In memoriam Alan Sillitoe, 4 March 1928 – 25 April 2010

The novelist, poet, playwright and Nottinghamian Alan Sillitoe died, age 82, in the early hours of yesterday morning. I am a second cousin of his wife, now widow, the poet Ruth Fainlight, and my wife J. and I have got to know Alan and Ruth well in recent years: and as the song almost says, to know Ruth and Alan is to love them. We last saw them both just two weeks ago in their book-laden flat. Alan, already gravely ill, was as usual his smartly dressed, chipper, friendly and sharply observant self — he went down to the kitchen and made the coffee, and we all sat round chatting about the election and other things. I told him that he looked far better than we had dared to hope: “You’re indestructible, Alan,” I told him. “I hope so,” he replied, perhaps (in retrospect) a little grimly. Well, it turns out that he wasn’t. But his books and his reputation certainly are.

His Guardian obituary today, informative and affectionate, is required reading. News of his death was in all the television and radio bulletins yesterday and is on the front pages of several newspapers today: this may seem to some a little surprising, but should not be. He was a great writer and a lovely man.

In memory of Alan Sillitoe I am reproducing below my blog post of February 2008, written to celebrate his 80th birthday. And in celebrating Alan’s life and work, we should also think of Ruth, his friend, muse, companion and wife of 60 years, and of their children, David and Susan.

In celebration of Alan Sillitoe at 80

February 28th, 2008

On 4 March 2008, next Tuesday, Alan Sillitoe will celebrate his 80th birthday, and tens of thousands of other people the world over should be celebrating it too. Everyone remembers him for those early masterpieces, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, two works that changed the English fiction landscape for ever and whose film versions, with Alan’s screenplays, are imprinted on the minds of everyone over 40 (and many younger too). Alan Sillitoe has so far written (I calculate) 79 other books besides those two: more than one book for every year of his long life; all published in the half-century from 1957 to 2007, this works out at just over one-and-a-half books a year, a truly Stakhanovite record — and the other good news is that he’s still writing and seems set to continue writing for at least another half-century. His versatility is also very remarkable: the books include (in addition to the prolific fiction) autobiography, writings for children, plays, essays, poetry, screenplays, short stories, and travel. His bibliography on the Web is extraordinarily impressive. Many of his books have (unsurprisingly) won literary awards.

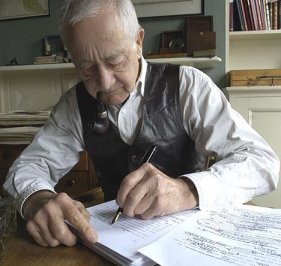

As this picture shows, Alan does most of his writing by hand, so it’s the more remarkable that he is also an expert amateur radio ham, including a reader and tapper-out of Morse Code, as well as a devoted collector and connoisseur of maps, activities descended from his service in the RAF in Malaya. He has lived at various times in various places in Europe and north Africa; now a Londoner, but still unalterably nourished by his Nottingham roots: how appropriate, then, that he is shortly to be made a Freeman of the City of Nottingham (which, I’m told, will give him the right to drive a flock of sheep through the centre of town). He’s an undaunted but highly discriminating man of the left. He has too a distinguished academic record: Visiting Professor of English at Leicester de Montfort University (1994-7), Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and of the Royal Geographical Society, and an Honorary Fellow of Manchester Polytechnic (1977). He has been awarded honorary doctorates by Nottingham Polytechnic (1990), Nottingham University (1994) and De Montfort University (1998).

As this picture shows, Alan does most of his writing by hand, so it’s the more remarkable that he is also an expert amateur radio ham, including a reader and tapper-out of Morse Code, as well as a devoted collector and connoisseur of maps, activities descended from his service in the RAF in Malaya. He has lived at various times in various places in Europe and north Africa; now a Londoner, but still unalterably nourished by his Nottingham roots: how appropriate, then, that he is shortly to be made a Freeman of the City of Nottingham (which, I’m told, will give him the right to drive a flock of sheep through the centre of town). He’s an undaunted but highly discriminating man of the left. He has too a distinguished academic record: Visiting Professor of English at Leicester de Montfort University (1994-7), Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and of the Royal Geographical Society, and an Honorary Fellow of Manchester Polytechnic (1977). He has been awarded honorary doctorates by Nottingham Polytechnic (1990), Nottingham University (1994) and De Montfort University (1998).

