US elections: second presidential debate

Two things in particular struck me as I watched all 90-odd minutes of the second US presidential debate between Senators McCain and Obama, held last night in Tennessee and available now on the Web (e.g.) here: first, the ever-widening gulf between political perceptions in (most of) the US and in (most of) Europe; and, secondly, the contrast in attitudes between the two candidates on the question of relations between America and the outside world.

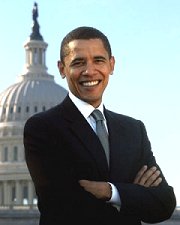

(1) If the two Senators were competing for European votes, it's a million to one that Barack Obama would be 20 to 30 percentage votes ahead of John McCain in the opinion polls, and heading for a landslide victory. The American electorate had the two candidates neck-and-neck, with McCain slightly ahead in some polls, until the global financial system imploded, and enough Americans blamed the Republican administration for the failure to give Obama a narrow lead. In some states and some polls Obama's lead is still so slim as to be statistically within the margin of error. Is this really just a question of style, with McCain's folksy populist boastful chauvinism going down well with millions of Americans when most Europeans find it merely embarrassing? Is it only style that makes so many Americans hostile to Obama because his sophisticated, nuanced, sometimes hesitant manner strikes them as élitist, remote, professorial, detached, while to most Europeans it suggests someone whose intellect makes him on the face of it well qualified for high political office? Can it seriously be the case that millions of Americans vote for the candidate with whom they would most like to go out for a beer, and not the one who seems best equipped by character, intellect, judgement and declared policies to lead the most powerful nation on earth? How has it come about that 'liberal' is a dirty word across great swaths of the United States?

Of course public opinion and assumptions in some parts of the US, mainly in the big cities on the east and west coasts, closely resemble those in Europe; there's a gulf within America too. But neither George W Bush nor Senator John McCain would ever, surely, have come within a mile of winning an election for President of the United States of Europe, let alone winning two elections in a row.

(2) How America sees itself in relation to the rest of the world emerged in the debate as a sharp point of difference between the two candidates. McCain spoke of the US as a huge force for peace in the world, as a peace-keeper and peace-maker that should be ready to use its military might to resolve problems wherever they arise in the world:

…the fact is, America is the greatest force for good in the history of the world. My friends, we have gone to all four corners of the Earth and shed American blood in defense, usually, of somebody else's freedom and our own. So we are peacemakers and we're peacekeepers. But the challenge is to know when the United States of American can beneficially affect the outcome of a crisis, when to go in and when not, when American military power is worth the expenditure of our most precious treasure, American blood. And that question can only be answered by someone with the knowledge and experience and the judgment, the judgment to know when our national security is not only at risk, but where the United States of America can make a difference in preventing genocide, in preventing the spread of terrorism, in doing the things that the United States has done, not always well, but we've done because we're a nation of good.

Obama, in contrast, stressed the need to restore America's damaged standing in the world and to repair its international alliances without which the US would be impotent to address global challenges:

Obama, in contrast, stressed the need to restore America's damaged standing in the world and to repair its international alliances without which the US would be impotent to address global challenges:

Senator McCain and I do agree, this is the greatest nation on earth. We are a force of good in the world. But there has never been a nation in the history of the world that saw its economy decline and maintained its military superiority. And the strains that have been placed on our alliances around the world and the respect that's been diminished over the last eight years has constrained us being able to act on something like the genocide in Darfur, because we don't have the resources or the allies to do everything that we should be doing. That's going to change when I'm president, but we can't change it unless we fundamentally change Senator McCain's and George Bush's foreign policy. It has not worked for America.

No prizes for guessing which of the two approaches comes closer to understanding and acknowledging the way the US has come to be seen in much of the outside world in the past eight years of the Bush administration. Statesmen as well as diplomats need to learn to understand how their governments and countries appear to others, both friends and especially adversaries, however unflattering the image.

Half of all American voters, according to one leading poll, are aware of international hostility to the Bush administration and its record, although the toddlers' nursery language of American pollsters' political discourse makes it impossible to make the vital distinction between hostility to the government and hostility to the country:

just 28% [of American voters] think other nations like America, according to a new Rasmussen Reports national telephone survey taken Sunday night. Half of voters (50%) say other nations dislike the United States.

