Harry Barder and his ancestors

Harry Barder and his ancestors

Contents:

Harry’s mother, Rebecca

The Barders’ Krakow Origins

Krakow connections

Rebecca, Levy and the other UK-born Barders in Manchester

Moving on from Manchester

The Barders as furriers

Levy’s sisters

The Hamburgers

Harry’s siblings and his own story

Harry, father of Brian and grandfather of Virginia, Louise and Owen, was born on 21 April 1883 at 46 Whitefriargate, Hull. His parents were Levy Barder, a toy dealer, and Rebecca, formerly Waxman.

Rebecca Barder was 81 when she died in 1936, at 5 Inglewood Mansions, Hampstead, a comfortable area of London. Levy, a Master Furrier, had died in 1930, and Rebecca was the mother of five surviving children. We have a photograph of her, a companion to one of Levy and so probably taken in the 1920s. They are pictures of prosperous, middle-class people. Rebecca, dressed in Queen Mary style, wears a brooch; from her necklace a large locket hangs below her bolster bosom. Her photograph and the facts recorded on her death certificate give no hint of the privations and tragedies which dogged her early life.

Harry’s mother, Rebecca

Rebecca was born on 8 October 1855 at Berkeley Street, Cheetham, Manchester. Her father, Abraham, who “made his mark” when registering her birth, was a cloth cap maker and her mother was Anne, formerly Abrahams. We know from the three census listings we have for Abraham Waxman that he was born in Poland. It seems that he came from the Russian-ruled area of Poland (at that time partitioned between Russia, Austria and Germany) rather than Austrian Poland like the Barders. Harry Barder once said that his grandfather fled to England to avoid conscription into the Russian army and stole a passport (or in other words an identity document, compulsory in the Tsarist Empire as in the Soviet Union), to help his flight. We know that enforced conscription of Jews was one of the reasons for extensive Jewish migration between 1844 and 1851.  When Harry gave as much family information as he knew, which was sadly little, for his first grandchild’s Baby Book, he gave his mother’s name as Rebecca Warshovsky. Waxman could be an Anglicization of that: or it could be that the fleeing Abraham was Warshovsky (or, more likely, Warshawsky) and the stolen passport was in the name of Waxman.

When Harry gave as much family information as he knew, which was sadly little, for his first grandchild’s Baby Book, he gave his mother’s name as Rebecca Warshovsky. Waxman could be an Anglicization of that: or it could be that the fleeing Abraham was Warshovsky (or, more likely, Warshawsky) and the stolen passport was in the name of Waxman.

Rebecca >

I have not found a marriage certificate for Abraham and Anne. Perhaps they were married before they arrived in England, or perhaps their synagogue marriage was never officially registered. After Rebecca, the next Waxman whose birth was registered in Manchester was Simon Harris Waxman, born in March 1862 at 83, Red Bank. His parents were Abraham, a commercial traveller who once again made his mark, and Hannah, formerly Harris. Simon died early in 1863. Hyman Waxman was born in 1864 and died a few months later in 1865. In December 1865, at 11 Winter Street, Red Bank, Hannah Waxman died at the age of 33 from phtisis (TB): her death certificate states that she had suffered from this for two years. Her husband, Abraham Waxman, a hawker, was present at the death. It seems likely that Anne Abraham and Hannah Harris, both recorded as the wife of Abraham and mother of his children, were one and the same person. I can find no death certificate for Anne Waxman and no marriage certificate for Abraham and Hannah. There was probably a degree of incomprehension between Abraham and a hard-pressed Registrar when the births were registered. One fact is sure: 10-year-old Rebecca had lost her mother and two baby brothers, had lived with illness for two years and, with her immigrant father, was dependent on nineteenth-century charity. In July 1862 Abraham Waxman was prosecuted for larceny at the Quarter Sessions in Preston. So far I have not found the result of the prosecution, but life was obviously as hard as could be for the Waxman family. Records of the Jewish Benevolent Relief Fund for 1865/1866 show an application for help from Abraham Waxman, a widower with a 9-year-old daughter. His address was 11 Winter Street, Red Bank, scene of Hannah Waxman’s death.

The Red Bank area of Manchester where they lived was a crowded centre for Jewish immigrant settlement. It had been a middle-class district until the building of the railways and then Jewish migrants were attracted by spacious cheap houses suitable both as workshops and homes. Bill Williams, writing “The Making of Manchester Jewry” in 1976, described it thus:

The heart of a voluntary ghetto, most streets unlit, drains choked by the lie of the land, wells tainted and air polluted by pestilential effluent from the Irk, loaded with manufacturing refuse and decomposing matter.

Cap-making, according to Williams, was the boom industry of the late 1840s and 1850s, using unskilled labour and appealing to a mass market. This was Abraham’s occupation at the time of Rebecca’s birth. I haven’t found him in the 1861 Manchester census: perhaps he was in prison, awaiting trial. In the 1871 census he and 15-year-old Rebecca were living at 11 Davison Street, Manchester. Abraham was described as a Marine Store Dealer. By 1881 Rebecca was already married. Abraham was a lodger at 5 New Street, Cheetham, a General Dealer and in 1891, still a General Dealer, he was a boarder in Robert Street, Manchester. On Rebecca’s 1875 marriage certificate he is more grandly noted as a merchant, like Eleazer (sic) Barder, father of the groom. When Abraham died in 1895 his occupation was noted as “Formerly a Dealer in Crape and Horse Hair”. ‘Crape’ is an alternative spelling for ‘crepe’ and is specifically used in connection with mourning clothes. It would seem therefore that Abraham’s last occupation involved burial rites, perhaps Jewish.  His death was registered by his son-in-law, Levy Barder, and his final home was with Rebecca and Levy at 182, Edgware Road, London. Harry Barder was 12 in 1895 and must have heard from his grandfather the story of his flight from Russian Poland and the change of name from Warshavski. Levy and Rebecca had married in 1875 at The Great Synagogue, Prestwich. Both gave their address as Frances Street, Cheetham. It must have seemed that Rebecca could expect some improvement in her circumstances when she married Levy Barder, a draper. But Rebecca had more troubles to face. In October 1876, just over a year after her marriage, she had a prematurely born daughter who lived for only three hours. This was at 1 Brighton Terrace, Bethnal Green: Levy was making an early attempt to be a furrier. Eight months later at 31 Robinson Road, Bethnal Green, she had another premature baby, a boy who lived for an hour. After another eight months, in January 1878, at 8 Victoria Park Road, Hackney, a third child was born. They called him Harry but he died when he was two hours old. However, her life did improve. Although the Barders were still first generation immigrants with many more moves and changes of occupation still to come, by 1875 they were already a large family, apparently combining their efforts in various business enterprises. Levy’s parents, Louis and Hannah Barder, had arrived in England from Krakow, Poland, around 1853.

His death was registered by his son-in-law, Levy Barder, and his final home was with Rebecca and Levy at 182, Edgware Road, London. Harry Barder was 12 in 1895 and must have heard from his grandfather the story of his flight from Russian Poland and the change of name from Warshavski. Levy and Rebecca had married in 1875 at The Great Synagogue, Prestwich. Both gave their address as Frances Street, Cheetham. It must have seemed that Rebecca could expect some improvement in her circumstances when she married Levy Barder, a draper. But Rebecca had more troubles to face. In October 1876, just over a year after her marriage, she had a prematurely born daughter who lived for only three hours. This was at 1 Brighton Terrace, Bethnal Green: Levy was making an early attempt to be a furrier. Eight months later at 31 Robinson Road, Bethnal Green, she had another premature baby, a boy who lived for an hour. After another eight months, in January 1878, at 8 Victoria Park Road, Hackney, a third child was born. They called him Harry but he died when he was two hours old. However, her life did improve. Although the Barders were still first generation immigrants with many more moves and changes of occupation still to come, by 1875 they were already a large family, apparently combining their efforts in various business enterprises. Levy’s parents, Louis and Hannah Barder, had arrived in England from Krakow, Poland, around 1853.