Meeting this sharp, observant but strikingly unassuming and friendly figure, you’d never guess that he’s what the tabloids would call a legend in his own lifetime: a writer whose style is so deceptively clear and simple that you’d easily miss the artifice and skill that lies behind it. A review of one of his books in the Guardian, published in 2004, gives an excellent impression of him.

Not least, he’s the devoted and long-time husband of the distinguished poet Ruth Fainlight, of whom I’m proud to be a second cousin — as well as an admiring and affectionate friend of this amazingly productive and beautiful couple.

Happy birthday, Alan, and many more of them: all, let’s hope, still at an average rate of a book and a half a year!

Brian

Alan Sillitoe wrote an introduction to my copy of “The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists.”

He first read it, he says, during his RAF service when he was given an abridged copy by a wireless operator who told him that, “Among other things it is the book that won the ’45 election for Labour.”

AS didn’t bother to cavil.

I’d love to know the thoughts of Frank Owen, Robert Noonan or indeed of AS himself about today’s top socialists – men like Lord Kinnock, Lord Mandelson, Mr Blair and Mr Brown.

Brian writes: Thanks, John. My impression is that Alan Sillitoe was not a great admirer of the majority of today’s Establishment politicians.

I met Alan Sillitoe several times in London. The first time in summer 1975, the last time exactly 30 years later. He was always a most kind man, showing great patience with the Swedish interviewer, and also kind enough to furnish me with some really nice editions of his books.

As a writer he will be remembered for much more than his early works. I admire his poetry and his books of travels; I recommend his poems to all those that think of him as only a prosewriter. He was much more than that.

Brian writes: Thank you very much for this contribution, which I am passing on to Alan Sillitoe’s widow, the poet Ruth Fainlight.

I met Ruth Fainlight a couple of times, the first time in the summer 1975. That was the first time also that I met Mr Sillitoe. I vividly remember how he showed me his radio taken from a Lancaster bomber plane. He tuned in the conversation between North German fishing boats off the coast of Germany.

Meanwhile his wife kindly wrote down, inm my album of literary autographjs, a long poem of hers.

Brian writes: Thank you very much for this. Further evidence of the great kindness — the prince of virtues — of this remarkable and beautiful couple. I am passing your reminiscence on to Ruth.

Did any postwar English novelist write a book as self-searching and outward looking as RAW MATERIAL? It was a glimpse into Alan Sillitoe’s workshop. I found it as fascinating as looking inside the workroom of Hentry Moore or Benjamin Britten. Sillitoe was the most English of writers and yet the most European. The Wain Braine Amis Larkin group were too insular for my taste. Sillitoe was without frontiers as well as without armour. Let’s ignore the London metropolitan trendies. He got better as he got older. Take a look at THE WIDOWER’S SON, HER VICTORY, THE OPEN DOOR. They are books you want to give away. Then you wish you could read them again. His eye for landscape, whether around Nottingham or Lincolnshire, was outstanding. His essays, MOUNTAINS AND CAVERNS and A FLIGHT OF ARROWS are peppered with epiphanies. Have you noticed how weather dominated so much of his writing? There’s his short story BEFORE THE SNOW COMES, the poem sequence SNOW ON THE NORTH FACE OF LUCIFER, and the late novel SNOWSTOP. The Burmese sequence in THE OPEN DOOR sets up a kind of vibration that you can feel back in England. Sillitoe, like Stan Barstow, is in a class by himself.

Brian writes: Thank you for this eloquent reminder of the astonishing legacy of memorable writings by Alan Sillitoe.

May I be allowed to make some adjustments to yesterday’s comment? The poem sequence to which I referred is in fact SNOW ON THE NORTH SIDE OF LUCIFER. I drew attention to a ‘Burmese’ incident in THE OPEN DOOR; the scene takes place, I believe, in Malaysia. Your readers will want to consult Richard Bradford’s excellent biography of Alan Sillitoe, The Life of a Long-Distance Writer (Peter Owen, 2008). There are a couple of critical studies. One is available in paperback. An earlier work, and an extremely useful one, is Alan Sillitoe: A Critical Assessment by Stanley S Atherton (WH Allen, 1979). Just yesterday I purchased a copy of New and Collected Poems by Ruth Fainlight (Bloodaxe). In Alan Sillitoe’s autobiography, WITHOUT ARMOUR, there is an account of how they met in Majorca and were married. Ruth Fainlight’s dedication reads ‘in memory of Alan’.