One of the McCain team might usefully encourage the GOP candidate to read and heed the Scottish poet's To a Louse, which famously finishes:

O wad some Pow'r the giftie gie us

To see oursels as others see us

It wad frae monie a blunder free us

An' foolish notion…

Well, I suppose it could have been worse. It could have been Sarah Palin. If she's going to be a heart-beat away from the presidency, let's hope that John McCain's heart will go on beating strongly for at least four years — or eight, if the worst comes to the worst a second time.

PS Andrew Sullivan's running commentary on the debate (comments rather confusingly in reverse chronological order) is well worth reading, including his final classic conclusion:

This was, I think, a mauling: a devastating and possibly electorally fatal debate for McCain. Even on Russia, he sounded a little out of it. I’ve watched a lot of debates and participated in many. I love debate and was trained as a boy in the British system to be a debater. I debated dozens of times at Oxford. All I can say is that, simply on terms of substance, clarity, empathy, style and authority, this has not just been an Obama victory. It has been a wipe-out. It has been about as big a wipe-out as I can remember in a presidential debate. It reminds me of the 1992 Clinton-Perot-Bush debate. I don’t really see how the McCain campaign survives this.

Brian

Whilst I am in almost entire agreement, as a felow 'liberal' European, with your assessment of the positions adopted by the two Presidential candidates in yesterday's debate, I am suprised at your disappointment with the narrowness in the current opinion polls. Like you I have a daughter living in the States and according to her, the views held by middle america may be parochial but they reflect an assessment of character and a gut feeling as to whom they trust the most to protect their living standards rather than any great analysis of policy. If I am right, then I suspect that in practice this is remarkably similar to the motivation of most European electorates.Whether this is a good or a bad thing is a different issue; it is just the reality.

Brian writes: Jeremy, thanks for this. Of course there may also be additional and more complex factors at work here. Please see Tim Garton-Ash's article in today's Guardian about the "cultural civil war" in the US (here) and the even more revealing, brilliant, devastating, article about Sarah Palin by Jonathan Raban in the London Review of Books (here): essential reading especially for European observers of the American political scene and both full of suggestive material about what drives voters on the conservative side of the "cultural civil war" in the US. (I wonder whether the Raban article, which really takes Governor Palin apart, has been noticed or even reproduced in the US? It deserves to be!) But of course none of this affects the perfectly valid additional insight provided by your daughter.

The words that you quote from McCain could have have come directly, mutatis mutandis, from any Roman emperor defending the pax romana. But a) that wasn't as peaceful as it might have been (there were terrorists across the Rhine and in Judaea), and b) the Americans are not supposed to be imperialists.

Brian writes: An interesting point, Peter. A British political leader at the height of the days of empire might have spoken similarly, too:

Similarly the French and their mission civilisatrice — and no doubt the same lofty motives energised the Spanish, Portuguese, Persian and other empires, as well as the Roman and American.

Can I try to answer one of your questions, Brian? Thus: "Can it seriously be the case that millions of Americans vote for the candidate with whom they would most like to go out for a beer, and not the one who seems best equipped by character, intellect, judgement and declared policies …?"

Well, yes. It seems to me that this is one of the consequences of American egalitarianism, in contrast to what is left in the UK of a system of deference. Most Americans are brought up to believe that everyone is as good, in every possible way, as everyone else; anyone who pretends, or is held, to be better in one way or another than the herd, must be a fraud, a very suspect human being, not one of us. It happened to Adlai Stevenson, and if Obama escapes the same treatment (despite the additional burden of residual colour prejudice) it will be a miracle. (It is of course a miracle, to America's great credit, that he has got so far.)

The tall poppy syndrome is not, of course, unknown in the UK, but here it is more common for capable people to get their heads above the parapet first, before the media get down to the merciless business of chopping them off at the knees. We still retain a notion that those we appoint to high office should have some greater knowledge and understanding (and interest) than the average about economics, or global politics – or just how the world works. And we still retain some respect for those who have, and can convey, that knowledge understanding and interest, instead of insisting that they hide it under a cloak of pretend ordinariness.

The Sarah Palin phenomenon demonstrates this clearly: where McCain has to work very hard to seem averagely, acceptably, stupid, Palin has it from the outset; her mouthings are way beyond parody; her ignorance, her incoherence are those of Everyman/woman suddenly thrust into the international spotlight – and millions love her for it – not despite it, but for it.

Listening to this debate I am impressed by Obama's failure to join McCain in crawling in the populist gutter – most of the time. If he wins, by however small a margin, it will be the first sign that America is prepared to recognise and honour quality before self-identification.