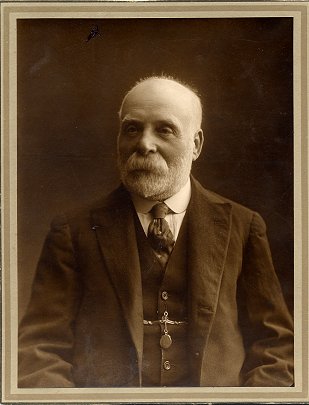

Levy Barder ?

The Barders’ Krakow Origins

There are a surprising number of surviving records for Jewish Krakow families[1], many of them microfilmed by the Latter Day Saints: and, since 1995, increasingly available on http://www.jewishgen.org/. In recent years it has become possible to do a lot of research on the internet, largely because of the goodwill of devoted Jewish researchers who have produced indexes and translations freely available to all. Initially, however, in this search for Barders and before the internet had burgeoned into a family history research goldmine, it was Dick Barder, great-grandson of Arnold Barder, one of Louis and Hannah’s UK-born sons, who followed up a family belief about the Barders’ origins and approached the Krakow archives for help. He was rewarded with the following (in translation):

“In July 1852, at 10 o’s clock in the morning, Leibel Hamburger, factor 3/2, 68 years old, lived at number 189, the grandfather of the baby (he showed the baby: “sex – male” ) who was born on 14 July 1852 at 6 o’clock in the afternoon at his parents’s flat, who was the fruit of love of Lazar Barder (23 years old) and Hala Hamburger (22 years old) and they gave the child the name Izrael.”

The unusual phrase “fruit of love” and the fact that the child was presented by his maternal grandfather might mean that Izrael was born before his parents, known to us as Louis and Hannah, were married, but the baby was registered as Bader. Perhaps it was the reason why Louis and Hannah left so soon after his birth. But, if so, there was no long term family rift: we know that they made at least one, possibly two, return visits to Krakow and the family home.

Hannah’s parents were Leibel Isaac and Breindel Eliasz who married in Krakow in February 1804, although the surname Hamburger does not appear in the marriage index. Only after the Austrians took control of Krakow in the 1795 Partition of Poland did they decree that Jewish families should assume surnames instead of identifying themselves through their fathers’ names. Thus Leibel was the son of Isaac, who died in Krakow in 1834, and Isaac was the son of Fiszel. We see this in the 1790 census, enumerated by Rabbis in the last years of Polish rule, before the introduction of surnames. Here Leibel appears as Lewek, 8 years old living in house number 56 with his parents, Icek Fislowicz, aged 30 and Gitla Israel, aged 27. Research becomes much easier from about 1805 onwards when surnames came into use. The first of Leibel and Breindel’s children to be listed as Hamburger was Israel Hirsch, born in December 1806. I believe that Hannah was Haile Gitel Hamburger, born in 1826 and thus somewhat older than 22 when her first child, Izrael Bader was born in 1852. There are later Krakow marriage or death records for all of Leibel and Breindel’s children except for two who disappear from Krakow records. Haile was one, the other was Menasses who was born in 1823. Like his sister, he migrated abroad. He went first to Paris where in 1846, as Marcus Hamburger, a jeweller, he married Jeanette Levy who died in 1849, leaving two young children. Some time in 1860 Marcus Hamburger with his second wife and three children arrived in England where three more children were born to them. There were a number of marriages between these Hamburger children and their Barder cousins, children of Hannah and Louis. It seems that the children of Marcus’s first marriage remained in Paris with their mother’s family, though they were mentioned in his will.

Hamburger, the surname by which Leibel and his family was known from about 1805 onwards, probably suggests that his forebears came to Krakow from Hamburg, or even that one of them, perhaps as a merchant, visited Hamburg in living memory. There were many reasons why the Jews chose or were allocated surnames by their new rulers. Occupations were often the source as was the case with the Baders. Jacob, the earliest identified Bader, and Louis Barder’s grandfather, was a barber and attendant at the ritual bath house.  As happened in many societies he combined his skills as a barber with a role in minor surgery. The first sight of him is in the 1790 census, where he is listed as Jokel, barber and surgeon, aged 26, living in house number 85 with his 24 year-old wife, Leja. Also listed as living at number 85 in both the 1790 and the 1795 census was 40 year-old Filip Bonde, a doctor. Like Jokel, Filip was one of a select few in the 1795 census who were not identified by their father’s name in the patronymic column but, rather, with their occupation which in time led on to their surname. However, unlike Jokel, Filip already had a surname, Bonde, in 1790. An explanation is perhaps provided by the 1795 census where Filip, now spelt Feibel, is shown to have been born in Prag (Prague). From 1787, Jews living in the then Austrian Empire had been required to adopt surnames. Jokel, now identified as Jacob Bader, was still living at number 85, Judenstadt, for the 1795 census. House seems an inadequate translation for the dwellings which varied enormously in size. In 1790 there were 3 families, comprising fifteen people living in number 85. By 1795 the numbers of families had risen to 5 and the bodies to 18. Filip Bonde’s family, a wife, 2 sons and 2 servants accounted for 5 of the eighteen inhabitants of number 85 in 1795, and Jacob and his wife, Lea, with their one infant, made an additional three. Filip Bonde is listed as the owner of number 85 in successive lists of house-owners in 1797 and 1807. It was obviously a substantial dwelling, described as a ‘stone house in Hauptplatz’, comprising 337 square fathoms: some of the other houses were as small as 12 fathoms. Jacob himself appears as a house-owner in those two lists. He owned number 11 which covered 106 square fathoms but was described, like many others, as a ‘wooden building in bad condition’. In the 1795 census there were 6 families, eighteen people, living in number 11. Presumably Jacob drew rent from these tenants, supplementing his income as barber/surgeon. He himself did not live in number 11 in those years. His son, Herschel, or Hirsch, Louis’s father, was born in 1799 in house number 21, a brick house of 145 square fathoms, owned by Schachno Ascher. It seems that, by as early as 1797, all the house-owners had surnames, presumably for bureaucratic reasons. By 1805 a daughter, Malke, was born in house number 7, ‘an old wooden building in bad condition’ owned by Esaias Bleimann: also living in that building was a Joseph Bader, presumably a relation, a tax collector. However, Jacob and his family were living in the house he owned, number 11, when Hirsch married Zelda Goldbergowna in 1817.

