hindley has already served in prison almost half a decade beyond the most severe tariff set by any judge. Only the politicians insist that this now elderly and sick woman can never repay her debt to society and that she must stay in prison until she dies. Can it really be said that this politicians’ sentence is dictated by a more profound sense of justice than that of the judges, and not by fear of the public and press reaction to what ought now to be done?

Conclusions

No conceivably proper purpose is served by keeping Myra Hindley in prison any longer. On the severest judicial reckoning, she has been more than sufficiently punished to satisfy society’s felt need for retribution and the clear need to deter others. No-one argues that she any longer represents a threat to society if released: the only threat is that posed by parts of society to her. On the evidence of those who know her, she is a quite different person from the 22-year-old who fell under Brady’s malign spell and committed such inconceivably horrific crimes. She continues to be punished, not for any defensible reason of logic or justice, but because successive Home Secretaries are frightened of the reaction of public opinion, as pumped up by parts of the more malodorous media, to her release––a reaction capable of being expressed in votes as well as in protests and invective.

The icon of hatred

It is argued by some that such decisions as whether, and if so when, to release notorious and much hated murderers from prison, are properly the responsibility of politicians who can be called to account for them to Parliament and ultimately to the electorate. Such a pre-Aeschylean attitude implies that a cool, calculated, judicial view, based on the facts and the law, should be outweighed by the gut feelings of a public which is inevitably for the most part innocent of any detailed knowledge of the factors to be taken into account, of the personalities of those most closely concerned, of the law’s definitions of the purposes of punishment, of the fine gradations and degrees of guilt revealed in long and long-ago trials, and of the absolute necessity of setting aside private emotion and the desire for revenge. There is an obvious need for a minister to have the power to reduce or cancel the sentence of a court, for example when evidence of a miscarriage of justice requires an immediate remedy: but no obvious justification for empowering any politician actually to increase the severity of a sentence, once pronounced by a court, nor of the considered decision of a Parole Board.

Society’s right to express its view of how particular crimes ought to be punished is fully satisfied by parliament’s power to decide in its laws the minimum and maximum penalties to be made available to the courts for specific crimes, and the factors to be taken into account by the courts in matching specific penalty to specific crime. Those who make such laws, the ministers who propose them and the elected parliamentarians who adopt them, are rightly held accountable to public opinion, through the media and at election time. Decisions on how the law should be applied in individual cases need to be taken out of the hands of politicians and placed where they belong: with the judges, and with the Parole Boards: perhaps advised by a new body including the judiciary, prison governors and Visitors, Parole Boards and probation officers. If such an obviously desirable reform had been adopted at any time in the last two decades, Myra Hindley would not now be in prison, and our society would not now be stained by such a manifest injustice.

If a Labour government is unwilling to grasp this nettle, what future government will?

London

5 March 2000