Brian writes: Thanks for this, Robin. I think there's a lot in what you say. A friend of long standing (and of American origin, a long-time UK resident and dual citizen) has commented privately to me on this post that I shouldn't "get too carried away with European sophistication. Remember this is where the holocaust happened and more recently Jean Marie Le Pen was runner-up in a French Presidential election. And Mr Berlusconi has been re-elected in Italy" — a thought-provoking and worrying reaction. I have replied that I certainly didn't mean to imply that I regarded Europeans as in any way superior to Americans; quite the reverse, indeed, in many areas; and that I thought the UK and some other European countries much likelier than the US to experience an extreme right-wing, even fascist, backlash following the forthcoming years of slump (with high unemployment, widespread homelessness and falling living standards perhaps accompanied this time by high inflation, food and energy shortages, perhaps food and race riots, etc.) that we have to expect as a result of the melt-down of the global credit and banking system. New Labour will leave a legacy of illiberal, authoritarian legislation (accepted as being allegedly required in the context of the "war on terror") which could easily be exploited by a right-wing, chauvinist, anti-immigrant, anti-EU, protectionist, anti-human rights government carried into power on a wave of anger at the effects of the slump and a craving for the smack of firm government, encouraged by the Daily Mail and the Murdoch press, and probably welcomed by the bulk of the police and the military. Notwithstanding some of the illiberal excesses of the George W Bush years, such a development seems a lot less likely in the US, thanks to a much firmer American hold on personal freedoms and democracy as guaranteed by a liberal written constitution and safe-guarded by the dispersal of power among the 50 states. Europe in general, and the UK in particular, have nothing to be smug about when we contemplate the American political scene. Which British black politician has come even a quarter of the distance already travelled by Barack Obama? As you rightly say, Obama's success so far in overcoming the huge potential handicaps of being liberal, intellectual and black and having what sounds like an unAmerican, probably Muslim name, is hugely to the credit of the United States, even if in the end he is denied the ultimate prize of the Presidency because of the Bradley Effect or some catastrophic event occurring between now and 4 November, or both.

I should perhaps have put more emphasis in my post on the fact (which I did refer to) that the gulf in political perceptions and discourse between many Americans and many Europeans also exists within the US. There's a very relevant analysis of this "cultural civil war" within the US in today's Guardian by Timothy Garton-Ash (see http://bit.ly/2UtX8N). It's noteworthy that the conservative side in the American cultural civil war lumps the "secular-progressive" side in with the pesky Europeans, an identification which is obviously meant as the opposite of complimentary!

The candidates have a major difference in their leadership styles: McCain tends to say, "Follow me because the other guy can’t get it done" while Obama says, "Follow me because I can get it done." Ideally, the candidates should say, "Follow me because i will help you get it done" … in any case, of the two of them Obama demonstrates a better leadership mentality

Brian,

I'm really not sure that the differences between Obama and McCain are as large as they appear to be. There is a contrast in their use of rhetoric and between their styles, but what of the substance? I must admit I'm very cynical indeed about American politics. Obama is an attempt to re-brand the United States after the debacle of the Bush decade. Brand Bush succeeded domestically, but overseas he was a no-sell product. In relation to the main international conflicts the two candidates are very close indeed. Both swear undying loyalty to the Israeli cause. Both are hostile to Iran. Both are ready for more war in Eurasia. Obama seems eager to expand the war in Afghanistan into Pakistan, with potentially disastrous results. The consequences of destabilizing Pakistan don't bear thinking about! Both candidates are, seen from a European perspective, really conservatives, only one is marginally more 'liberal' than the other; how much choice that leaves the voter is arguable and perhaps a question of individual temperament.

Brian writes: Thanks, Michael. I think we have to accept that the positions of any realistic aspirants to high public office in the US are going to be more or less the same on certain core issues: no candidate would get anywhere, for example, by announcing that he or she didn't 'support' Israel. But within that headline position there's plenty of room for varying views — about the position of Jerusalem, the West Bank settlements, the return of Arab 'refugees', and so on. And I don't think Obama has talked about "expanding the war in Afghanistan into Pakistan": he says that if the US had Osama bin Laden in its sights in Afghanistan and the Pakistanis wouldn't do anything about it, he (Obama) would authorise an air attack to kill him, but clearly that isn't quite the same thing. And on many issues Obama and McCain are miles apart; so, it seems to me, are their respective political philosophies and values. There can't be any guarantee that Obama would be a magnificent success in office, but there's plenty of evidence that he wouldn't be anything like the disaster McCain would be, and at best he might turn the US around. Can you imagine Obama having the cynical irresponsibility to choose as his running-mate and candidate for Vice-President anyone as deeply objectionable and inadequate as Sarah Paling?