As happened in many societies he combined his skills as a barber with a role in minor surgery. The first sight of him is in the 1790 census, where he is listed as Jokel, barber and surgeon, aged 26, living in house number 85 with his 24 year-old wife, Leja. Also listed as living at number 85 in both the 1790 and the 1795 census was 40 year-old Filip Bonde, a doctor. Like Jokel, Filip was one of a select few in the 1795 census who were not identified by their father’s name in the patronymic column but, rather, with their occupation which in time led on to their surname. However, unlike Jokel, Filip already had a surname, Bonde, in 1790. An explanation is perhaps provided by the 1795 census where Filip, now spelt Feibel, is shown to have been born in Prag (Prague). From 1787, Jews living in the then Austrian Empire had been required to adopt surnames. Jokel, now identified as Jacob Bader, was still living at number 85, Judenstadt, for the 1795 census. House seems an inadequate translation for the dwellings which varied enormously in size. In 1790 there were 3 families, comprising fifteen people living in number 85. By 1795 the numbers of families had risen to 5 and the bodies to 18. Filip Bonde’s family, a wife, 2 sons and 2 servants accounted for 5 of the eighteen inhabitants of number 85 in 1795, and Jacob and his wife, Lea, with their one infant, made an additional three. Filip Bonde is listed as the owner of number 85 in successive lists of house-owners in 1797 and 1807. It was obviously a substantial dwelling, described as a ‘stone house in Hauptplatz’, comprising 337 square fathoms: some of the other houses were as small as 12 fathoms. Jacob himself appears as a house-owner in those two lists. He owned number 11 which covered 106 square fathoms but was described, like many others, as a ‘wooden building in bad condition’. In the 1795 census there were 6 families, eighteen people, living in number 11. Presumably Jacob drew rent from these tenants, supplementing his income as barber/surgeon. He himself did not live in number 11 in those years. His son, Herschel, or Hirsch, Louis’s father, was born in 1799 in house number 21, a brick house of 145 square fathoms, owned by Schachno Ascher. It seems that, by as early as 1797, all the house-owners had surnames, presumably for bureaucratic reasons. By 1805 a daughter, Malke, was born in house number 7, ‘an old wooden building in bad condition’ owned by Esaias Bleimann: also living in that building was a Joseph Bader, presumably a relation, a tax collector. However, Jacob and his family were living in the house he owned, number 11, when Hirsch married Zelda Goldbergowna in 1817.

Many of the above facts came from an internet site of enormous value to Krakow researchers. As well as the two censuses and the 1807 house-owners list (I can’t trace where I found the 1797 list!), Dan Hirschberg has collected a number of other records. He also has links to other records including 3 articles by George Alexander, born in Paris to a Krakow family, Krakow resident until 1925, Holocaust survivor, now a Professor in the USA. These articles portray the evocative history and culture of a large, settled and even prosperous Jewish population which was destroyed in a few short years. Anyone can learn from them and those who are descended from that community will mourn its loss. George Alexander kindly sent me information he had translated from a book by Mayer Balaban, published in Krakow in 1936 and available in the New York Public Library: ‘Historia Zydow w Krakowie ina Kazimerzu 1304-1868‘. I was also sent photocopies of some of the relevant Polish pages by a Manchester historian, Geoffrey Weisgard. According to George Alexander, Jacob was described by Mayer Balaban as a ‘felczer’, or in modern terms, a ‘barefoot doctor’. There are a number of other references to Jacob Bader in Balaban’s work. For example, in 1832 during a cholera epidemic, Jacob, a surgeon assistant in the isolation hospital, was paid 400 zlotys for his help in cupping and applying leeches to the sick. There is also a reference in 1809 to Jacob’s giving vaccinations against smallpox. In the pages of Balaban there are a number of mentions of Filip Bonde who seems to have been a considerable figure in the medical world of Krakow It is possible that Jacob’s career as a barber surgeon started as an assistant to his landlord the Prag -born Dr. Bonde.

Jacob with his various sources of income was presumably quite well-to-do in local terms, despite living in a wooden house in bad condition. Since he and Leah Lewkowicz seem to have had about 15 children, most of whom survived infancy, this was just as well. Leah, who died in 1836, had been born around 1866. Louis’s father, Hirsch, was born in March 1799 and married Zelda Golbergowna, the daughter of Aron Goldberg, a sub-inspector policeman and Kreindla Herzlowna, in November 1817. In another document, in fact the record of the 1828 birth of Nachem Lazar Bader, later to become known as Louis Barder, Aron Goldberg was described as a money lender. Records of births, deaths and marriages, once located and translated, provide much information because every statement seems to have required the presence of named witnesses. Hirsch was living with his parents at house number 11 when he married in 1817 and he and Zelda were living there in 1823 when one of their sons, Chil Elias, was born. The translated birth document describes Hirsch as a stall keeper. When Nachem Lazar was born in November 1828, their address was house number 44 and Hirsch’s occupation was peddler (presumably the same as stall-keeper). As already mentioned, Aron Goldberg, the maternal grandfather, was one witness to Hirsch’s report of his Nachem’s birth. The second witness was Kolburg, a hospital servant: perhaps a colleague of Jacob the felczer. Hirsch and Zelda produced about 9 children of whom seven survived infancy. (It is impossible to be exact about such facts when so much depends on matching records and keeping track of name variations.) Of these, only Nachem and a younger brother, Aron Samuel, born around 1836, migrated from Krakow.

It is possible that the circumstances of Izrael’s birth in 1852 prompted Nachem and Haile Hamburger to leave Krakow, perhaps inspired by her brother Marcus (Menasses), who by then had been living in Paris for some years. They were certainly in London by 1854 when Levy, their first UK-born child and Harry Barder’s father was born. Although much of our early information about Levy is found in Manchester records, he was born in Spitalfields, London around 1854. He is not listed in the civil register of births deaths and marriages but this is the information he gave in successive censuses. It is likely that Louis and Hannah Barder soon after their arrival in England from Krakow had not got the hang of the registration system when Levy was born and anyway, birth registration became compulsory only in 1874. Unfortunately Levy is also missing from the registers of the Great, New and Hambro synagogues, the relevant ones for Spitalfields. The first child whom Louis and Hannah registered in England was Jacob, later known as Jack, who was born at 27 Duke Street, Old Artillery Ground, Whitechapel, in February 1856. Jacob’s father was named as Lewis, a tassel-maker, and his mother as Anne, formerly Hamburger. We have to rely on the information Isaac and Levy gave the census enumerators to establish their birthplaces, but we have a General Register Office certificate for the 1856 Whitechapel birth of their younger brother, Jacob. For the first time, the Louis Barders are officially documented in England. Like many people of all religions and backgrounds in nineteenth-century England, Louis and Hannah were less zealous about registering the births of their daughters than those of their sons. Nevertheless, from the birth of Jacob onwards, a succession of birth, death and marriage certificates, and census entries, gives us an idea of the numerous enterprises undertaken by Louis and his sons as they worked to establish themselves and their families in Victorian England.

When Izrael Barder was born in Krakow in 1852, Louis was described as a haberdasher, but his first recorded occupation in England, as the father of his new-born son, Jacob, was that of tassel-maker. “Master tassel-maker”, “trimming weaver”, “fancy trimming manufacturer” are his various descriptions on a series of birth certificates in the 1850s and ’60s. Prayer shawls, worn as an undergarment by devout Jews, were apparently finished with long tassels at each corner: perhaps Louis’s tassels were made for that purpose. The first census appearance of the Louis Barder family was in 1871. They were living at 3 Wilkes Street, Spitalfields, then the centre of London Jewry, now the heart of Banglatown. Louis and Isaac (the anglicized version of Krakow- born Israel’s name), were described as silk weavers, although by then silk weaving was a dying industry. When Levy married in 1875, Louis (or Eleazer as he is named on the marriage certificate) was designated a merchant, like Abraham, Rebecca’s father. By 1880, when Jacob, a warehouseman, married Rose White in Manchester, Louis was described as a furrier, but he had reverted to being a fancy trimming manufacturer in his 1881 census listing at King Edward Road, Hackney and was still so described on the 1891 census when he was living at 40 Horton Road, Hackney. By the time of Hannah’s death in Horton Road in 1898, and in the 1901 census, he was once again listed as a furrier. When he himself died in 1906 he was living at 111 Brondesbury Villas, with his son, Levy, a furrier.

Louis and Hannah were survived by ten children in England. The births of Isaac, Levy and Jacob, or Jack, have already been mentioned. Their first daughter, Betsy, was born around 1858. Aaron, known as Arnold, was born in 1859, Philip in 1861, Albert in 1864, Esther in 1865, Samuel in 1867, and Sarah in 1870. Unlike poor Rebecca Waxman and her mother, Hannah Barder did not have to endure the repeated tragedies of infant deaths. Just two of her many pregnancies are recorded as ending in death. Louis registered the birth on 21 August 1860 of Leah Barder on 6 September 1860. However, synagogue records show that Leah Barder was born in July 1860 but died and was buried on 4 September 1860. Presumably Louis’s attempts to register both the birth and death of his daughter were misunderstood by the local registrar. The death of another Leah, the 2-year-old daughter of Louis, a trimming weaver of 4 Turk Street, was registered in February 1865. Albert’s 1864 birth at 6 Fashion Street, Spitalfields, seems to have been the cause of another muddle between Louis and the registrar. Albert was registered as a girl named Alice: only 28 years later, in March 1892, was his certificate changed following a statutory declaration by Louis and Jacob Barder.

Krakow connections [1]

The steady growth of this large family not only helps to chart the progress of the Barders in England but also hints at the circumstances of their Polish background. Their son, Philip, applied for naturalisation in 1902. His naturalisation papers showed that he was born to Louis and Hannah in Krakow in August 1861, five years after the birth of Jacob in Whitechapel. The Krakow archives duly produced a record of the birth of Fischel to Lazar and Chaje Bader in 1861. Moreover, an 1857 Krakow register of inhabitants listed Lasar (Louis), born 1827, and Aron Samuel, born 1836, among the sons living with their father Hirsch Bader [sic], a factor (apparently meaning a middleman or agent, like Leibel Hamburger, Hannah’s father who took “the fruit of love” to the synagogue authorities). A later, possibly 1880, Krakow register lists Samuel, but not Louis, in Hirsch’s household. It might be that Louis and Hannah returned to Krakow for family comfort after the sadness of Leah’s birth and death in 1860. Perhaps Louis’s visit in 1857, between the births of Jacob and Betsy, was to encourage his younger brother, Samuel, to come to England.

The steady growth of this large family not only helps to chart the progress of the Barders in England but also hints at the circumstances of their Polish background. Their son, Philip, applied for naturalisation in 1902. His naturalisation papers showed that he was born to Louis and Hannah in Krakow in August 1861, five years after the birth of Jacob in Whitechapel. The Krakow archives duly produced a record of the birth of Fischel to Lazar and Chaje Bader in 1861. Moreover, an 1857 Krakow register of inhabitants listed Lasar (Louis), born 1827, and Aron Samuel, born 1836, among the sons living with their father Hirsch Bader [sic], a factor (apparently meaning a middleman or agent, like Leibel Hamburger, Hannah’s father who took “the fruit of love” to the synagogue authorities). A later, possibly 1880, Krakow register lists Samuel, but not Louis, in Hirsch’s household. It might be that Louis and Hannah returned to Krakow for family comfort after the sadness of Leah’s birth and death in 1860. Perhaps Louis’s visit in 1857, between the births of Jacob and Betsy, was to encourage his younger brother, Samuel, to come to England.

In the 1861 census Samuel Bardo, a 24-year-old fancy trimming manufacturer, born in Krakow, Austria, was living at 6, Pelham Street, Mile End. It was at this address that Leah was born and died in 1860 but Louis and Hannah were not there for the census and we now know that they were back in Krakow in 1861. In 1867, Samuel Bardo, of 3 Victoria Park Square, son of Hirsch Bardo, married Lydia Cohen, daughter of Isaac, a metals dealer, and in December of that year they had a daughter, yet another Leah, at 111 Grafton Street, Mile End. It had been a Lydia Barder who in 1865 reported the death of Louis’s two-year-old daughter: perhaps this was Lydia Cohen and once more a registrar was confused by the Barder family and their relatives. We lose sight of Samuel after his marriage in 1867, except for the mention of him in the undated Krakow list of inhabitants, back with his parents in Krakow. For some time, however, he was certainly in London, sharing an occupation and, in Pelham Street, accommodation, with his older brother. Although Samuel and Lydia disappear from British records, their daughter, Leah, is registered in the 1881 London census, living with her grandparents, Isaac and Louisa, at 3 Widegate Street, St Botolph’s Bishopsgate. Isaac was a rag merchant.

The links maintained with family in Krakow suggest that Louis and Hannah had more resources and more choice in their place of residence than most nineteenth-century Jewish migrants to Britain and the USA, or than impoverished migrants such as Abraham Waxman, escaping the repressive régime of Tsarist Russia. Whatever her comparative prosperity, however, Hannah had to cope with at least twelve full-term pregnancies in eighteen years, and constant moves with an increasing number of small children: and, above all, she had to adapt herself to a new country and a new culture. In the Barder saga it is inevitable that the story of the men, who carried a traceable name, should predominate, but it was Hannah who reared them.

Rebecca, Levy and the other UK-born Barders in Manchester

After the misfortunes and tragedies of their early married life in London, Levy and Rebecca returned to Manchester. Presumably Levy’s ventures as a furrier had foundered but the Barder family were not giving up on that for ever. Meanwhile, however, all the working-age young Barders were trying their luck in Manchester. Even Louis and Hannah must have been there at some stage because Sarah, their youngest child, only one year-old in the 1871 census was always said to have been born in Manchester, or sometimes, Cheetham. Unfortunately her birth was not registered. There was a large, well-established, Jewish community in Manchester, which had grown with the city and many of its members both shared and contributed to the prosperity of the city. They were somewhat nervous of the large-scale immigration of persecuted and needy Jews from Eastern Europe which began to occur from the 1880s onwards, but in the 1870s the Barders seem to have found accommodation in respectable areas and opportunities for business. In fact Levy and Jacob are the first ones to be recorded in Manchester. In the 1871 census, although Louis and Hannah listed their sons as living with them in Wilkes Street, the two young men, aged seventeen and fifteen, were also recorded in the 1871 census as lodgers in a household headed by a leather cutter, born in Russia. The illegible address seems to suggest that the dwelling was a cellar, like many other homes in that area. The boys gave their occupation as ‘traveller’, perhaps akin to ‘peddler’. like their grandfather as a young man.