Brian,

I agree with a lot of what you say, but on the other hand… I respect your perspective and arguments, but… My problem is the ‘core issues’. I’m not sure that stripped of their differing rhetoric that the real differences between the two candidates are particularly substantive. During elections the rhetorical differences are emphasized, yet afterwards, things calm down, the ritual is over, and things seem to resort to business as usual. But then I don’t really think the US has a two party system at all, rather a one party system with two factions, rather like the Whigs and the Tories, or New Labour and the New Conservatives. I don’t actually believe they are miles apart on many issues, certainly not on foreign policy. There is a difference of emphasis, one wants to fight in Iraq, the other wants to fight in Afghanistan. Both of them have an appaling attitude to the conflict in the Middle East.

Obama’s policy towards Afghanistan is extremely dangerous as ‘winning’ in Afghanistan means expanding the war across the border into Pakistan with potentially disasterous results to follow.

I don’t believe Obama will turn the US around, this isn’t the way the American system works, unfortunately. I’d like to believe that a ‘good emperor’ had the super-human ability to reform and save an empire, but I don’t think history works quite like that.

Sarah Palin is, of course, a deeply objectionable choice, seen from a European perspective, yet in American terms choosing her was a stroke close to genius, especially if McCain wins! That seems unlikely. However, Sarah Palin reminds me of Ronald Reagan who was regarded with contempt by intellectuals and scorned, yet a few short years later was on his way to the Whitehouse. I think underestimating right-wing populists and what they symbolic qualities, many of them non-verbal, is understandable, but never-the-less, a mistake.

If I may develop your comment – though tangentially to the main point – the Spanish and Portuguese empires had no idea of spreading civilisation beyond the natural desire of the Catholic Church to convert heathen souls to Christianity. (That unquestionable role of the Church is, incidentally, what gives the lie to the oft-repeated allegation that the conquistadores set about the deliberate extermination of the indigenous population; on the contrary, the Church not only wanted to keep them alive as converts, but also opposed slavery – to start with anyway.) The main aim of the State, on the other hand, was to plunder the mineral resources, and exploit the natural and human resources, as comprehensively as possible.

However, it is often not appreciated that these earlier European empires were effectively medieval in nature: they lacked the cultural self-confidence of the Romans on one hand, and on the other the intellectual and cultural values of the Enlightenment, and the financial and physical resources of capitalist industrialisation, which underpinned the later British and French empires in their dealings with native populations.

I could also add that empires are often acquired more or less accidentally, by exploiting existing power vacuums (the Spaniards in Mexico and the Caribbean, the British in India), to ensure secure borders, or to support trading patterns (the flag following trade, be it noted). The one major part of the British Empire that was really forced was Rhodes’s notorious land-grab in Southern Africa; we know what that led to and it was not civilisation as we know it. Also, it is the blatant American imposition of itself in South Asia, the use of hard power alone, that is proving their nemesis as an imperial power.

Brian writes: Peter, many thanks for this penetrating comment. What you say rings very true. Much of the British African empire (although not including South Africa or Rhodesia/Zimbabwe) was certainly acquired, if not accidentally, then in the teeth of strident opposition from the Treasury in London, which feared that exercising responsibility for such huge tracts of land and for so many peoples would entail a hefty bill for the British taxpayer. Some of it was taken over to prevent the French (or other would-be European colonial powers including Italy, Germany, Portugal and Spain) getting it; some to establish reasonably stable conditions to allow profitable trading — not of course in slaves, since Britain had outlawed the slave trade in 1834; some — although never in West Africa — to provide a home for white British settlers. In the biggest country, Nigeria, the British Governor, Sir Frederick Lugard (later Lord Lugard) , insisted on banning or severely restricting Christian missionary activity, especially in the mainly Muslim north, which he saw as liable to stir up trouble; he insisted on working with and through local traditional rulers ('the dual mandate'), partly because it was cheaper, partly out of respect for local tradition and customs, although he banned some practices which even then struck Europeans as barbaric. Colonialism was always a complex and many-sided phenomenon which attracted saints and rogues in roughly equal numbers: and men — and especially "their" women — who got involved in it did so for a multitude of different reasons, many of them honourable and sometimes heroic.