Rebecca, of course, was born in Manchester and that was where she and Levy had married in 1875 but Isaac, the Krakow-born oldest of the Barder sons, had asserted his seniority by being the first to marry. In 1874, also in Manchester, he had married Charlotte Morris, in her home, 33 Clarence Street, Cheetham. Her father, Marks Morris was stated to be a ‘shochet‘, or ritual slaughterer. In fact in 1878 he was summoned for ill-treating a bullock. According to a report in the Jewish Chronicle, The prosecution said “the defendants were three English journeymen butchers and Marks Morris who held some semi-ecclesiastical office in connection with a Jewish synagogue and whose duties consisted amongst other things of taking part in the killing of such animals as were killed for the use of certain Jewish persons in the city of Manchester”. The summons was dismissed because there was no intention of cruelty – just a matter of custom. In later documents Marks was listed as a Reader in the Synagogue. Having moved to Manchester, presumably after the 1871 census when he was an apprentice silk weaver in Spitalfields, Isaac remained there for the rest of his life, apparently a stalwart member of the observing Jewish community. His daughter, Florence, born in Manchester in 1885, was interviewed in 1977 for a Manchester Jewish Oral History project. Most of the interview dealt with her experiences as a teacher in Jewish schools. When she was asked about her parents she had little more information to give than her cousin Harry passed on to his family. She mentioned her father’s brothers who all spoke Yiddish as well as English. She confirmed that her father had been born in Austria but said she thought that the city was Breslau. “Where is that?” she said. Breslau, historically the Polish city, Wroclaw, was under German rule for centuries and returned to Poland only in 1945. Florence knew that her mother had been born in Germany but had no idea exactly where. The 1901 census shows that it was in fact Florence’s mother, Charlotte Morris, who was born in German Breslau. Isaac from Krakow became a Manchester man and he died there in February 1927. In the 1895 Manchester Post Office Directory he was listed as a manufacturer’s agent with a business at 41 Swan Street and a residence in 41 Elizabeth Street. One of his sons, Herman, known, according to Florence, as Harry, went to South Africa. Another, Sam, became a Hatton Garden jeweller, in partnership with his sons, Victor Montague Barder and Norman Howard Barder, and with Laurence Moss, whose ancestry included German Jews settled earlier in Jersey, and whose family language at home in Harrow Weald was Channel Island French patois, rather than Yiddish or English! This partnership seems to have operated between London and Paris from before the First World War until after the Second World War.

Another Manchester marriage was that of Jacob who married Rose White in 294, Oxford Road, Chorlton in 1880. His address was 17 Carnavon Road, Cheetham. Jacob gave his occupation as warehouseman on his marriage certificate. Whether or not he had remained in Manchester since the 1871 census when he was slumming it with Levy he was still there beyond his 1880 marriage. He appears in the 1881 census at Cecily Terrace, Moss Lane East, Manchester. He was a Fancy Goods Textile Dealer and he and Rose, as yet without children, employed one servant. By 1893, however, he was back in London and was listed as a furrier at 30 Edgware Road.

Rebecca and Levy in the 1881 census were living at Dutton Street, Cheetham and the sadness of Bethnal Green days had passed. Levy was listed as a commercial traveller. They had a 2-year-old Manchester-born daughter, Hannah, known in the family as Dolly, and a young Irish servant, Annie Ward. Isaac and Levy were both listed in the 1881 Trades Directory for Manchester: Isaac as a waterproof goods dealer and Levy as a fancy goods importer. Levy’s business address in 1881 was 17 Carnavon Road, which had been Jacob’s address when he married in 1880. There was yet another fancy goods import business at Tib Street, Manchester and registered to L Barder. This could have been either Levy or his father, Louis. The 1881 census shows Levy’s brother Isaac, and his German-born wife, Charlotte, with three children and one servant at 17 Bent Street, Cheetham. (The one servant employed in all the Barder households perhaps results from the need of Orthodox households for non-Jewish help on Holy Days.) In 1882 Rebecca and Levy had another healthy daughter, Leah.

Moving on from Manchester

Their next child was Harry, born in Hull in 1883. Unfortunately the records of the Hull Synagogue were destroyed in the bombing raids of World War II so there is no hope of finding any record of Barder participation in the Jewish community there. Levy Barder is listed in the Hull Trade Directory of 1885 as running a fancy goods warehouse at 46 Whitefriargate, the main shopping thoroughfare of the town. He was not listed in the 1882 directory, nor in that of 1888. Number 46 looks a substantial building on the 1891 Ordnance Survey map of Hull. The port of Hull had become a major staging post for European migrants from Europe to the USA after the completion of a railway line which created a direct link between Hull, via Leeds, and Manchester to Liverpool and the emigrant ships to the USA. It is possible that Hull was at the same time a useful port for imports from Europe via Hamburg and that Levy and his brothers had therefore decided to open a warehouse there. Rebecca’s short stay in Hull might have been eased by contact with Waxman relatives. Jane Waxman was one of the few Waxman births registered anywhere in the country in the 1850s. She was born in Hull in 1857 to Samuel Waxman. Like Abraham, Samuel made his mark when registering the birth, possibly not a sign of illiteracy but merely that they were both more familiar with the Russian Cyrillic alphabet, rather than the Western European Roman alphabet. It is tempting to speculate that Samuel and Abraham were brothers, but all this is conjecture. Harry Barder never ventured any explanation for his Yorkshire birth, although in later years it qualified him to be President of the Yorkshire Society in Bristol.

By 1885, Levy and Rebecca were back in London, but in happier circumstances than those of their first stay. In December of that year, Celia, who grew up to marry Herbert Hess, brother of the more famous Myra, was born in Sidmouth Street, Hackney: Levy was still importing fancy goods. By the time of the 1891 census they had moved to 309 Edgware Road and Levy was a retail ironmonger. Kenneth Charles, the youngest of Levy and Rebecca’s children, was born at this address in 1893 and Levy then gave his occupation as furnishing ironmonger. Levy’s younger brother, Arnold, was also listed as an ironmonger in the 1891 census and as a furnishing ironmonger when his daughter, Amy, was born in 1890. Arnold and his family were then living in Chapel Street, which runs into Edgware Road, but the brothers were not running a joint business. The 1897 Post Office Directory shows Arnold’s ironmongery at 26 Chapel Street and Levy’s at 182 Edgware Road. Arnold’s and Levy’s families became closely and confusingly intertwined in later years. In 1885, at the North London Synagogue, Arnold married his cousin, Sophie Hamburger, daughter of Hannah’s brother Marcus (Menasses). Years later, in 1907, Harry married Sophie’s sister, Theresa Rachel,(known as Jimmie), as his first wife, while Dolly married Gustave, brother to Sophie andTheresa. (Arnold was thus both uncle and brother-in-law to Harry and Dolly!) Levy and Rebecca had two more moves that we know about. When Louis Barder died in 1906 he was living with Levy, a master furrier, at 111, Brondesbury Villas; and, as we have seen, Rebecca was living at Inglewood Mansions when she died.

The Barders as furriers

Alison Adburgham in her book Shops and Shopping 1800-1914 (Allan and Unwin, 1964), wrote:

The most prolific family in the fur trade must surely be the Barder family. Louis Barder, a mid-nineteenth century furrier, had seven sons who all became furriers. Instead of working in their father’s business, each one set up on his own. Thus they all became deadly rivals in business, although it was a devoted family in every other way.

All the brothers chose grand titles for their companies. The one which is still known today is the National Fur Company, which Arnold Barder established in Sloane Street in 1878, and moved to Brompton Road shortly afterwards. By the mid-1920s, only two other Barder brothers were still in the fur trade, their companies being the London Fur Company and one trading in Bristol. In 1926, the London Fur Company was bought by Swears and Wells, and by 1945 the Bristol company was also sold. But the National Fur Company went from strength to strength, and expanded into a concern with seven branches, four of them in Wales. The great grandsons of the original Louis Barder now run the business. The main shop is still in Brompton Road, and there are branches in Leicester, Cardiff, Swansea, Newport, Carmatharthen, Birmingham and Exeter. It is the only retail fur business on this scale to remain under private ownership.

It would almost seem that the Barder family must have appropriated all possible imposing titles for a fur business: yet the International Fur Store of 163 and 165 Regent Street was nothing to do with the Barders. It was established in 1882, under the management of Mr T.S.Jay, maybe a descendant of W.C. Jay. founder of Jay’s general Mourning Warehouse.

I too was convinced that the International Fur Store must have been a Barder enterprise. Alison Adburgham overlooked Jacob’s Universal Fur Company and I felt that the progression from London to National to Universal would not have skipped International! However 1882 was probably a bit early for any of the Barders to occupy premises in Regent Street. Sam was the only one to operate in Regent Street. He was listed at 302 Regent Street and 55 Brompton Road in 1909, and 288 Regent Street in 1914. But Sam never went in for grandiose names.

The fur trade eventually provided a living for all Louis’s sons (except Isaac the Manchester man), and for many of his grandsons, but all of them pursued other occupations before they became fully established.

The first recorded mention of any of the Barders as furriers appears as Levy’s occupation on the sad birth certificates of his three babies who survived for just a few hours in Hackney and Bethnal Green in 1876, 1877 and 1878. Levy, as already mentioned, returned to Manchester and to the import of fancy trimming. In 1881, Albert, then aged 17 and living with his parents in King Edward Road, Hackney, was a young furrier, although nine years later in 1890 he was living with his brother Isaac in Manchester and listed in the Trade Directory as an importer in Thomas Street. By 1891, when his first child, Ruby Rebecca, was born, he was a master furrier at 26 College Green, Bristol. Only 27, he was living in some comfort: the 1891 census, taken just before Ruby’s birth, shows Albert and Esther (formerly Moses), his 21-year-old wife, with a 60-year-old housekeeper and a nurse, presumably awaiting the arrival of the baby. (It was a year after Ruby’s birth that Albert, registered as Alice after his 1864 birth in Fashion Street, Spitalfields, finally gained his proper identity when his birth certificate was changed.) By 1897 he was listed in the London Post Office Directory as Albert Barder & Co., furriers, 30 Edgware Road, and was so listed for some years. Arnold, aged 25, was a furrier when he married Sophie Hamburger at the North London Synagogue in 1885, and so was Louis, father of the bridegroom. But we have seen that after his marriage Arnold, the later founder of the National Fur Company, seems to have maintained an ironmongery in 26 Chapel Street which had originally served him as both family home and workplace, even after his fur business was already in existence. In the 1897 Post Office Directory Arnold was listed both as a furrier at 37, St George’s Place, SW1 and as an ironmonger at 26 Chapel Street. In the 1913 Post Office Directory, Arnold Barder had acquired an otherwise unknown Henry James Hopper as a partner in ironmongery at 26, Chapel Street. Jacob’s wife, Mrs Rose Barder, is listed in the 1899 Post Office Directory as a wholesale manufacturing furrier at 145 Cheapside and in the 1897 and 1899 Directories a Barder & Co. wholesale fur manufacturers is listed, first at 28 Aldersgate Street and then at 12 Noble Street. When Jacob, or Jack, died in Hampstead in 1922 he left the Universal Fur Company of William Street, Knightsbridge to his son Leon. He in turn left the Fur Renovating Company of 58 Cheapside to his ‘dear wife, Fay’, when he died in 1938. Harold, Jack’s younger son, was also a prosperous furrier.

In the 1881 census Philip, a 19-year-old still living at home, was listed as a music master, the only non-commercial activity revealed by any of those first-generation Barders. Between 1883 and 1888 he had 10 ‘popular’ songs published, listed in the British Library with titles such as I wink at the girls on the sly and All because he saw me out with Sarah. The latter is dedicated to S. Pearl and I have found a Sarah Pearl in the 1881 census, a dressmaker, daughter of a widow with a young music salesman, James Murray as a lodger. Could Philip Barder possibly have met Sarah through James, one wonders? Whatever! In 1889 Philip married Susannah Sherman and in the 1891 census he was a fancy goods shopkeeper. Later, when he made his naturalisation application in 1902 he was a furrier, trading at 1, Oxford Street and 58 Baker Street: the 1903 Post Office Directory shows that his business name was The London Fur Company. This, according to Alison Adburgham, was the company bought by Swears and Wells in 1926, five years after Philip’s death. Samuel, the youngest of Louis’s sons and living with his parents in Horton Road, was listed as a furrier in the 1891 census, and was so described in 1900 when he married Henriette Cohen, daughter of Russian-born Myer Cohen, of Sunderland, at the Dalston Synagogue. Louis Barder, on Samuel’s marriage certificate, is described as a ‘Gentleman’. The 1901 census shows Louis still in Horton Road, aged 74 and a ‘Furrier on own account’. When Louis died in 1906, the Jewish Chronicle death notice of the immigrant Polish Jewish tassel-maker who died an English gentleman listed the addresses of all his surviving children.

According to the 1906 death notice, the three married daughters were living in London, Isaac was still in Manchester and Samuel was the only other son living outside London. He was at 26 College Green, Bristol, Albert’s address in 1891 and Harry Barder’s business address for many years until his retirement after the second world war. Although Levy was a furrier for many years, we do not know the whereabouts of his business, or its name. Unlike his younger brothers, but like his father and like his older brother, Isaac, he did not leave a will which could have told us so much. Perhaps he worked with his brothers in the London, National and Universal Fur Companies. That there was co-operation between the brothers is shown by the fact that Jacob’s original fur company in 30 Edgware Road in 1893 is later seen as Albert’s company in 1897 while Jacob moved on to the Universal Fur Company and a wholesale business with his wife Rose. The College Green business passed from Albert, there for the 1891 census, to brother Samuel and then to nephew Harry in 1906 or 1907. As already mentioned, Samuel was back in London in 1909 with fur stores in Regent Street and Brompton Road. In 1913 he had a fur shop at 167 Kensington High Street, increasingly fashionable since the opening of Derry & Toms and Barkers. In 1914 he was listed at 288 Regent Street but by 1929 he was a furrier in Hull, Harry’s birthplace, and it was in Hull that Samuel died in 1947. His only son, Reginald Seymour Barder, had died sadly young in a sanatorium in 1929, leaving a pathetic estate of £33 to his father, a furrier in Hull. Any idea that Harry, Samuel’s nephew and the last owner of the College Green shop which had passed through Barder hands since at least 1891, had somehow become a substitute son is disproved by Samuel’s will which names Betsy’s daughter, Celia Goring, not only as the sole beneficiary, but “a little mysteriously” as someone “who knew the wishes I have made known to her during my lifetime.”

Levy’s sisters

At the time of his death, Louis was living with Levy, his oldest London-based son. He had possibly moved there once all his daughters were married. The oldest daughter, Betsy, had been only about 20 when she married Solomon Schonman in 1878. She and her 2-year-old daughter, Celina, are listed in the 1881 census at her parents’s address, and she was working as a trimming maker, which suggests some financial problems. There is just one Schonman family indexed in the 1881 London census. Jacob Schonman, a watch-maker with his wife and five daughters, all born in Poland, lived in a very overcrowded house in Leman Street. Whether or not Solomon was part of that family, he was not in London for the census, but he and Betsy eventually produced three children and had a separate establishment by 1906. Unlike her sister, Esther waited until she was 35 before she married in 1900. In the 1881 and 1891 censuses she is listed as a milliner. Her husband was Isaac Philip Fainlight who appears in the 1881 census as a 7-year-old living in Newcastle Place, Whitechapel with his Polish-born parents and grandparents. His father was a tailor’s machinist. Esther only admitted to being 29 on her marriage certificate: but even so she was older than the 25-year-old Philip. Their son Leslie, in New York, married a Jewish girl taken to the US by her Russian parents. Leslie’s daughter, the poet Ruth Fainlight, found her way back to Europe and marriage to Alan Sillitoe, the writer. Sarah, the youngest daughter, unlike her older sisters, did not have an occupation on the 1891 census. This could reflect an increasing prosperity in the family, or else a role as helper to Hannah who by 1891 had lived for 66 hard years. In the 1901 census, after her mother’s death, she was still living with her father but she was earning a living as a ‘draper’s saleswoman’. In 1902, aged about 31, she married Abraham Sherman: her brother, Philip, had married Susan, one of Abraham’s sisters, in 1889 and there are marriages between Barders and Shermans in the next generations. The Sherman parents were Jacob and Sara, born in Austria and Holland respectively. Jacob, according to the 1881 census, was a jeweller and the family, with seven children all born in London, lived in Tredegar Square, Mile End, an address suggesting rather more prosperity than the Schonmans enjoyed. Jacob’s sister, Fanny Sherman, born in Austria, lived with them and worked as fur sewer (ie someone who sews!), a possible link with the Barder furriers. Similarly, Isaac Philip Fainlight’s grandmother, Juspa, was also a “furskin sewer” in 1881.

Harry was 24 years old when he married his 45-year-old second cousin, Theresa Rachel Hamburger, on Christmas Day 1907 in the Bristol Register Office. There was family opposition to the marriage because of the age difference. The unworthy suspicion that he married her for her money is not supported by her father’s will: when Marcus Hamburger died in 1881 he left an estate of under £2,000 to be divided between eight children, hardly a large fortune even in those days. Perhaps the family also disapproved of the secular wedding: there is a certain eccentric defiance about the choice of date and venue. (However, I have recently discovered that Harry, ever cautious, also married Theresa in a Bristol Synagogue on 19 January 1908, though he always kept quiet about that.) Levy appears on both marriage certificates as father of the groom, a furrier, but he did not witness either wedding. The witnesses were Hannah Hamburger and Rebecca Hamburger, Harry’s mother, and his sister Hannah, known as Dolly, who had married Rachel’s brother, Gustave (always known as ‘Gus’ or ‘Gussie’), in 1901. Despite the hostility to their union, Harry and Jimmie, as she was generally called, had almost reached their silver wedding before she died in June 1932. They had no children but Harry, in the bitterness of the years following the breakdown of his short-lived second marriage to Brian’s mother Vivien, always claimed that he had been idyllically happy with his first wife.

The Hamburgers

The Hamburgers, as already shown, were closely intertwined with the Barders. Significantly, when Harry helped his granddaughter, Virginia, with an attempt at a family tree for a school project, he started with the Hamburgers, the side of the family he shared with his first wife. Marcus Hamburger died in 1881, before Harry was born, and Harry didn’s t remember his name, but he knew that the brother of his grandmother, Hannah Barder, had married a Mlle. de Remillie and that these two were the parents of Theresa. Marcus and his wife Emilia Hamburger first appear in UK records in the 1861 census, living as lodgers at 26 Brydges Street, Covent Garden. They must have been very recent arrivals from France, and there is no trace of Arthur, Eugene and Sophie, their three French-born children. Perhaps they had been left in France until Marcus had found proper accommodation or perhaps their landlord didn’t think to list them in the household. Only recently has Brian’s cousin, Dick, descended from the marriage of Arnold Barder and Sophie Hamburger, been able to trace the background of Emilie Bouyn de Remilly, by concentrating on the name Bouyn. Emilie was born in Paris in about 1830. Her father, Antoine Francois Bouyn, descended from a family with distinguished military and medical histories. Antoine, born in Paris in 1793, worked as a civil servant in the Marine Ministry for some years but when he reported the death of his father in 1834, he had retired from the Ministry and was a jeweller, a professional link with Marcus. It is not easy to find birth death and marriage records in France, where they are lovingly guarded in their places of origin. Paris presents particular problems because records were largely destroyed during the Commune. Only with sworn testimony of a descendant with proof could records be reconstructed. This is how I found the record of Marcus’s first marriage to Jeanette Levy. Their daughter needed her mother’s marriage and death certificate for her own marriage and therefore a record was reconstructed which is now available in a record office. It was in fact a French Jewish genealogical society which traced this reconstructed record. I had asked them to look for a marriage between Marcus and Emilie Bouyn de Remilly. At first they claimed that this could not have a Jewish connection. I insisted that, whatever the names sounded like, since all their children were married in synagogues and both Marcus and Emilie were buried in Jewish cemeteries, they must have been Jewish. They then set to work and, to my surprise, came up with the certificate of marriage to Jeanette which, among other information, gave us definite proof of Marcus’s birth to Leibel in Krakow. But there is no marriage certificate for Emilie and Marcus, presumably because all her descendants are in England and have had no reason to seek reconstructions of her birth or marriage. Perhaps her mother was Jewish, thus making her Jewish. It is difficult to suggest a reason for Marcus and Emilie’s move to London. For want of any other explanation we must assume that Marcus saw good opportunities in London for a diamond merchant.

In that first 1861 census he was described as a dealer in precious stones. Harry’s wife, Theresa Rachel, was born at 16 Harpur Street, Bloomsbury, in December 1862, the first English-born child of Marcus and Emilie. Her father’s occupation is given on the certificate as ‘dealer in jewellery’. Although Marcus and Emilie were not in Harpur Street for the 1861 census the occupations of neighbouring householders and the numbers of servants they employed suggest that Marcus had already prospered before the Hamburgers moved to England. In the 1873 London Trade Directory Marcus was listed as dealer in precious stones and jewellers tools, a large stock of rough and painting enamels, French silver and copper foils, paint for stones, Vienna piercing saws, at 26 Woodbridge Square, Clerkenwell. Marcus died just before the 1881 census, leaving his business for his wife to carry on as long as she wished. He left £100 to Armand (Jeanette’s son) and £80 to Mathilde (their daughter). His schoolboy sons, Louis and Gustave, inherited half the residuary estate and the other half was to be divided among Sophie, Arthur, Eugene and Theresa. Emily, took over his diamond dealing business. She was living with her son, Eugene, also a diamond dealer, at 6 Wilmington Square, Clerkenwell, when she died in 1893.

In 1885, Sophie Hamburger, the French-born daughter of Marcus and Emily, married her cousin Arnold Barder at the North London Synagogue. He had been born at 20 Primrose Street, Bishopsgate in 1859 when his father, Louis was still working as a fancy trimming maker, but by the time of the wedding in 1885 both Arnold and Louis Barder were described as furriers. Arnold and Sophie had six children, one of whom, Herbert, called Bertie by the family, was apparently a great character and often remembered by Harry Barder even as late as the years when Jane, Brian’s wife (and the present writer), knew him. Bertie figured largely in Harry’s infrequent reminiscences about his family. Arnold’s National Fur Company, which appears in trade directories as early as 1907, was brought to the prominence its name demanded under Bertie’s management. Two of Sophie’s siblings married Levy’s offspring and thereby became in-laws as well as cousins. Harry married Sophie’s sister Theresa Rachel, aka Jimmie, and her brother, Gustave (‘Gus’ or ‘Gussie’), born in Clerkenwell around 1870, married Hannah, known as Dolly, in 1901.

Harry’s siblings and his own story

Dolly Hamburger, born Barder, spent some of her declining years with Harry in Bristol and Weston-Super-Mare before she died in the 1940s. Legend has it that Harry was frequently called upon to rescue Gussie, his two-times brother-in-law, from failed business ventures. Dolly and Gussie had just one child, Norman, a shy and artistic young man, killed during the second World War. Dolly also lived at other times with another sister, Celia, and her family, in Weston-Super-Mare. Celia, who had married Myra Hess’s brother, Herbert Hess, in 1916, had two sons, Peter and John. Peter Hess was later a local luminary as Mayor of Weston-Super-Mare. John was an enthusiastic activist in amateur dramatics, later a businessman and later still a professional chiropodist; his son, Nigel Hess, pursues a well regarded career as a composer and musician in a variety of media, including especially the theatre and television. Harry had two other siblings. Leah married Hyman Katzner, latterly called Hymie Kaye, in 1916, and Kenneth married Nancy Bick in 1920. Brian remembers occasional visits as a child to his aunt Leah and uncle Hymie in Brighton, and also long, wry, funny letters and the occasional much appreciated tip from Hymie. Harry seemed somehow envious of his much younger (and only) brother Kenneth, although what glamorous doings had prompted this envy we shall probably now never know.

The most comprehensive, though brief, account we have of Harry Barder’s early years appear in the War Office file of his First World War military service, held at the Public Records Office in Kew. He seems to have been conscripted during 1916 and served for nine months as a driver-mechanic at the RAF station in Manston, Kent. His home address at the time was Pembroke Hall, Clifton. He and Jimmie, his wife, had previously been living in Tyndall’s Avenue, Bristol for a number of years. Pembroke Hall was then a hotel[2] and it may be that Jimmie had decided to move there while her husband was away. It is his application for officer training which reveals something of his background. He firmly claims UK birth, not only for himself, but for Levy, his father. Although he always told Brian, his son, that he had been educated at the Jews’ Free School, he gave his place of education on this form as St Augustine’s , Kilburn (perhaps as an evening student after leaving the Free School?). He produced about a dozen impressive personal referees. One of these, the owner of a firm in Upper Thames Street, London, stated that he had known Harry Barder for many years, starting from when he had been an assistant in his father’s business in South Kensington. This is the only clue we have about Levy’s business and is another hint of a link with Samuel Barder, the only one of Levy’s brothers ever to be listed a Kensington furrier. Perhaps Levy and Samuel were partners both in Kensington and in Bristol before Harry took over the College Green shop after his marriage. Other referees included the deputy head of Clifton School (who noted that Mr Barder had continually placed his motor cars at the disposal of wounded soldiers), and prominent businessmen who praised his charitable and business activities. One of his major qualifications, however, was the fact that he had owned a motor-cycle and several motor cars since 1912 and had mechanical knowledge above that of most owner-drivers. He also stated that “about 15 years ago” he had served for four years in the 26th Middlesex Volunteer Regiment, presumably a territorial unit. This would have been about the time of the Boer War: he later told his son Brian that he had volunteered for the Boer War but had been rejected as too young. His 1917 application to be an equipment officer for the kite balloon section of the RNVR was turned down because there was no vacancy. He was eventually commissioned as a Mechanical Transport Officer with the RASC — on, of all days, 11 November 1918. He was demobbed in February 1919 and in January 1922, as a reserve officer, he was allowed to retain the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. More than 30 years later, his son Brian wore Harry’s old Sam Browne belt as a National Service 2nd Lieutenant in the 7th Royal Tank Regiment.

According to his own account, Harry was 13 when he left school and started work. Schooling must have been more intensive in those days: like my own parents, whose educational experience was similarly short, he had a literate, informed, inquiring mind. He was a founder member of the Bristol Club, rewarded in his old age with life membership, and a sometime President of the Yorkshire Society in Bristol. His fur shop at 26 College Green, much expanded after he had taken it over from his uncle to include new workshops and skilled staff, served the wealthy ladies of Bristol and its surrounding areas for many years and he provided well for his family and other dependants. Life in Tara, a green-roofed detached house in a leafy Bristol suburb which was the family home in the 1930s, was a model of middle class prosperity, with a chauffeur and a nanny to complete the picture. Nanny later became his housekeeper and he made sure that she was comfortably provided for when he died. He enjoyed the businessman’s pastimes of golf, card games with his friends, polite drinks parties. He read his Daily Telegraph every day and did its crossword, very quickly. He motored in France like any other 1930s prosperous Englishman, scornful of foreigners, and enjoying a sense of English superiority. He was an essentially middle-class English gentleman. And yet, anti-religious though he was, he could never bring himself to ignore the Jewish dietary prohibitions of his upbringing and he would always remark on the cleverness and artistic accomplishments of Jews when occasion arose. The conventional businessman retained the touch of a free-thinking outsider, who so many years before had given up attendance at synagogue as soon as he had had his bar mitzvah on turning 13, and had later cocked a snook at his own orthodox Jewish background and the middle-class gentility to which he not only aspired, but which he achieved, by marrying his middle-aged cousin in a secular ceremony on Christmas Day in a Register Office.

* * * * *

[1] We had some clues for the start of our search. Sophie Sherman, Philip Barder’s daughter, believed that the family originated in Krakow: we now realise that she was already 8 years old when Krakow-born Philip applied for naturalisation in 1902. An internet correspondent, living in Jerusalem and descended from Jacob and Leah through one of their daughters, has traced many of their other descendants. The families who stayed in Krakow died in Auschwitz and other camps. But Jacob’s genes survive in a widespread diaspora in Israel, New York and South Africa and the Bader name survives, only slightly disguised, in the descendants of Louis and Hannah.

[2] Information kindly provided by Jorgen Grabow Faxholm.

Jane Barder

London, April-October 1999; revised and up-dated, October 2005.

Is this family related to Harry Lewis, possibly Harry Levi

Brian writes: I’m afraid there’s no possible way of knowing!

Is the family who ran the National fur co. in 1950’s named Lyons related to the Barders?

Brian writes: I know very little about the National Fur Company beyond what is on my website about it, i.e. here. I have never heard of it having been run by a family called Lyons. Sorry.

Brian,

I am distantly related through marriage and came across the barders when researching the Coronel/Clements and Mendelsshons. Abraham was given 12 months for the crime of stealing a tin box abd £21 9s 1d. Let me know if you want a copy of that paper.

John

Brian writes: Thank you for this, John. My wife Jane writes:

Thank you very much for the offer of a copy of a paper about Abraham Waxman. By an amazing coincidence I printed out various newspaper accounts of Abraham Waxman’s crime, trial and imprisonment only yesterday. I was trying to use up credits in the British Newspaper archive before my 48 hours ran out and I tried looking for Abraham Waxman. I found that his exploits were published throughout the country! I had in fact bought a print-out of the statement of costs of his trial some years ago through Access2Archives but until yesterday I hadn’t discovered what he had actually done in June 1862. Poor Mrs Waxman would have been just getting over the March birth and death of their son. She herself died in 1865, leaving Brian’s grandmother, Rebecca Waxman, motherless at the age of ten.

As you will realise, the Coronels/Clements and Mendlessohns aren’t in our line of descent but I came across them some years ago when i was helping a Barder cousin, who is descended from Matilda Coronel. In fact I think there were two Coronel/Barder marriages. I was tempted to spend more time explorong the Coronels etc. They looked very interesting.

Can anyone connect me to the Barders of Bolney Hall in Sussex who rescued my father Hans Marcus from persecution in Germany in 1939

I have an obituary of your father given by mine, the latter is no longer with us, and he talked about your father and his fine abilities. My father was Alan, the younger son of HB.